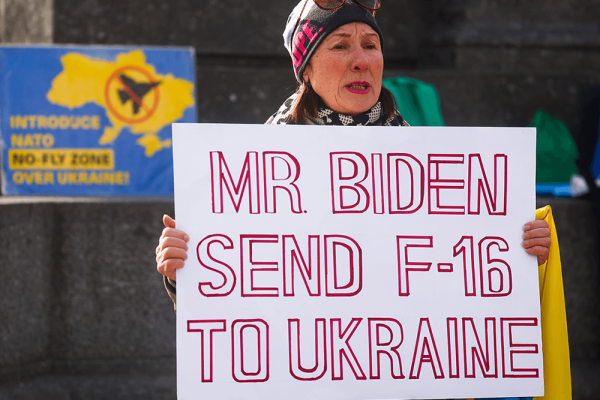

In his recent opinion essay, “Negotiating Peace in Ukraine Isn’t Surrender. It’s Christian,” Adam Russell Taylor argued that “the ability to imagine and advocate for alternatives to war” — including the war in Ukraine — “is a core Christian responsibility.” While noting Ukrainian people have the right “to defend their sovereignty from Russian President Vladmir Putin’s imperialistic aggression,” he argued that “it’s become increasingly clear that the ongoing massive weapons dump by the U.S. and NATO into Ukraine is not leading to the end of war but may instead be prolonging it.”

Sojourners received lots of responses from readers who both agreed and disagreed. We are sharing some of those responses — along with a note from the author — in order to spark more conversation and thought about the role of Christians in peacemaking.

All responses are shared with permission, and lightly edited for length and clarity.

A moral failure

“War is always a moral failure. War is always an unjust tragedy brought down on those most vulnerable.” Is it a moral failure to defend your country against conquest by a ruthless tyranny? Is Ukraine another “small country far away about which we know little”? If this country, and its people and their leaders, wish to retain their land intact and whole again, how is that a moral failure on their part? Would it not be a failure on our part if we lectured them on their rights and aims and on their own willingness to sacrifice in pursuit of those aims? —Ron Partridge; Kent, United Kingdom

“Wise as serpents and innocent as doves”

If we as Christians are to be both "wise as serpents and innocent as doves" in our peacemaking, we need to not only work with those creating the conditions for peace but also confront those fanning the flames of war. Both at home and abroad various forms of Christian nationalism have promoted violence for generations, and we see this yet again playing out in Russian Orthodox support for violence in this conflict. … Until Christians find the courage to call out the support of violence within its own ranks, its witness to peace will always be compromised. —Mark Douglass; Portland, Ore.

Responding to unjust aggression

Ordinarily I'm VERY sympathetic to this line of reasoning, especially since I'm a Catholic seminary graduate (M.Div.). At the same time, I'm concerned that we run the risk of resurrecting Neville Chamberlain if this is the course we plan on following in the face of the crime of unjust and destructive aggression against Ukraine and its people perpetrated by the Russian criminals. —John Ghormley

Peace or pause?

Your article is compelling. My problem is that if Putin gains anything from these attacks, he may stop now but is also very likely to start again. I don't see peace as peace but pause until he feels he can try again. —Penny Burgett; Radford, Va.

Diagnosing the barriers to peace

I partially disagree with Rev. Taylor’s recommended way forward in Ukraine. While peace is certainly the end we should seek as Christians, we must begin with a clear diagnosis of the barriers to peace. In Ukraine, the barrier to peace is Russian occupation and atrocities against Ukrainian civilians on Ukrainian soil every day. … Rev. Taylor is correct that war is a moral failing. But it does not follow that people who are being slaughtered have a clear moral obligation to lay down their arms while the oppressor remains. —Dan Nejfelt; St. Paul, Minn.

A response from the author, Adam Russell Taylor

I deeply appreciate the thoughtful responses we received in reaction to my article. The war in Ukraine continues to dominate the news this week, with both President Joe Biden declaring America’s unwavering support to Ukraine during his visit to Kyiv and Russian President Vladmir Putin doubling down on his propaganda that the West began the war and announcing plans to suspend Russia’s participation in the New START nuclear arms treaty.

I knew my call for peace talks would be a provocative one, particularly in light of the current realities on the ground. Like the other beatitudes, peacemaking is often a countercultural commitment. I hoped my article would spark a more vigorous dialogue within the church about what peacemaking means and requires. However, I don’t want my presumption toward waging peace in this moment to be misunderstood. Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine is both a blatant violation of international law and a form of tyranny. According to just war theory, Ukraine is fighting a just war. As I wrote last week, Ukraine has every right to defend itself from this imperialistic aggression.

The main purpose of my article was to shine a spotlight on how the fixation on escalating the war can foreclose the prospects for peace. I recognize that a mediated peace will be extremely challenging and will likely take tireless effort and significant time. Yet the current political discourse around the war in Ukraine presumes that the only path to reach peace is through an escalation of the current conflict. According to this calculation, peace is only possible if Ukraine — with substantially more Western military aid — defeats Russian forces and can deter future Russian aggression. This mindset essentially precludes any possibility of a mediated or negotiated peace and forces us to accept the inevitability of prolonged death and destruction. The painful fact that this war is being fought largely between Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox Christians only reinforces that a prolonged war constitutes a failure of the Christian witness.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!