Those who work along the U.S.-Mexico border say inefficient administration is making the number of asylum seekers, and their potential effect on the U.S., look scarier than it really is.

At some point in the past week, more than one U.S. government official felt justified in tear gassing asylum seekers. Such dramatic maneuvers are no doubt enabled by national fear that the country is being overrun. That fear, in turn, is stoked by news stories with staggering figures and dramatic images.

The truth of the situation may be more mundane: The asylum process is inefficient, and no one has an incentive to fix it. In fact, the resulting chaos has proved politically expedient for the Trump administration.

While Tijuana and California received most of the remaining asylum seekers in the heavily publicized “caravan,” cities all along the U.S.-Mexico border have seen smaller eruptions in the ongoing immigration disaster. Advocates working in those cities do not, however, say that they are seeing waves of immigrants, floods of asylum seekers, or any other crisis-invoking metaphor. The U.S. is not, they say, being overrun.

According to data from Homeland Security, the U.S. has granted asylum to more than 20,000 people per year for over a decade. While the number of applications has increased from its sharp drop in 2016, it picked back up with a trend that has been ongoing since 2013, according to a U.N. report. The U.S. has seen steadily increasing numbers of asylum seekers from Central America as violence in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador has intensified.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the issue is capacity.

“When our ports of entry reach capacity, CBP officers’ ability to manage all of their missions — counter-narcotics, national security, facilitation of lawful travel and trade — is challenged by the time and the space to process people that are arriving without documents,” a CBP spokesperson said. “From time to time we have to manage the queues and address that processing based on that capacity.”

Capacity can be exceeded in two ways: an unexpected increase in need, or a decrease in resources given to CBP to meet those needs. The spokesperson did not respond to Sojourners' questions as to what was causing current issues, but whatever it is continues to cause administrative backlogs and potentially dangerous situations in cities like Matamoros, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas.

Matamoros, Mexico

Early in October the Mexican government reached out to Casa Bugambilia, a medical shelter run by Methodist missionaries in the colonias outside Matamoros, Mexico. The shelter would be needed to house some of the 131 people waiting for their asylum claims to be processed. The U.S. had slowed it’s asylum applications processes, sometimes only seeing two per day.

Casa Bugambilia was built to hold 25 medically fragile patients and the several volunteers who would attend to them, including American Larry Cox and his Mexican wife Nancy Rodriguez-Cox.

The couple moved across the border into Los Fresnos, Texas, in 2011, but they continue to take volunteer groups across the border daily to work at Casa Bugambilia. Once refugees began to arrive on Oct. 21, the shelter quickly exceeded capacity, at one point holding 96 people, according to Larry Cox. In addition to local patients, Casa Bugambilia housed refugees from Cuba, Eritrea, Guinea, and Cameroon. Others from Central and South American countries were quickly sent to a neighboring shelter to provide relief to the overcrowded facility.

Other nearby shelters were also at capacity, leading Cox to ask what was behind the sudden influx. He learned that nothing had changed except the number of asylum seekers being allowed into the U.S. every day. CBP officers had moved up to the international line on the bridge, prohibiting anyone from crossing the bridge so as to claim asylum on U.S. soil. Instead, they were barred from entry until their name was called.

“By putting officers on the bridge, U.S. Customs and Border Protection is taking a proactive approach to ensure that arriving travelers have valid entry documents in order to expedite the processing of lawful travel,” the CBP spokesperson said.

For the immigrants, Cox explained, those most desperate to get in did not trust the government enough to wait for their assigned day in the relative safety of Casa Bugambilia. They went to the international bridge between Matamoros and Brownsville, Texas, camping out for days so as not to miss their chance. They had seen how the “list” they were on had proven fluid. If someone didn’t show, another could be chosen instead, plucked from the crowd at the bridge.

2018-11-01t204213z_1_lynxnpeea03ya_rtroptp_4_usa-immigration-mexico_1.jpg

“There are about 45 asylum seekers sleeping on the ground at the two downtown bridges, three of whom we know from their stays with us at our refuge and who still wait,” Cox wrote in an email to elected leaders, pleading for assistance.

Cox said one man in particular suffered from filariasis, a tropical disease causing rashes, and, if left untreated, blindness. On Thanksgiving day, Doctors Without Borders arrived at Casa Bugambilia to help the Coxes meet the growing medical needs. Several nurses from the African countries go regularly with Nancy Rodriguez-Cox to the bridge to clean bathrooms and other public spaces, fearing an outbreak of disease from unsanitary conditions.

