View the Spanish translation of this article here.

It was only 8 a.m. on a February morning — more than a month before the coronavirus pandemic began affecting daily life — but the crush of bodies augmented the muggy heat in Nuestra Señora de Asunción church in Papantla, Veracruz. When the group of nearly 300 people in matching white T-shirts filed into the front of the sanctuary, some congregants had begun to nod off. The group crowded the yawning nave, turning banners and signs to face the congregation. Hundreds of photos stared out from the signs they held aloft. One by one, three women took to the pulpit to introduce the group. They were the Fifth National Search Brigade in Search of Disappeared People. The photos staring out at the congregation, they explained, depicted their family members: sons, daughters, spouses, parents, siblings, all victims of the forced disappearance crisis in Mexico that has claimed over 61,000 people since the beginning of the country’s drug war.

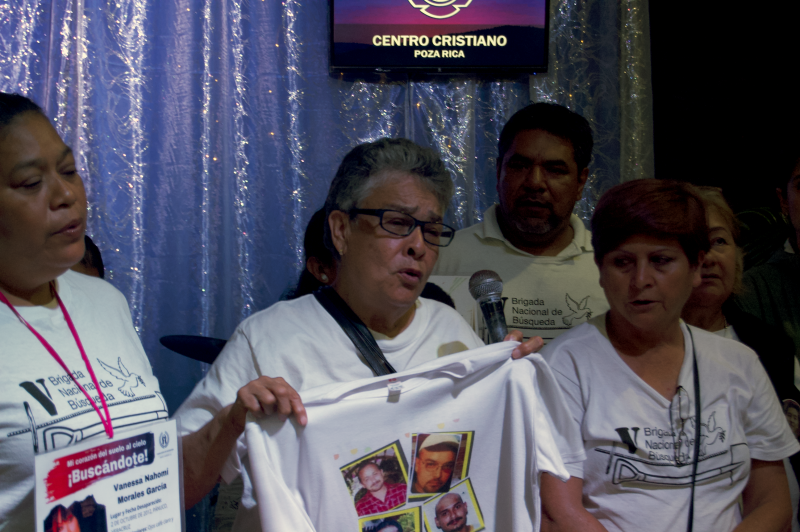

Maria Herrera, a petite woman with deep-set eyes and short-cropped silver hair, ascended to the pulpit to share her story. She had repeated these words thousands of times — and during the next two weeks of the search brigade, she would repeat these words three or four or five times a day, in universities and primary schools, with Catholics and Methodists and evangelicals, to police officers and municipal authorities and journalists.

sojo13.png

“My name is Maria Herrera,” she told the congregation, “and I have four disappeared sons.” She went on to plead for their solidarity: for anyone with information about where the brigade might find clandestine graves to speak out. The brigade, Maria emphasized, doesn’t look for guilty parties. They don’t care about finding out who took their loved ones. They just look for their family members, dead or alive.

“My faith, my trust, is in God. It has always been with him,” she said. “But today I deposit a little bit of that trust in you.”

During a work trip in 2008 to Atoyac, Guerrero, Raul and Jesus Salvador Trujillo Herrera were disappeared, along with five colleagues. At that time, few people were talking about forced disappearance in Mexico, but the crisis had already begun. At the hands of security forces, organized crime, or some combination of the two, people would go missing. Often, their remains would turn up in clandestine graves. Maria and her remaining sons, then in their 20s, started searching. As is common in reporting cases of disappearance, public officials turned her away. She went back and forth from her home in Michoacán to government offices in Mexico City, while her other sons traversed the country, searching for any sign of their brothers. After one of these trips, Maria returned home to find two of her daughters-in-law waiting for her. Luis Armando and Gustavo had also been disappeared.

