America’s religious landscape has changed.

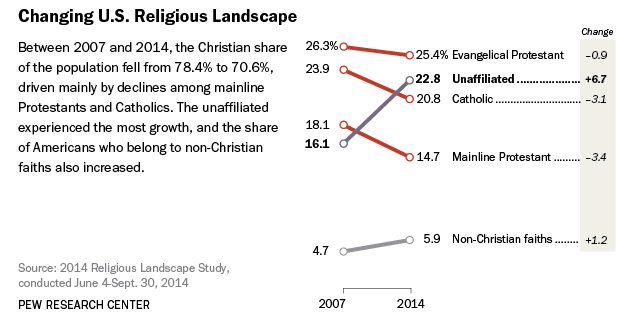

According to a new study from the Pew Research Center, there are markedly fewer Christians and more “nones” — those who identify of no faith at all — in the U.S. than just seven years ago.

In the wake of this news, many critics have lost themselves in the question of who’s winning. Are evangelicals really losing ground? Is secularity finally making progress? Is it just the liberal churches continuing their mainline decline?

But this isn’t a crisis. We don’t need to defend ourselves. We don’t need to obsess over whose team is in the lead. But we also can’t just shrug our shoulders. If we have any faith that Christianity has value in the public sphere, we should be reasonably concerned when people begin to see little importance in Christian identity.

As church attendees and pastors, our energy is best spent asking what we can do and how we should respond — whether this is even a problem.

Interestingly, critics across a broad array of identities — whether liberal or conservative, mainline or evangelical — seem to argue this trend isn’t necessarily bad. But they do so for very different reasons.

Ed Stetzer, statistician and contributing editor for Christianity Today, claims, “Christianity is not dying; nominal Christianity is.”

In his eyes, many who already weren’t very serious about Christian faith are simply giving up the pretense, especially in a culture where it is increasingly costly to identify as Christian. Stetzer calls this shrinking trend “more of a purifying bloodletting than an arrow to the heart of the church.”

Or, as Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, puts it, “Christianity isn’t normal anymore, and that’s good news.”

As a native of Colorado Springs, a bastion of evangelical organizations but mostly pseudo-evangelical religious identity, I can attest — “nominal Christianity” is frustrating. When people who treat Christian faith as a vague “label” feel empowered to be more consistent with their true, secular beliefs by leaving the faith, this is a good thing, both for them and for churches. Churches are freed to become countercultural communities of disciples seriously trying to follow Jesus, rather than social clubs vying for relevancy.

But we should be careful with how we talk about those who leave their Christian identity behind. Some who leave the church do so for painful reasons. The language of a “purifying bloodletting” may be helpful when wealthy young adults searching for romance begin to leave the church, but what about when the marginalized simply can’t bring themselves to identify as “Christian” as they hold back tears of rejection? We need to listen to these cries.

On the other hand, Serene Jones, president of Union Theological Seminary, wonders, “Is it always bad when churches shrink?”

In her view, “in a lot of mainline communities, the line between what it means to be in the church and out of the church is a very fluid line” — especially compared to the line in evangelical churches.

She implies that mainline numbers may seem to lower only because the whole question of Christian identity is less important to attendees of those churches. On the one hand, President Jones’ words should be met with applause. We should certainly be less concerned with who’s in and who’s out.

But it’s also a problem if people are leaving churches because churches offer nothing distinctive or particular. If the communal, justice-minded values of the church can be found elsewhere, if they look just like a progressive meeting of secular millennials, what’s the point of Christian identity?

If church is simply “the dull exponent of conventional secular political ideas with a vaguely religious tint,” as Stanley Hauerwas said all the way back in 1985, why go at all?

Serene Jones is also asking this question herself. As she put it, “What are the incentives to stay?”

The answer, I think, is in a humble confidence in the value of Christian identity: in our scriptures, in our tradition, in our communities, and in our God. We confess that Jesus is Lord, and despite all its baggage and all its misuses, this continues to be a profound claim. Our scriptures tell the story of the people of God participating in God’s redemption of creation, a process inaugurated by the resurrection of a Jewish criminal.

For all our efforts at loving individuals, this is not a story we can live as individuals, by ourselves, on our own. We need community. And we need historic community — one that spans space and time. We need a story that grounds us, and elders to guide us. We need the church.

Of course, the church has been far from a perfect community. Sometimes it has done great, great harm. Justice must roll down like a river. But if we strip away all the church's particularities in an effort to attract and accommodate modern believers, Christian identity will inevitably lose any real value.

As Rachel Held Evans, an evangelical-turned-Episcopal Christian, recently urged mainline churches, “Please, please don’t be afraid of being distinctly and unapologetically Christian! Don’t be afraid of pushing and challenging us!”

In the end, the question, “Is it good or bad when churches shrink?” depends on why people are leaving the church. It’s not always bad. It can actually be very good. But when the marginalized are forsaking their Christian identity because they see no place for themselves and when young adults see nothing in progressive Christian faith that they can’t find at a public library or local union hall, we have a problem on our hands.

Christendom has long been over. The real question is: Now what?

Ryan Stewart is Online Assistant for Sojourners.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!