Robin, the comic book sidekick of Batman, has come out as queer in a storyline that many readers believe has been a long time coming. In establishing Tim Drake as queer in comics canon, the writers employ the mythic power of comics to make space for queer readers, echoing readings of biblical mythology by queer theologians.

Tim Drake has had an on-again, off-again relationship with Stephanie Brown (aka Spoiler), and at the conclusion to the “Tim Drake: Sum of Our Parts” story arc in Batman: Urban Legends #6, he agrees to a date with his friend Bernard.

On launch day, Meghan Fitzmartin, one of the writers for the issue (along with Joshua Williamson, Matthew Rosenberg, and Chip Zdarsky) tweeted, “My goal in writing has been and will always be to show just how much God loves you. You are so incredibly loved and important and seen…”

She told the BBC that she spent “a lot of time and a lot of prayer” making sure Robin’s coming out was respectful and wholesome — no mean feat when the Robin mantle has been the target of countless homophobic jokes over the decades.

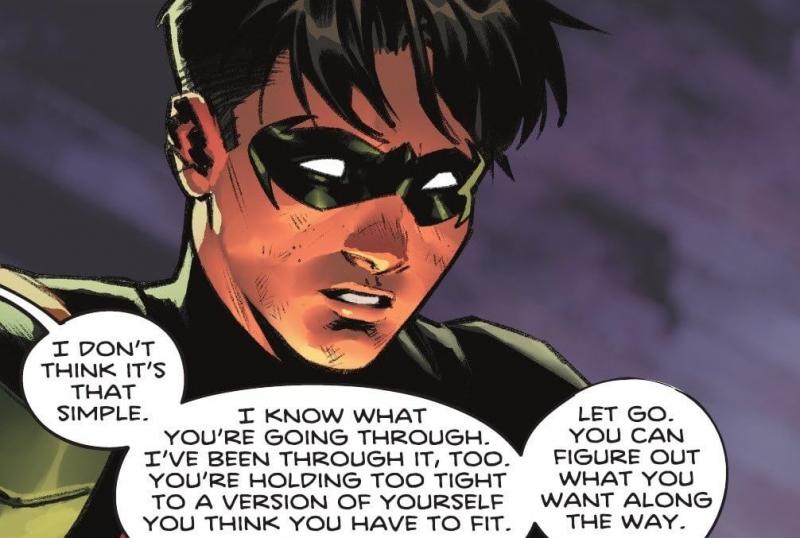

Above is a panel from Issue #6. After defeating the bad guy, Robin turned his attention to his inner demons. Robin has just realized he is attracted to Bernard, but is afraid to live into those feelings. A friend of Robin’s stands with him in the shadows. The friend tells Robin (whose expression is a powerful mixture of hope and fear, illustrated by Belen Ortega), “I know what you're going through. I've been through it, too. You're holding too tight to a version of yourself you think you have to fit. Let go. You can figure out what you want along the way.”

You may be wondering: Why all this fuss about a comic book? After all, aren't these just cartoons for kids? While that was certainly comics’ origin story, the reality is much more complicated. Comic books function as our contemporary mythologies. They help us talk about who we are, who we aspire to be, and how we relate to one another. It’s no accident that the superhero resurgence began with Sam Rami’s Spider-Man film, which premiered less than 9 months after 9/11. Superheroes not only help us feel heroic, they shape and reshape who counts as a hero.

So it matters that Superman — the hero of truth, justice, and the American way — is an undocumented immigrant. It’s the reason why, when Marvel thought it would be a good idea to make Captain America a Nazi, it backfired spectacularly.

And it matters that Robin has come out as queer. (Here the medium matters greatly: Tim hasn't come out to anyone in his life except for the guy with whom he’s going on a date. He’s only come out to us, the readers.) Tim is not the first queer member of the Bat-family. Batwoman debuted as a lesbian, and several other supporting characters are queer. But Robin is the most well-known and established Bat-person to come out.

The Batman universe includes four ‘official’ Robins. The original was Dick Grayson, who has gone on to become Nightwing. Then there was Jason Todd, who was murdered by the Joker but is back as the Red Hood. The current Robin is Damian Wayne, Batman’s son.

And then there’s Tim Drake: the third Robin, introduced by writers Marv Wolfman and Pat Broderick in 1989. When the current writers came to Tim Drake, they came to a character who never quite fit in with the other Robins. He wasn’t an orphan like many of the other Batman characters, nor is he related to Bruce. No, Tim started off as a detective. After Jason Todd’s death, Batman became dark and angry. Tim believed that Batman needed a Robin. So he broke into the Batcave, and convinced Batman to take him on.

Understandably, Tim has been plagued by a lack of belonging, a question of who he really is. He’s not fully Robin and certainly not Batman — no longer a sidekick, but also no desire to superhero on his own. Every solo adventure brings him back to Gotham. Every team he joins (like the Teen Titans), he eventually leaves. He lives in the in-between, which is something of a rarity in comic lore. After reading through years of storylines featuring Robin #3, Fitzmartin felt that Tim’s sexuality “was a missing piece in the understanding of this character.”

Mythically, Batman and Robin are the father and son, the man and the boy. Batman — as Bruce Wayne — is the virile playboy, while Robin is the innocent, wide-eyed boy. Binaries have a tendency to crop up in mythologies, both ancient and modern. Think of the creation story where God creates night and day, land and sea, male and female.

Queer theology reminds us, however, that these categories are not binaries, but ends of a spectrum. “Queer resists a biological essentialism of sex, the gender binary, and assume or required heterosexuality,” Keegan Osinski writes in Queering Wesley, Queering the Church. “I use ‘queer’ as a verb to mean engaging in the practice of problematizing normative narratives and assumptions,” or disrupting “those givens that perpetuate the power structures that baptize and uphold some norms while damning and marginalizing alternative ways of being.” In other words, God didn't create the world to experience binaries: Creation includes both night and day and all the hours and minutes that fall in between.

Tim’s unfolding storyline also challenges normative narratives and assumed binaries. He is neither Batman nor Robin. For a long time, that murkiness sidelined him in the comics’ mythos, just as queer Christians have felt — or been told — they have no place in the life of faith. By queering Robin, the writers reminded us that the world is much more complicated than Batman or Robin, gay or straight. (It’s worth noting that, while many outlets have reported that Tim is bisexual, the character himself hasn’t labeled anything.) Issue #6 has staked out a space for Tim within the ‘and’ of ‘Batman and Robin.’ By making room for Tim, the writers shift our modern mythologies away from the ‘either/or’ binaries toward the inclusive ‘both/and.’

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!