What do we lose when we trade our humanity for social stereotypes rationalized by religious dogma?

That question is at the heart of an ongoing discussion my son, a junior at Kenyon College, and I are having around the recent suspension of a tenured Wheaton College professor, Larycia Hawkins, for wearing a hijab during Advent and stating publicly (via her personal Facebook page) that Muslims and Christians worship the same god.

In subsequent interviews, Hawkins has revealed that Wheaton's administration repeatedly has required her to reaffirm her commitment to the school's statement of faith after what it deemed possible infractions including: for teaching liberation theology and taking it seriously; for attending a party near a gay pride parade in Chicago; for suggesting more diverse language around sexuality be used in school curriculum; and, most recently, for making statements in solidarity with Muslims.

"I stand in religious solidarity with Muslims because they, like me, a Christian, are people of the book," she wrote in a Dec. 10 post on Facebook. "And as Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God."

Wheaton's orthodoxy police have been after Hawkins for some time, and their gestapoesque tactics are hardly new. In the 25 years since I was a student at Wheaton, professors routinely have been forced out for trespasses such as refusing to discuss the details of their divorces, concerns about sexual orientation, conversion to Roman Catholicism, and "incorrect" ideology.

It's not surprising to many of my fellow Wheaton alumni that the school has deviated so far from the intent of its founders to extend grace and liberty to all humankind — slave and free — in spite of and with flagrant disregard for the civil law at the time.

Larycia2.jpg

Wheaton's trustees and administrators today ought to worry about where this new trajectory is leading them.

In the words of Jesus from the Gospel of Mark 8:36-37, "What good would it do to get everything want and lose you, the real you? What could you ever trade your soul for?" (MSG)

Throughout the last few decades, in its pursuit of a narrow orthodoxy Wheaton has lost its cultural moral compass. The school's administrators have forsaken historic Christian grace for a new kind of fundamentalism, one that blithely would condemn the mass of humanity that falls outside its exiguous dogmatic beliefs to eternal, conscious torment, just as swiftly as it would cut down one of its own for daring to humanize and empathize with those the college administrators clearly deem to be the "enemy" of Christendom, in deeds if not in (public) words.

The problem with such intolerance for different points of view (and the people that hold them), is that it hurts the person who practices it as much as those it intends to dismiss in the abstract.

Bigotry damages your soul.

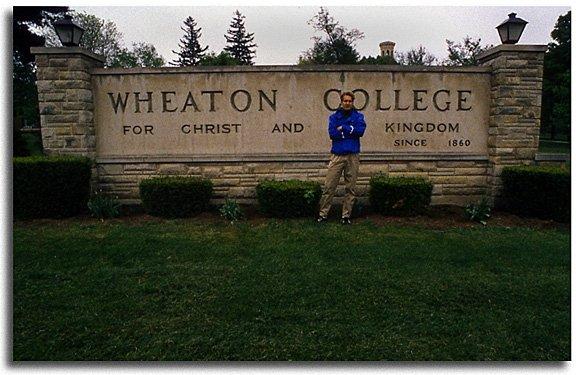

'For Christ and His Kingdom'

Founded by Christian abolitionists in 1860, Wheaton's cornerstones historically were evangelism and social justice. Under the leadership of its first president, Jonathan Blanchard, the college became a stop on the Underground Railroad. At the time, Wheaton was the only institute of higher education in Illinois that admitted women, and in 1866 graduated the first African-American student in the state, Edward Breathitte Sellers.

Carved in stone on the front campus is a large sign that says, "For Christ and His Kingdom." The school's Billy Graham Center is named after its most prized alumnus, a man known as "America's Pastor" who took evangelism into the world and was as changed by those experiences as the people he attempted to reach. Wheaton was about building bridges of liberation with people who weren't white Protestant Christians and helping them fully realize their own potential and humanity.

A key component of grace, an idea that is tossed around Wheaton's campus like a Frisbee, is free choice. And a key component of free choice is having the freedom to think differently.