While they waited, Cox had the refugees practice filling out the forms they would need to claim asylum. He didn’t want to see a technical glitch defeat these people he had grown to so respect.

“Those at our refuge are well-educated, industrious and— as one pastor who visited us put it— noble,” Cox wrote in an email.

He has reached out for more resources from the governments of both Mexico and the U.S. — administrative assistance, case workers, anyone who can help keep this bureaucratic crisis from worsening an already significant humanitarian one. Already, immigrants at Casa Bugambilia have been told to stay off the streets for their own safety, and not to upset the balance in the colonia, where the cartel is in almost total control, Cox said. The immigrants, he said, are in an ever tightening vice.

El Paso, Texas

Later in October, Catholic Charities received warning that 2,000 people would be released from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody in Tucson, Ariz., and dropped off at five shelters in El Paso, Texas. The shelters were all within the Archdiocese of El Paso.

Knowing that the El Paso shelters, each small and independently run, would not have the administrative coordination to handle the influx, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of San Antonio sent Executive Director Antonio Fernandez and a team of volunteers on the 12-hour drive west in “Hope,” CCOASA’s emergency supply truck.

They arrived to scene that Fernandez would describe as “busy,” he said, but not “overrun.” Because CCOASA serves a steady stream of immigrants released from detention centers around San Antonio, Fernandez and the volunteers were able to streamline much of the process in El Paso. Many cities, he said, have that infrastructure in place.

CCOASA itself recently purchased a small secondary shelter for just such an occasion, as they saw an increase in numbers beginning in September. They opted not to purchase a larger facility because, Fernandez said, with the inconsistency in the flow of people, it would have been a financial and safety liability. Between the shelters run by CCOASA and its partner organizations — San Antonio Mennonite Church, a local congregation of Latter-day Saints, the Interfaith Welcome Coalition, and the City of San Antonio — the city can easily house 100 people per night as they prepare for the next leg of their journey.

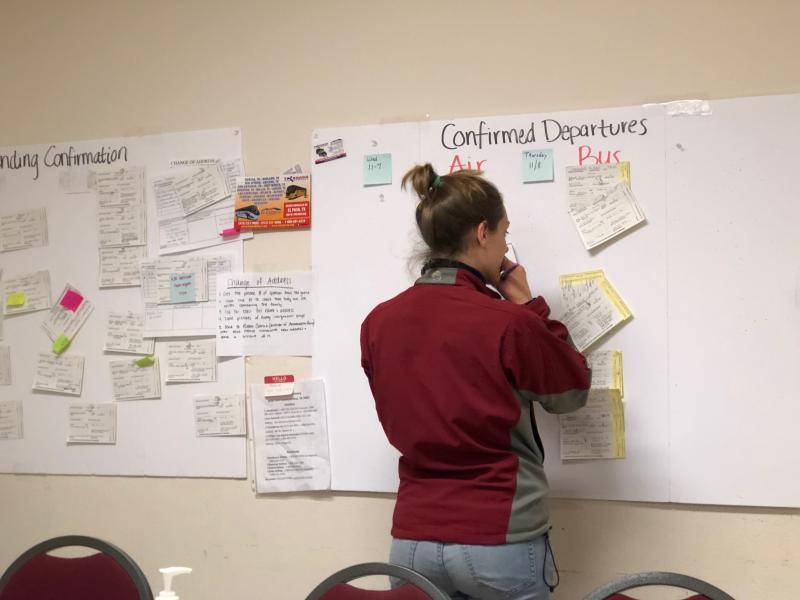

img_1911.jpeg

But typically when ICE releases people from detention, they have been in custody long enough to make contact with their stateside sponsor and possibly a lawyer or advocate. Most of those released from Tucson, Fernandez said, had been in the U.S. for less than one week. They arrived in El Paso disoriented, without U.S. contacts.

“I still prefer when they are released sooner than later,” Fernandez said. When they stay in the detention centers for too long, he explained, many come out sick and traumatized.

The potential for chaos in El Paso was indeed high, but a little administrative planning goes a long way, Fernandez explained. CCOSA still has crews of staff and volunteers rotating through El Paso, but he felt the situation was stable enough for him to return to San Antonio. It helped, too, that manufactured crises elsewhere meant the El Paso teams didn’t have to fight through a media circus making the issue seem more dire than it was.

Neither Cox nor Fernandez would muse as to the reason for CPB’s capacity problems, or comment on whether the government is trying to create the illusion that the country is being overrun, baiting the media to capture panic-inducing images.

They will only say that the administrative problems are solvable. We have the ability to process even the largest numbers of people with efficiency and dignity.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!