Opinion

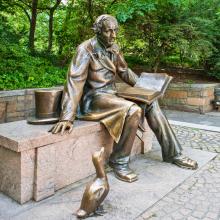

Image via Gimas / Shutterstock.com

A starting point is recognizing the truth that war is never noble or courageous. Noble and courageous acts occur during war, but war itself is always the ultimate human failure and must never be portrayed as anything else. War is the expression of our worst impulses — killing and maiming one another while destroying the many good things we've built together.

Our toxic apathy is rooted in a lot of places, but sadly we don’t have to look any further than the church itself to find several excuses to not care for the poor, vulnerable, marginalized, and downtrodden in our community and in our world.

Fifty-four years ago today (Aug. 28), the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. declared in his baritone voice, which still hangs in the air all these years later, “I have a dream.” A forgotten aspect of King’s witness was his ability to move and bring about change from the “prophetic middle.” The prophetic middle is not about being politically indecisive, indifferent, or even about being a political moderate, as King was none of those. In fact he was far more radical than the domesticated version of his life that is paraded about each January.

Take off your shoes.

No, I really mean it. Right now. Stop what you’re doing. Put down your phone, turn away from your computer screen. Loosen your laces, step out of your sandals, and free your feet from wherever they are currently confined.

Shoes off? Ok, now keep reading.

Take off your shoes, for you are standing on holy ground.

White supremacy has been a staple in much of the American and European Church. This marriage of racism to the gospel is proudly displayed on a mantle when people say America was founded on Christian principles. The so-called return to Christian values means a return to a time when white supremacy was uncontested philosophy and policy.

What now? Where do churches go from here? Here are five initial thoughts I would like to share, knowing the answer isn’t simple — it will take our collective discernment from the whole diversity of our churches to continue addressing our post-Charlottesville way forward.

Many people who don’t study this sort of thing for a living may feel things are moving too quickly, and as such we can fall prey to common "straw man" arguments: “First Confederate statues, then what?” and “We shouldn’t erase history.”

In the wake of the Charlottesville, Va., white nationalist race riot, several writers have reached for the metaphor of addiction to help characterize the gravity of what America is facing and the grip it has on us. It's easy enough to understand why one would choose this particular comparison, especially when you take time to explore how compulsive behaviors affect the individuals engaged in them, their families and friends, and even their brains. The outcomes over time are devastating.

Has your pastor addressed the events of Charlottesville directly? Did they say that the racism and white supremacy are evil and contrary to everything that Jesus taught and lived?

I believe we’re called to be Peters in the world: Proclaiming our belief in God, and calling each other to faithful discipleship. Being supportive and loving is what we are called to do. Holding each other up and encouraging one another is part of our job as Jesus followers. Supporting the last, the least, the lost, and the left behind is our mission.

In their greed these teachers will exploit you with fake news. Their condemnation has long been hanging over them, and their destruction has long been sleeping. — 2 Peter 2:3

On Wednesday, when President Trump shut down his business advisory committees just ahead of his business advisers’ resigning en masse in the wake of Charlottesville, one of his evangelical advisers, Johnnie Moore, delivered a statement on ABC News that concluded the following.

Thousands gathered in front of the White House on Tuesday calling on the administration to protect the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the executive action signed by President Barack Obama that protected 800,000 young people from deportation. They were able to receive work permits and stay in the U.S. in exchange for providing their information and going through background checks. Now, DACA is in the hands of the Trump administration — and the program is under threat by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and nine other state-level officials who plan to sue if the Trump administration does not cancel DACA by Sept. 5.

Last week’s event in Charlottesville that resulted in the death of Heather Heyer is a clear reminder of the unresolved and persistent struggle of our nation with the sin of racism. For more than five years (not referring to the historical struggles) the African-American community has been raising its collective voice, calling out our nation to the pervasive, often deadly, effects of racism. These “deadly effects” are experienced not only in the actual killing of African Americans in the streets of our cities, but also in the denial of full access to the benefits and privileges of our socio-economic systems.

It’s a powerful setup, and the girls’ (and their team’s) journeys are inspiring. But it’s hard to shake the feeling that Lipitz is more concerned with crafting a tidy, three-act narrative than with taking an honest look at who these girls are, and the issues they face.

Of the many shocking images from Charlottesville, one continues to haunt me. White men, mostly younger, are marching and carrying torches in the night with faces full of grim hate and determined anger. It was malevolently reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan’s torch-lit night rallies, with cross burnings and the evil actions and killings that often followed. Even more, it brought memories of the Nazis marching with their torches, slogans, and violence in the 1930s. The neo-Nazis in Charlottesville chanted some of those same slogans.

Somewhere completely outside of all of this,

you are ushering in a kingdom not of this world,

one that rights all wrongs and rules in love.

But for now, here we are.

I have been asked by two dear friends, “how can I be a stronger ally?” Being the slow emotional processor that I am, I wanted to spend some time with this before I answered them. I surely appreciate and love these two individuals, and I appreciate their vulnerability in asking me this question. I am not going to do much coddling here; I don’t know that I believe that love requires coddling. Here are six things you can do to be stronger allies.

Clergy protest the white supremacist rally Aug. 12. in Charlottesville, Va.. Photo by Heather Wilson (@aNomadPhotog) / Dust & Light Photo.

On Friday, I traveled to Charlottesville, Va., to bear witness. What I saw there deeply unsettled me. White supremacists, gathered for a rally at a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, boldly manifested the evil legacy of America’s original sin. Unfolding in streets throughout the city the heritage of whiteness was revealed in full display. Perhaps most disturbing was the unashamed nature of this hate-filled display: In 2017, white supremacists wear no hoods.

And our best chance at fighting supremacy on a daily basis is to know who we are, to know the truth of what we are called to be in the name of Jesus — based on his peace, his shalom, his justice, and based on the fact that all people are equally valuable in their own skin and own cultures. This forces us to take a look at our missionary ideologies, at the way we view light and darkness and what we teach from our pulpits and in our bible studies. It forces us to recognize that people who are outside the institutional church are doing the good work of Jesus, too, and we learn from them.

The crowd that night believed something precious had been “stolen” from them as Christians. And it had to be “reclaimed.”

That long ago bitter sermon provides a warning as Americans ponder this question: Was the lethal violence in Charlottesville a one-time event, or does it represent the future of an America religiously and politically at war with itself?