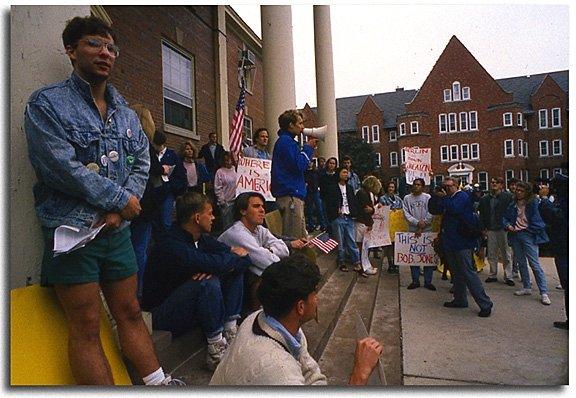

When I was a junior at Wheaton in the spring of 1990, the school's administration offered me choices similar to those they've presented to Hawkins: expulsion or withdrawal. My alleged transgression was a poem I'd penned for an unsanctioned student newspaper. The administration and board of trustees judged the content of my poem, with some implicit sexual imagery, to be unbecoming of a Wheaton College student.

1930059_17713543111_1390_n.jpg

There was no discussion or debating with the college administrators. I was wrong and they were right. End of conversation. Just as it has with many other students and professors who have run afoul of the college's powers that be, administrators invoked Wheaton's almighty Statement of Faith to clean up a disagreement over an idea, and I opted to withdraw and finish my undergraduate degree elsewhere.

See an archival copy of The Ice Cream Socialist with Vanderveen's poem.

The only way that I had to fight back against a ridiculous decision by an activist board of trustees was to stage a public protest of my own with fellow students and professors. We gained national media attention and the liberal arts college was heavily criticized by alumni, the public, and the mainstream media for behavior so obviously at odds with its academic purpose, history, and basic American principals of freedom about speech, religion, and conscience.

Wheaton College is a private institution and appears to have the right to admit and remove students, faculty, and administrators based on disagreements over ideas. The real question for a place like Wheaton that attempts to hold itself to the highest moral standard — For Christ and His Kingdom — is, "Should it behave this way?"

It's a question Edward Sellers and his cohort in Wheaton's Beltionian literary association very well might have debated. In the 1860s, the Belts, as they were known, were dedicated to the ideal of "striving for the greater and better," and held great debates amongst students on topics from economics to ethics, including the lawfulness of slavery.

My son, Schuyler, attends Kenyon College in Ohio, one of our nation's the better liberal arts schools, one founded a few years before Wheaton and affiliated with the Episcopal Church in America. He recently read Ralph Ellison's essay "Twentieth-Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity" in his 19th-century U.S. fiction class, which explores issues of race, bigotry, stereotypes, and humanity.

In his essay, Ellison examines how Mark Twain handles the change in American culture around African-American identity in his book Huckleberry Finn . Young Huck wrestles with whether to embrace the social bigotry of the Antebellum South that is tied to religious dogma and turn his friend, Jim, a runaway slave, in or let him escape. Huck has two choices: either write a letter to Widow Watson (Jim's owner) and have him returned to her, or let Jim run free.

"It was a close place." [he tells us.] "I took [the letter] up, and held it in my hand. I was trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, 'twixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: 'Alright, then, I'll go to hell' — and tore it up ... It was awful thoughts and awful words, but they was said ... and I let them stay said, and never thought no more about reforming. I shoved the whole thing out of my head and said I would take up wickedness again, which was in my line, being brung up to it, and the other warn't. And for a starter I would ... steal Jim out of slavery again ..."

Wheaton College, which was founded by the Huckleberry Finns of its time, has fallen into a version of Antebellum Southern orthodoxy. The question the school's administrators should be asking themselves is whether they will embrace the founding abolitionists' core values or forsake them for the heresy of this new, narrow orthodoxy?

Will Wheaton's administration trade its humanity for a dehumanizing religious construct?

Nostalgia and Regret

Ellison's essay goes on to compare Twain to Ernest Hemingway, who had argued that Twain should have left the morality tale out of Huckleberry Finn and stuck to his stylistic writing. Hemingway said Twain should have had Huck send the letter and return Jim to slavery, because more than likely that's what would have happened in "real' life.

But Ellison explains what that would have left us with if Twain had followed Hemingway's advice:

"Now he is a Huck full of regret and nostalgia, suffering a sense of guilt that fills even his noondays with nightmares, and against which, like a terrified child avoiding the cracks in the sidewalk, he seeks protection through the compulsive minor rituals of his prose."

A few years after my unceremonious departure from Wheaton, the administrators who had kicked me out asked to meet with me separately. We buried our respective hatchets, which was all well and good, but I learned something curious that's stuck with me in the intervening years.

1930059_17713553111_1871_n.jpg

Apparently, the year after I left, the vice president of student development who was instrumental in kicking me out of Wheaton, stopped showing up to work on campus during the last spring semester, which also happened to be his last before retiring.

