The first requisite for becoming a photographer is a love of truth. At least according to renowned photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White, the first photographer permitted to explore Soviet Russia’s Five-Year Plan. She seemed to recognize, with all the perspective of an industrial photographer, that truth is multi-sided and difficult, but imperative to capture.

When she was faced with the challenge of showing the whole truth about the dictator Joseph Stalin, she photographed his mother. She took her historical invitation into Soviet territory seriously and passionately, bringing 600 pounds of equipment across 5,000 miles of Soviet territory.

Margaret Bourke-White was not scared of heights. Walking out on a ledge to take a picture of dam-fortifier or construction worker was bold, but not enough. So she zoomed in on the priest, solemn and avoiding eye contact during a time when the state banned formal religious practice. Truth was the tension between the awe-inspiring building projects and the social and human collateral damage.

Bourke-White traveled the world in search of complete stories: from Depression-era Hooverville to partitioning India to Apartheid in South Africa to Nazi Germany. She became the first female war photojournalist and the first photographer for LIFE. After surviving a helicopter crash and getting stranded in the Arctic, Bourke-White’s colleagues declared her “Maggie the Indestructible.”

She would need this impassable armor on both a physical and emotional level during her trips through Germany. Bourke-White and her colleagues documented the liberation of the Buchenwald Nazi concentration camp in April 1945. Her most famous photo from the trip was one of starving men staring at the liberators and the camera with bewilderment. In other photographs, it’s hard to tell the difference between who is alive and who has passed.

2453488543_7b318f0e71_o.jpg

These photos are almost unbearable, which is why they were so needed. When LIFE published Bourke-White’s photos, they exposed the truth to a world who would not or could not believe the truly hellish nature of the concentration camps.

One of Bourke-White’s photos viscerally and disturbingly captures this longing for ignorance. American soldiers forced residents from the nearby German town to see their backyard atrocities for themselves. Bourke-White snapped a shot of a young German girl shielding her eyes as she walked by a pile of corpses. