The assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani put the United States dangerously close to all-out war with Iran. The U.S. and Iran avoided this outcome, for now, due in part to anti-war activism within the United States — like the religious leaders who called on Americans to pray for peace. The week after the action, the House of Representatives approved a resolution restricting actions President Donald Trump could take against Iran.

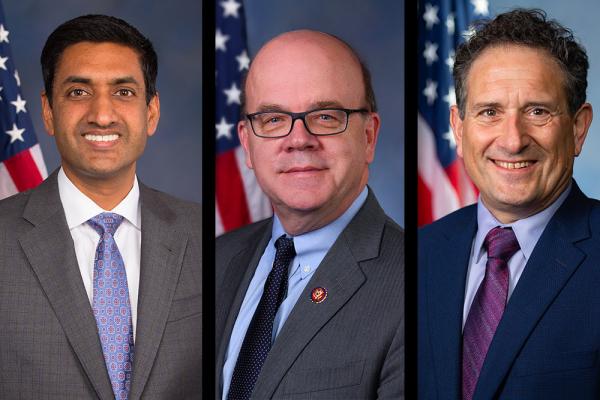

I interviewed Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) by phone on the same day he voted in favor of the resolution. He spoke about how his faith, "Gandhian Hinduism," informed his anti-war views. I was struck during our interview about the diversity of religious views that informed anti-war activism. I asked Khanna's staff to recommend other members of Congress to interview. Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.), who is Catholic, and Rep. Andy Levin (D-Mich.), who is Jewish, both shared their own thoughts in written responses to the same questions.

Some answers have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

How is the activism by faith communities impacting our national debate about war and peace?

Khanna: Faith communities have played a helpful role. Pope Francis has called for dialogue and self-restraint between the United States and Iran. The pope has also played an incredibly thoughtful role in trying to resolve the conflict in Venezuela. So you've had religious leaders influence public opinion to move beyond war as the way to solve problems. And you've had the Dalai Lama in India talking about human rights and dialogue and the need for peace. Many activists in my district appeal to faith. There is a multicultural faith organization with people of the Christian, Hindu, Islamic, and Buddhist faiths. Many peace marches, peace rallies, and advocacy efforts with members of Congress are inspired by this interfaith community. The interfaith community has also spoken out on what's happened at the border, about gun violence, and environmental causes. I've seen faith communities mobilize on issues of social justice.

McGovern: A key component of my faith is the promotion of peace, justice, and human rights. I draw great inspiration from the many faith-based communities that I represent who make the moral argument that we should be dedicated to promoting peace and justice. People always say 'budgets are moral documents' and I couldn’t agree more. Yet the budgets we produce out of Congress are always heavy on weapons of war and all too often negligent when it comes to helping feed to poor or help those in need. One of the reasons I feel so strongly about fighting against war is the teachings of my faith. I think activism by faith communities against war is some of the strongest activism because it reclaims the high ground and forces those who want war to explain why they think violence is morally justified. And often they have no answer because violence is almost never morally justified.

Levin: Of course, there is a long tradition of people of faith and faith leaders opposing war in general and specific wars as a matter of conscience. The current spiraling tensions with Iran represent a call to action for people of faith to put our bodies on the line for peace. As Rev. King said, 'Man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love.'

How do you draw inspiration for your own views on war and peace from your faith?

Khanna: My commitment to human rights and peace comes from my grandfather who spent four years in jail alongside Gandhi during India’s independence movement. I’ve read a lot of Gandhi's’ work because it’s been personal to me because of my grandfather. Gandhi has shaped my thinking and he drew inspiration from the Bhagavad Gita and Hindu philosophy. My own faith is a Gandhian Hinduism and Gandhi also talks about the influence of Jesus Christ, Christ as nonviolence par excellence. Christ’s work and the sermon on the mount as well as the Bhagavad Gita influenced his satyagraha in his resistance to the British. My reading of Gandhi and Gandhi's reading of Hinduism and Christianity have shaped my views on human rights and peace.

McGovern: When I was in college, I started drifting away from the Catholic Church because it just didn’t seem relevant to me. A lot of what I was being exposed to seemed too focused on ritual and not on action and it wasn’t particularly inspirational or exciting. In the 1980s, I was sent to El Salvador by my boss, Congressman Joe Moakley, to monitor the human rights situation there. Later, I was the lead congressional staffer sent to investigate what happened in the brutal killing of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter. I had worked with several of the priests who were killed before, and they were friends of mine. What I discovered shocked me. We uncovered that some of the soldiers that conducted these brutal assassinations had been trained by the United States government, and our findings led to a major change in U.S. policy.