It turns out that alumni and students had sent aggressive letters, some containing pornography, to the vice president and he was so afraid of another student/faculty uprising in the spring of 1991 that he simply stopped coming to work.

This man clearly was full of regret and nostalgia and as busy avoiding cracks in the sidewalk as Huck might have been had he turned Jim in rather than help him escape the socio-religious constructs of enslaving humanity with the codified stereotypes of slavery.

The great social mythology of Wheaton College, the story that made the school great and unified it around a purpose and values, was that it was built against the entrenched social inequity of slavery. And its founders were willing to commit social evil — by breaking the law to protect fleeing slaves — in order to support human progress.

As slavery ended in the U.S., Wheaton updated this unifying story to be one essentially about evangelism — of going out into the world, to every people, place, and nation to share the Good News, i.e., the Christian Gospel.

The story that made Wheaton truly great was about a God who sent his son to save every single person, slave or free. It was about participating and influencing the world, not removing oneself from it. It most assuredly was not about building ideological or theological walls to protect its students from the enemy (real or imagined). It was about incarnation — God becoming human and walking among us — and in turn, our becoming the hands and feet and voice and love of God in the world.

Creating Monsters to Kill

After World War II, as the world opened up anew, the ideas of Christian fundamentalists who had constructed a new theology around exclusion and isolation, came under attack. Many of its adherents hid under the flaps of evangelical Christianity's big tent and flourished, creating boogeymen based on stereotypes of abstract enemies at war with the culture of conservative, Protestant Christianity.

The fundamentalism that has infected evangelical Christianity with its exclusivist redemption stories and isolating culture, requires invented monsters and fictional battles to survive. It creates the demons it seeks to destroy and gives them tremendous power of the lives of the faithful.

Slaying these imaginary beasts allows Wheaton's administrators and trustees to show their commitment to an orthodoxy that is vital to raising money from conservative benefactors who are busy hiding from the rest of the world. They cling to a version of Christianity that would feel at home in the Antebellum South and praise the return of Jim to his rightful master.

Ellison points out the problem of losing our unifying story, our compelling social mythology:

"For man without myth is Othello with Desdemona gone: chaos descends, faith vanishes and superstitions prowl in the mind ... For it is the creative function of myth to protect the individual from the irrational, and since it is here in the realm of the irrational that, impervious to science, the stereotype grows, we see that the Negro stereotype is really an image of the unorganized, irrational forces of American life, forces through which, by projecting them in forms of images of an easily dominated minority, the white individual seeks to be at home in the vast unknown world of America. Perhaps the object of the stereotype is not so much to crush the Negro as to console the white man."

I don't think Wheaton's administrators were particularly concerned that Professor Hawkins really might be confusing Allah with Elohim, or the Muslim version of Abraham's god with the Christian version. They are the same god of Abraham (a historical fact) and we all agree — including Dr. Hawkins — that Muslims and Christians and Jews understand and worship that god differently.

If Wheaton's administrators truly were concerned with what Hawkins meant, they would have asked her what she meant before they suspended her.

Wheaton's administration and its financial backers who call the shots behind the scenes should not congratulate themselves for having slayed the monster of heresy in their midst, an ideological Fata Morgana that never existed in the first place. But without an organizing myth — a story about a truth bigger than itself — the college's directorate reverts time and again to chaotic superstitions and a fear-fueled bunker mentality.

It needs to create monsters it can kill in order to worship the god it has constructed, a god so small and powerless that Wheaton's trustees and administrators fear ideas different from their own might obscure or even kill it.

My gravest concern is that the school has lost its way. It has lost the organizing social mythology that made it great. Wheaton's leaders today are not the abolitionist founders who fought against dehumanizing social constructs. They are the Hemingways who would send Jim back to Widow Watson.

They create and empower monsters that inhabit their daydreams in a hell on Earth that is as bad as the post-mortem perdition they imagine for those with whom they disagree.

Our role as evangelical Christians is to live the good news and thereby share it with those who are downtrodden and persecuted, marginalized or outcast. We ought to be the first to stand in solidarity with persecuted Muslims, just as Christ himself stood up for Samaritans and the other socially demonized peoples of his day.

Until Wheaton regains a social mythology much bigger than itself, it will continue to react irrationally against imaginary enemies, and in doing so inflict further damage on its community and legacy.

My prayer is that Wheaton College once again will find its moral compass and get back to its Father's business.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!