What does it mean to celebrate Passover during a time of rising authoritarianism, climate crisis, and genocide? Every year, Jews mark Passover by reading the Haggadah and by refraining from eating leavened bread for eight days in commemoration of the ancient Israelites’ hurried trip out of Egypt. The Exodus story tells of their journey from slavery to freedom, and each year Jews are commanded to experience this ritual anew, imagining that God is setting them free as if in the days of old.

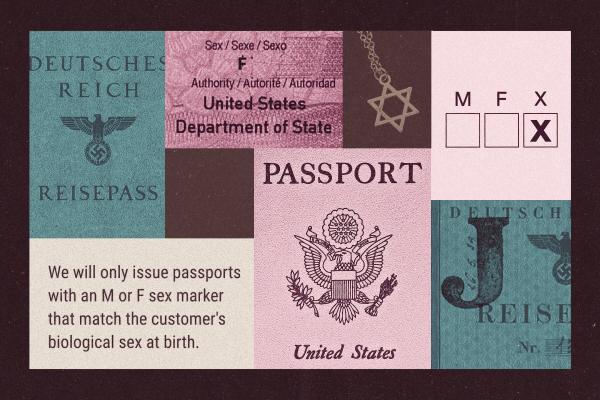

But as the yearly calendar brings us to a holiday celebrating divine redemption and freedom, it’s hard to avoid the despair of this historical moment. There are efforts to dismantle the federal government, expel undocumented immigrants, and advance theocratic ideas to further erode the separation of church and state, all alongside the collapse of the ceasefire in Gaza and violent Israeli military incursions in the West Bank. Meanwhile, the Trump administration appears to be implementing Project Esther. The administration is shutting down pro-Palestine organizing by weaponizing antisemitism rather than actually fighting it, and every day more students and faculty are being targeted for harassment, including having their visas revoked and facing deportation.

While searching the past for examples of how Jewish thinkers grappled with historical injustice amidst the uncertainty of the present moment, I discovered the writings of Marc H. Ellis, a Jewish thinker who died last June and presented a powerful vision that grappled with questions of power, dissent, and universal justice.

In 1987, Ellis published the first edition of his magnum opus, Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation. At the time, he did what almost no other modern Jewish theologian was engaged in doing: He looked honestly at how Palestinian perspectives affected our interpretation of Jewish history and demanded a response from modern Jewish thought.

Just as the symbol of Auschwitz thoroughly challenged European Christian complicity in the Shoah, Ellis argued that Jewish thought must grapple with the weaponization of Judaism’s central ideas to support ethnic nationalism in the Middle East. While most of the other post-Holocaust theologians argued that Jews should embrace political empowerment through the nation state, Ellis envisioned things differently: He insisted that while Jews needed political empowerment, they should reject it if it came at the expense of another people.

Like all great thinkers, Ellis created new language, inventing the powerful expression “Constantinian Judaism” to describe how Jewish institutions embraced certain kinds of political power, much like what Constantine did to Christianity when he made it the official religion of the Roman Empire.

But what animates Ellis’ work is its focus on the central tragedy of 20th century Jewish history: the Shoah. He argues that one cannot understand the Jewish community without recognizing its history of struggle and trauma, represented most horrifically in the Nazi Holocaust that destroyed much of European Jewry. Jewish survivors felt failed by the world, and Ellis points out how many Jewish leaders translated this feeling into a nationalist ethos of self-reliance and insularity.

At the heart of Ellis’ approach was an attempt to grapple with these two seemingly competing histories. While for thousands of years Jews suffered marginalization and offered a witness and critique of injustice, the modern world has seen the state of Israel redefine that paradigm and assert a new vision of Jewish power.

Ellis argued that Jews must resolve this contradiction by returning to the Exodus story and embracing a more complex narrative — one committed to Jewish prophetic dissent, Jewish safety and survival, and Jewish solidarity in a shared struggle for Palestinian freedom. Echoing perspectives more commonly heard today, he argued that the only way for Jews to be truly free is if Palestinians are free, and he insisted on exploring liberation theologies from around the world to offer new material for conversation.

But Ellis’ attempt at creating a dialogue between liberation theology and Jewish thought came with its own set of challenges, especially as it relates to the Exodus. For one thing, Christians and Jews have spent thousands of years in tense conversation, mostly in worlds where Christians vastly outnumbered Jews and sometimes targeted them with anti-Jewish violence. While recognizing these challenges, Ellis hoped that a sympathetic dialogue could open up ideas for Jewish thought and community, offering a new way to grapple with the dangers of political empowerment.

But there’s actually an even deeper problem with using the Exodus story as a template for liberation theology. Robert Allen Warrior, who is an Indigenous scholar and the Hall distinguished professor of American literature and culture at the University of Kansas, argues in “Canaanites, Cowboys, and Indians” that while the Exodus provides Christians and Jews a foundational story of slavery and freedom, it overlooks one key aspect: The God that redeemed the Israelites from slavery is the same God who commanded them to annihilate and drive out the Holy Land’s original inhabitants. Warrior reads the Exodus through “Canaanite eyes,” calling into question the possibility of ever universally applying this story, and notes that the God of the narrative is both a deliverer and a conqueror, a liberating God for some and a terrifying figure to others.

Warrior asks Christians and Jews to center the Canaanites, the last ignored human voice in the Bible, and to acknowledge the dual character of the story while respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples to maintain their own liberation stories outside of the biblical paradigm.

In keeping with Warrior’s challenge, Ellis contended that we must take responsibility for the fullness of these traditions and their material impact. We must acknowledge histories of violence if we ever want these texts to serve as a beacon of hope in the future.

When I reflect on this vision of Jewish liberation theology, I think about the Yovel, the Jubilee year. After God redeems the Israelites from slavery, God provides the law to Moses as a moral and legal guardrail to build a just society. In Leviticus 25, the Torah describes how in every 50th year, the Israelites were obligated to restore the land to its original tribal inhabitants. Debts must be forgiven — and slaves, even those who chose to remain with their masters — must be freed. Yovel marked a time of liberation, a restarting of the world to ensure its alignment with the Torah’s aspirational ethical vision.

But it also forced the Israelites to acknowledge something deeper: Life is fragile. By restoring the structure of society to its original form, the Jubilee reminds us that what we take for granted is far more delicate than we think. We come to this world as guests with unique ethical responsibilities to be of service to one another. In this current moment, maybe there’s an even more essential Jubilee, one that invites us to acknowledge our shared fragility, and brings forth a spiritual reframing to create new ways of embracing and caring for one another that don’t come at the expense of more vulnerable people.

So, how am I entering Passover this year? More so than other years, I’m feeling the need to acknowledge the harm these texts have caused before moving to how they can inspire new futures. By way of that grappling, especially through engagement with contemporary Palestinian theologians, I hope to learn new insights that offer ways to put our ideals into practice and to unlock new meanings in this complicated story of slavery, hope, and liberation.

As we take on the challenges of the current moment, there are traditions of justice that can inspire us to rally across faiths and traditions, giving us the courage to push back on authoritarian politics. As Ellis wrote in Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation, “Faith tells us that history is open; that empire does not have the final word; that community is possible. In the times when this hope seems impossible, the unexpected happens, and what previously was impossible becomes a possibility.” Perhaps revisiting and reviving Jewish liberation theology is one such tradition. Perhaps one day it could even help bring about a new Jubilee.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!