The four Trujillo Herrera sons count among the tens of thousands of victims of forced disappearance since Mexico’s war on drugs began in 2006. The state routinely covers up or refuses to investigate disappearance; the police and military have been linked to many cases. The government’s refrain around forced disappearances tends to be en algo andaba — they were involved in drug trafficking, organized crime, some sort of illegal activity. More often than not, though, the victims are innocent. The most notorious incident of forced disappearance is the 2014 case of the Ayotzinapa 43, students from a radical teachers’ college who were disappeared after an attack by police. But Ayotzinapa is just the surface. As a senior human rights official put it last year, echoing a refrain of many activists, Mexico is a giant clandestine grave.

sojo1.png

From where I stood in the Papantla church, hoping to catch a breeze near the side door, I looked around to see dozens of women with their eyes filling with tears. The procession filed back out into the streets of Papantla, led by the bishop in his emerald-green vestments. They marched for the next hour through the city, holding up their photos and chanting. Onlookers gathered on the corners; shop owners came to the doorway to watch the crowd pass. “Unete, únete, que tu hijo puede ser,” they chanted — join in, join in, it could be your child.

Many of the 300 people gathered in Papantla were there because of Maria Herrera’s organizing efforts. Along with her sons Juan Carlos and Miguel Trujillo Herrera, she has spent the last decade building a movement of family members of disappeared people in Mexico. Maria has become the most visible face of a movement comprised largely of women like her. They are mothers, wives, and sisters, many from poor rural communities, who never thought about politics until one day their children simply didn’t come home. In the face of government inaction, the families have taken it upon themselves to search for clandestine graves.

Those within the movement refer to Maria Herrera as Mamá Mari. Mari has publicly confronted ex-president Felipe Calderón, who declared Mexico’s war on drugs in 2006, accusing him of responsibility for her sons’ disappearance. She has pushed for the government to search for its disappeared and for the United Nations to intervene in the cases.

The National Search Brigades are one fruit of the Trujillo Herrera family’s labor. During the brigade, family members and activists come together to not only search for clandestine graves, but also lead consciousness-raising workshops and give talks in churches, schools, and other institutions. The 2020 brigade was organized along six areas, or axes, including the church axis. Over the two weeks of this year’s brigade, the group visited dozens of churches to lead workshops, share their stories, and ask others to take action.

This year’s brigade left in place a web of churches committed to the struggle.

“We were able to consolidate a type of ecumenical network,” says Noé Amezcua, who, as part of the Mexico City-based organization Centro de Estudios Ecuménicos (Center for Ecumenical Studies), works closely with the brigade and has facilitated the creation of the church axis, “that would give moral support to the families’ struggles, and support the creation of a local team to continue to raise awareness in churches.” The pandemic has slowed those plans, Amezcua says, but he and other members of the church axis have continued to support the families in Veracruz at a distance.

Constructing A Theology of Disappearance

Mamá Mari is an unlikely activist. She grew up in Pajacuarán, Michoacán, a town of roughly 10,000 in southern Mexico. As a teenager, she came close to becoming a nun. She spent four years preparing with the Operarias de la Sagrada Familia in Zamora, Michoacán, but just before she entered into the novitiate, she decided she didn’t want to give up her independence. As she married and had eight children, she remained a devout believer. When her sons were disappeared, the church was the first place she turned.

“The first people in the house were my priests,” she says. “They came to have dinner, they accompanied me for a long time, they came to pray with me around the table.”

As she began to encounter other families with disappeared relatives, though, Mari began to hear that not everyone received such support from the church. The stigma around disappearance is deep and isolating. Many families of disappeared people face silence not only from government officials, friends, and neighbors, but also from religious leaders. One woman from north of Mexico City told me that when her 16-year-old son was kidnapped in 2016, she went to Mass and asked the priest to say a prayer for him. The priest refused. He was too afraid.

sojo7.png

In that context, Mamá Mari sees the church — with Catholic and Protestant leadership — as a key ally in the fight against forced disappearance. For her, the church’s role in the movement has a dual significance. She wants clergy and laypeople alike to spiritually accompany families of victims. She also wants the church to use its moral authority to speak against disappearance in the political sphere.

“The church has more credibility now than the government,” Mari says. That vision has taken her to meetings with priests, bishops and archbishops, pastors and congregations across Mexico.

Father Arturo Carrasco, an Anglican priest who accompanies a collective of disappearance victims north of Mexico City, believes the church has a responsibility to hold up victims of disappearance.

