During some of the most intense periods of fighting in the Syrian civil war, the maternal mortality rate in Washington, D.C., was worse than it was in Syria.

Reading that statistic shook me to my core. The first time I came across it, I was in graduate school studying to become a social worker. A cold feeling pooled in my heart and dropped to my stomach as I absorbed a report that found Syria’s maternal mortality rate rose from 26 to 31 deaths per 100,000 live births from 2007 to 2015 — an increase researchers attributed to the nation’s ongoing civil war and the subsequent deterioration of its health care system. Meanwhile, during the same period, maternal mortality in the U.S. capital reached 33 deaths per 100,000 live births. A recent study found that the 2021 maternal mortality rate in the U.S. was greater than any other high-wealth nation, including France, Germany, the U.K., Canada, and Australia.

For all the power and might the U.S. claims to have, this country chooses not to save the lives of some of our most precious members: mothers and children. I was amazed that lawmakers would sit idly by and allow pregnant people — including their own mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts, wives — to face the risks of childbearing without necessary support. As a person of faith, I thought about scripture’s clear instructions not to “withhold good from those to whom it is due, when it is in your power to act” (Proverbs 3:27).

I eventually did become a social worker, so allow me to get nerdy for a moment: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define maternal mortality as a death that occurs during the nearly two-year period that includes pregnancy, delivery, and the year after. Common causes of death include severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure during pregnancy, or delivery complications. (Maternal mortality is different from maternal morbidity, which refers to “any short- or long-term health problems that result from being pregnant and giving birth.”)

In other words, our country is rolling back reproductive health access in the name of “choosing life” while refusing to support life’s development in utero and post-birth. We also have not ensured that people who give birth or care for children have paid family and medical leave, workplace protections, or even access to health care facilities. In states like Mississippi and Alabama, budget pressures are forcing many rural hospitals to close, cutting off the only point of care before, during, and after labor.

The maternal mortality crisis is even more alarming when you look at the disparities between different racial and ethnic groups. Overall, Black women and American Indian/Alaska Native women are 2 to 3 times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause than white women. And that disparity can’t be blamed on racial disparities related to poverty or family life; a Black mother with a college education is still at 60 percent greater risk for a maternal death than a white or Hispanic woman with less than a high school education.

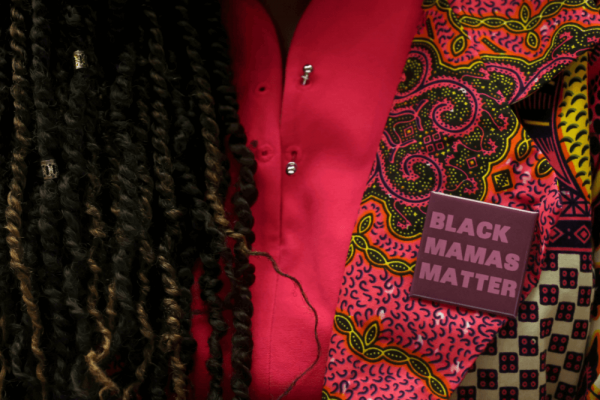

This isn’t an issue of class; it’s about racism, especially the unequal treatment of Black people in the medical system. Of course, the roots of medical racism — including horrific experiments the founder of modern gynecology conducted on enslaved Black women — are centuries old and still evident today: Recent studies have shown that compared to white patients, Black patients are less likely to receive appropriate pain medication or referals to specialty care. Mistreatment during maternity care — including verbal abuse; loss of autonomy; and being ignored, refused, or receiving no response to requests for help — is more common among women of color. Even Serena Williams had to fight against that racism when she gave birth and almost died due to pulmonary embolism.

Racial disparities in maternal mortality are also influenced by the biological consequences of racism. Arline Geronimus, a public health professor at the University of Michigan, coined the phrase “weathering” to describe how the repeated stress of social and economic adversity and political marginalization caused Black people to experience early health deterioration. In other words, the cumulative experience of racism has physical consequences. This problem is so real and pervasive that policymakers from more than 50 American municipalities and three states have formally highlighted racism as a public health crisis since 2019.

Studies have shown that the stress associated with racism isn’t just an issue for the mother — these stresses are intergenerationally passed on in utero and follow children throughout their life cycle. For example, one briefing from the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation found that “even when controlling for certain underlying social and economic factors, such a as education and income,” maternal and infant health disparities, including increased risk for low-birth weight and pre-term births, persist at higher rates among Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native women. A 2020 report from the Center for American Progress put it this way: “The long-term psychological toll of racism puts African American women at higher risk for a range of medical conditions that threaten their lives and their infants’ lives, including preeclampsia (pregnancy-related high blood pressure), eclampsia (a complication of preeclampsia characterized by seizures), embolisms (blood vessel obstructions), and mental health conditions.”

Black women and babies are dying because of historical and systemic racism impacting us on a neurobiological and physiological level; what other reasons do people of faith need to hear before they will name the disparate rates of maternal mortality a sin?

I can’t help thinking of my mom, who had her own life-threatening pregnancy complications after having me. I think of what it would have been like to live without her, to have been raised without her, and it deeply troubles my heart and soul that there are others who have not been so lucky. A large part of my faith hinges on the understanding that God does not want us to suffer, but rather calls us to run toward the suffering of others. Scripture is very clear when it tells us, “If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together” (1 Corinthians 12:26).

While it may be easy to look away from this crisis because the acute burden is being experienced by Black and brown women, I desperately urge you to think again; when one part of the system is suffering, the rest of the system suffers with it. The Black maternal health crisis is exposing cracks in our maternal and newborn care system, but addressing these fundamental issues will create a baseline system of care that benefits all women and children in the U.S. One of the greatest opportunities for change is the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, a must-pass package of bipartisan bills that would course correct the current flaws in our maternal, newborn, and child health care system. The legislation, which would support states and localities in addressing this crisis, would adopt a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to creating maternal equity for Black mothers and their children. This bill would also improve and increase the workforce and address maternal rural health issues, which would better our economy and country as a whole. I urge everyone, especially people of faith, to let your elected representatives know you support this bill and remind them of their sacred duty to protect mothers and children.

There is no reason that Black and brown women should experience such high rates of maternal mortality; the only reason this disparity exists is because of racism. And since racism is social behavior we can change, I believe people of faith have a God-given duty to address how this behavior impacts vulnerable women and children. We must not sit idly by and allow this crisis to continue.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!