The Jesuits were killed for what they believed. They were killed because they fought for peace. And during my time with them in El Salvador, I was exposed to a more action-oriented type of faith where it wasn’t just about 'let’s tell others to feed the hungry, and help the homeless.' It was 'feed the hungry.' It was 'help the homeless.' It was about directly standing up for the oppressed. And this inspired me and, really, changed my life. This was a vision of the church that was about uplifting the poor and making a tangible difference in the quality of life for everybody and working to make peace instead of just talking about it. This was not just talking about fairness, justice, and peace – this was about living out those values in your day-to-day life.

I found that incredibly exciting. It brought me back into the church because I discovered a part of the church that appealed to me and it made it feel that my religion – my faith – had a purpose. It wasn’t just about rituals, it was about action.

Levin: I have been a peace activist since my college days. I organized against President Carter’s reinstatement of draft registration after the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1980. I was a peacekeeper trainer for demonstrations against nuclear war at the Rocky Flats plant in Colorado around the same time. I helped organize and lead demonstrations to try to prevent the U.S. from invading Iraq, and so forth. What role did my faith play? I am Jewish, but I was studying Buddhist philosophy and practicing Buddhist meditation in the 1980s, and the Buddhist belief in nonviolence (ahimsa) was certainly an influence. Judaism has played an increasingly important role in my life since my mid-thirties, to the point that I have been on the board of both synagogues I belonged to in the last thirty years, I served as president of my current synagogue until I was running for Congress, and I conceived and helped create an organization called Detroit Jews for Justice, which is one of my favorite ongoing projects (although I don’t contribute much to it anymore!). But even as a young man, I took the words of Isaiah to heart — 'They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.' Perhaps my bottom line is the belief that every human is equally precious and sacred and to be respected fully. I expand that out to all animals and our Earth itself, which is why I am so concerned about the horrifying damage war often does to ecosystems and the environment. These beliefs in human rights and the sacredness of our planet are at the core of my spirituality.

In many progressive spaces, it's taboo to discuss religion. Why should progressives highlight religious voices and make faith-based arguments for their policies?

Khanna: The great movements of social justice and racial justice are steeped in religion. Gandhi, King, Rev. Barber with the poor people’s campaign, Abraham Lincoln. When you are looking at a vision of a better world, outside your own family or your own nation, then the appeal to something bigger than oneself, something higher, gives you the proper humility and the proper sense of empathy to make a difference in other peoples’ lives.

McGovern: I think that, sadly, the right-wing has coopted religion for their own political purposes. For some reason, it seems like progressives have always been put on the defensive when it comes to our faith. My faith is not based on exclusion or division. My faith is based on hope and love and action. I think the right has purposely tried to make religion their own, and quite frankly they have no right to do that. I am a Catholic, and there are Catholics that I don’t agree with politically, but this Church is as much my Church as it is their Church. Based on my understandings with the teachings of the Church, I think I’m faithful to my religion.

The God that I believe in says it’s not OK for people to go hungry. It’s not OK for people to be mistreated of for their human rights to be violated. The church I believe in believes that everybody is important, everybody is valuable, and nobody is invisible. I think that things are changing, though, because I have seen the faith community on the left working to really organize and mobilize and fight back against injustice and the apathy that has grown all too common in our society. I think of Nuns on the Bus and Sister Simone Campbell. I think of Jim Wallis at Sojourners, and I think of Pope Francis and his commitment to the poor and to helping refugees, and I see a resurgence of organizing on the left to take back this ground that has been ceded and reclaim religion as an issue for everyone. I don’t think progressives should shy away from faith or from embracing religious voices that are speaking up for the things we believe in.

When you look at some of the great movements in this country – for example the civil rights movement — the people who were in the marches and led the fight for voting rights, many were leaders in various faith-based communities. Many people who have led the cause against the death penalty have been part of the faith-based community. The people who have been so eloquent in advocating for SNAP benefits for poor people have been in the faith-based community. People who advocate for refugees have been in the faith-based community. We shouldn’t shy away from who we are because, for a lot of us, a lot of what we stand for has been informed and guided by our faith.

Levin: I’m a huge believer in people coming to the table as they are, openly expressing their beliefs and the basis of their beliefs. As a religion major, my perspective is that when we call people religious, we are simply putting a label on their world view, on how they draw meaning from the world. But think about it — people who are secular, agnostic, and even atheist have world views just as much as people of faith — and they have their own systems of morality and, to use religion-major words, their own ideas about ontology (what really is) and eschatology (what happens after we die, or in the end). In other words, we all have beliefs akin to what has traditionally been called religion, whether we are religious or not.

What we all share in common are values. Each of us has values that transcend our narrow or selfish interests. It’s so important to make faith-based arguments for policies because they help us speak to the values of people of faith like me, and arguments about values and feelings are more powerful than arguments about facts alone. So I’m a big believer in speaking openly about my faith and in connecting with others about their faith. What is more, since I know humanists and secularists also have deep values, I don’t think speaking in terms of deeper meaning and beliefs necessarily alienates them — it can bring us all closer together in a web of human connection.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!