The amber appears to ooze across the floor like slow-flowing lava. Containing found objects and materials sourced from Salvadoran communities around Los Angeles, Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s artwork is expansive and expressive of the materiality of often-marginalized Central American migrants in Southern California.

His artistic craft, Aparicio said, speaks to the innovative, resourceful, and resilient voices of migrants throughout the city and beyond. Artists of many kinds hope works like Aparicio’s can tell new kinds of immigrant stories — ones often full of faith and spirituality, migration and baptism, encounters with Jesus and varying experiences with church life.

Amid the leaves, bones, broken dishware, condom wrappers, beer holders, and archival papers in Aparicio’s work is a single flier for a church — a “Casa del Dios” advertising their services with Jesus’ words in bold red across the top: “I am the way, the truth, and the life.”

The installation, on display at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, hints at how immigration and faith are represented in various artistic mediums.

While political conversations about immigrants and immigration policy tend toward broad, often dehumanizing stereotypes, artists such as Aparicio are using their art to help viewers reflect on the deep, and expansive, experience of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in the U.S.

Giselle Elgarresta Rios, the first Cuban-American woman to conduct at Carnegie Hall in New York, wrote that art — perhaps more than other media — can help us better “see the souls of immigrants.”

Painting the pain and suffering

Sister Norma Pimentel, executive director of Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley in the Archdiocese of Brownsville, Texas, is one of the nation’s leading voices calling for more just immigration policies. But along with overseeing several programs to help suffering families in her community, Pimentel has also taken up painting.

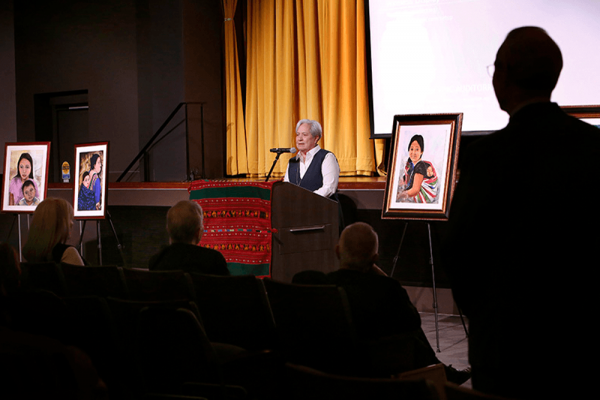

During an April talk at Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago, Pimentel unveiled copies of five oil and pastel paintings of women and children who sought shelter after being released from detention centers at the border.

With the immigrants’ permission, Pimentel takes photos before painting their portraits over the course of three days. “I start one day, and the only thing I do is the eyes and the expression, because that’s the most important part,” Pimentel said, “and then once I do that, the next day I finish the rest, and the third day I just touch up whatever I need to touch up, and that’s it. It’s done.”

The portraits frequently feature migrant mothers with their infant children, sitting on the lap or slung on their backs and wrapped in rebozos, or large, woven shawls. One of her paintings, of a young boy Pimentel met in 2014, was presented to Pope Francis.

It is the often-grim depth of migrant experiences, Pimentel said, that inspires her art: “We see the pain and the suffering that they’ve been carrying for all their journeys.”

Pimentel was a fine arts student before going on to study theology and psychology and, eventually, taking her vows with the Missionaries of Jesus. She said she sees, and senses, God’s presence and love in the faces of the migrants she photographs and paints.

“They’ve gone through so much,” she said, before commenting that she encounters Jesus in the migrants she paints and meets along the way. “He very clearly told us that we will find him in them: those innocent, fragile people that come to the border in the United States and are simply asking for an opportunity for life,” Pimentel said. “That’s all.”

Entre Tu y Yo/Between You and Me

“The border,” said New York-based artist Francisco Donoso, “is not just defined by the U.S./Mexico border. It is with the individual.”

The border, in other words, is found at the parking lot of a Home Depot in Chicago, the school where people are teaching migrant children in New York, and the farms in Florida where people who are undocumented harvest blueberries, mushrooms, and tomatoes.

Donoso’s earliest memories are of drawing pictures as a young child in Ecuador. “From a very young age,” he said, “people could see I was inclined toward art.” When his family migrated to Miami, Donoso was enrolled in a magnet arts school and continued his art education through college, where he graduated from the State University of New York at Purchase’s renowned arts school.

“After that, it was New York City,” Donoso said, where he has become regarded as a pioneering, transnational artist using mixed media to create works that explore what he calls “the psychic spaces of migration” — its psychological, emotional, spiritual, and unseen terrains of mind, body, and soul.

A career in the arts was not always in the cards for Donoso. Growing up in evangelical and Pentecostal churches in Miami, Donoso’s first inclination was a calling as an urban missionary. Even after finishing his bachelor’s degree in fine arts, Donoso still thought he might return to Miami to work with its poor and marginalized communities. “I always had a big heart for helping and service,” he said. “I always saw myself working in that space.”

But in the last two months of college, Donoso had a bit of an awakening. Growing up as an undocumented, gay migrant with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status, he felt church spaces did not leave room for him to be fully himself. And so, he made the decision to move to New York and become a full-time artist.

Donoso got his first big break as a fellow with Bethel University’s since-closed New York Center for Art and Media Studies. For nine months in 2011 and 2012, in a studio on 28th Street, Donoso began to explore themes such as light and memory through abstract art.

Mixing and remixing color, photography, poems, and material motifs such as a chain-link fence, Donoso’s work is highly personal. With names such as “Entre Tu y Yo/Between You and Me,” “Celestial Hood,” and “Origins,” his pieces explore “the immigrant experience through patterns and forms that evoke networks of movement” across, through, and in various landscapes, both urban and rural.

Donoso’s images confront the viewer with tangled webs of interconnecting lines, splotches of mixed pigment, and overlapping smears, interposed with gaps and shadows. This complex visual representation is meant to reflect his experience as an immigrant from Ecuador, wherein Donoso found it “impossible to stabilize myself within one cultural identity.”

In many ways, Donoso’s journey through the world as an undocumented person – and also as someone who grew up in the Christian church and later came out as a queer artist – has been a series of crossing thresholds. All of these, Donoso said, were spiritual journeys. “I think about migration as a process of transformation,” he said. “As you move through space and time, you become something else within the stories you live.”

As people spend time with his images and the ideas they inspire, Donoso hopes they might be drawn inward to discover divine spaces within themselves and their own stories. Whether via the bold, abstract splotches of acrylic color and pastel light or the quieter crisscrossing motif of chain-link fences, Donoso wants viewers to zoom out from the geopolitical struggles of immigration in the U.S. to think about borders as thresholds for possible connection.

“The fence, as much as it divides, can also be seen as a network of connections,” he said, “as a network of solidarity.

“There are so many kinds of migrant experiences in the world, so many different ways to experience the tragedy and laws of immigration,” Donoso continued. “So, solidarity across borders is extremely important as a way to bring us all into the same awareness — that we are all under the same sky and, in the end, we are extremely connected.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!