“The church also tends to believe that disappearance victims are involved in organized crime,” he says. “But the gospel tells us that love casts out fear.”

Sister Paola Clerico, of the Religious of Jesus and Mary, has walked alongside Mari for nearly six years. Paola first met Mari at a march for the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa in late 2014. Since then, Paola has accompanied Maria Herrera and other groups of family members of the disappeared. She says the church has a lot to learn from the family members.

“More than bringing them our theology, it’s about constructing a theology, reading together who God is and how he’s being revealed in our pain,” she says. “With the families, God reveals himself in a really special way, weak, crying, helpless, as the God who searches. He reveals himself as Jesus.”

sojo14.png

That theologizing takes place not in churches, but in marches through the streets of Mexico, outside government offices with unresponsive officials, around clandestine graves uncovered in remote fields.

One day during the brigade, Maria Herrera and Paola Clerico called the searchers together before descending into the day’s site. Shovels and picks in hand, the group joined together in prayer.

“May today be a day of encountering our brothers and sisters,” Paola prayed. The moment ended with a somber squeezing of hands, and the group descended into the brush, where they’d spend the rest of the day searching for human remains of their family members.

Searchers had found dozens of human remains at the site in the past. The property included a house where victims had been kept and a large oven where bodies were believed to have been incinerated. Despite previous searches at the site, the brigade members continued to find bone fragments scattered around the property. As the day went on, members of the brigade began to break down. Their disappeared children and siblings and parents could be in the bone fragments beneath the surface of the soil, in the piles of ash surrounding the oven, in the handprints that marked the walls of the house. Before leaving the site, the group gathered around the oven for a prayer. They stretched their hands over the ash that could include their family members, the opening where their loved ones’ bodies could have passed. They stood in the footsteps of horror, and they mourned. One repeated to another: “Cry, because God is crying today.”

The Via Crucis of Violence

The Mexican church, whether Catholic or Protestant, with exception, isn't known for radically challenging the power of the political status quo. Its political advocacy has often been limited to anti-abortion and LGBT rights. Clergy are often targeted by organized crime, too, and fear can be a factor in avoiding the topic.

“When you say to a priest, we want to come to talk about disappearance, they think twice,” Sr. Paola says. “There isn’t a clear, prophetic voice.”

sojo0.png

Those who speak out about forced disappearance challenge the way the state and criminal groups maintain power through fear and silence. Though the brigade began working within the Catholic Church, it now has allies from a variety of backgrounds. This year marked the first time that the brigade has worked closely with Protestant churches. As in the United States, many evangelical churches in Mexico are often reluctant to join social movements that focus on structural injustices. But the coalition has begun to find allies across the religious spectrum, including evangelicals, Anglicans, and Methodists.

“The church needs to lift up its voice and indicate where there is violence. We need to create a good theology of violence and of peace,” Father Arturo said. “Accompanying this cause is living a constant via crucis.”

A foggy Friday afternoon brought the brigade to a Catholic church in El Rosario, a small village down a weaving road lined with orange trees and cornfields. A few bare bulbs illuminated the sanctuary, its water-stained walls adorned with a graying crucifix, the altar a wooden table covered with an embroidered tablecloth. A few other women stood alongside Maria at the front of the sanctuary, among them Alma Rosa Preciado, from Culiacán, Sinaloa, whose daughter and 2-year-old granddaughter were disappeared in Orizaba, Veracruz in 2012.

Another woman held up the banner of Alma’s daughter and granddaughter, the same photo that Alma has as the wallpaper of her cell phone. Alma broke down in tears as she spoke. As Paola consoled her, a tiny older woman stood up and made her way slowly down the aisle to embrace the two. Throughout the rough wooden pews, no more than a dozen deep, women began to stand. One after the other, they made their way patiently to the front of the church to embrace Alma and Maria and the other mothers. They prayed silently around the growing circle, some silently sobbing themselves. A chant arose from the brigade members, one they echo in moments like these: no estás sola. No estás sola. The words ring through the humble church: “You’re not alone.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!