“Love casts out fear, but we have to get over the fear in order to get close enough to love them.”

- Dorothy Day

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Catholic Worker Movement — best known for its hospitality houses that dot the nation, bringing together communities of individuals in need and offering them housing and love.

It was in that vein that Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove and his wife, Leah, began Rutba House in Durham, N.C., after experiencing what he calls the “Good Samaritan story:” While the couple were on a peacemaking trip in Rutba, Iraq in 2003, friends were injured in a car accident, and local physicians gracefully cared for them.

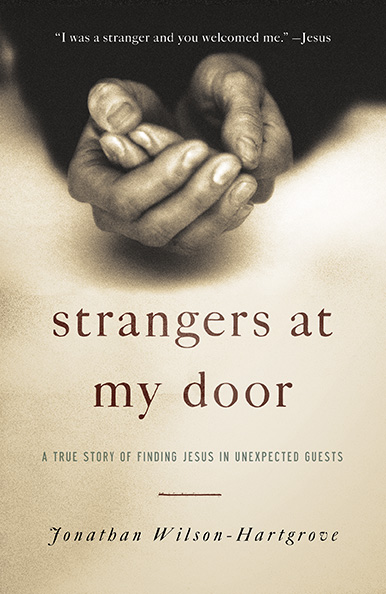

Jonathan and Leah returned to the states looking for a way to extend the same type of love and welcome they received in Iraq. Ten years later, Rutba House holds countless stories of transformation through community, which Jonathan recounts in his book Strangers at My Door: An Experiment in Radical Hospitality, out Nov. 5.

Upon first glance, the arc of the narrative does seem radical. The hospitality house welcomes strangers in to live as part of the community — even at midnight, even when they might not pass society’s presentability test, even when the host is tired, even when they come straight from prison.

“I think part of what I’ve learned over the past 10 years — what Jesus is revealing to us through this call to greet him in the stranger — is something basic about who we are and who we’re made to be,” Wilson-Hartgrove told Sojourners. “All of us are called to hospitality — not just as Christians, as human beings. Because humans can’t live alone.”

He says seeking out Jesus’ command to offer hospitality and to be a neighbor to others doesn’t have to look exactly like Rutba House. It can be as simple as sharing lunch with someone asking for change and sitting down to learn her story. It can look like a lawyer offering help to an undocumented immigrant when they can’t pay. It can look like thousands of other small but inviting “interruptions,” as he calls them.

“We can either open ourselves to that [connection] or we run from it, we hide from it, we build walls around ourselves and close ourselves off. But when we do that, I think a little of us dies,” Wilson-Hargtrove said.

Some see this type of “radical hospitality” as dangerous. Surely, the assumption goes, when you welcome in anyone and everyone, there are bound to be some negative consequences. Jonathan admits that they’ve been stolen from over the years, but, “we’ve never had a break-in — because our doors are always open,” he adds with a laugh.

Society bars itself from the outside with gated communities, security systems, and deadbolts. The Wilson-Hartgroves invite the outside in with open doors. Jonathan said he gets the questions occasionally — the “don’t you worry about your kids” questions.

“I think there’s something to be gained from the security of community and from friendship and from letting people know that you care about them, and so they will care about you too,” he answered. “Of course, we’re never safe. I’m not saying that makes us safe, but I don’t think that our hyperactive attempts to secure ourselves make us safe either.”

“I think there’s something to be gained from the security of community and from friendship and from letting people know that you care about them, and so they will care about you too,” he answered. “Of course, we’re never safe. I’m not saying that makes us safe, but I don’t think that our hyperactive attempts to secure ourselves make us safe either.”

And, as Jonathan says, removing the façade of safety allows for real relationships — and those relationships allow you to see the realities of life for people we are called to be neighbors to. They are people who are undocumented, homeless, have suffered addiction, have been swept up in an unjust mass incarceration system, or were simply never given the same advantages as others. These are our neighbors. And knowing them, living with them, loving them, allows for transformation not only of an individual, but a community — ultimately, perhaps, a society.

In fact, Jonathan’s experiences with ‘the other’ — in this case, the homeless —inspired the community to fight a Durham city ordinance that makes certain types of begging illegal. A judge recently softened tone by offering social services in lieu of jail to 13 defendants charged under the year-old ordinance, and the city council is set to consider revisions to the rules next week.

In his book, the stories Jonathan tells about what happens when you open your heart and your life to others is encouraging and inspiring. It all comes down to relationships — and the God who calls us to enter into those relationships.

“Something deep in each of us cries out against the injustice of poverty and homelessness, prison and addiction. … But numbers can also depersonalize the suffering of people we don’t know but still care about. The hard facts somehow distance us from the emotion of human life. But one person unveils the fullness of our pain and our hope. One relationship can help us see the light that can shine out of a life — the very thing that, though it isn’t a miracle, really, illuminates the way home for each of us.”

- from Strangers at My Door, p. 172 (emphasis mine)

Sandi Villarreal is Web Editor and Director of Online Media for Sojourners.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!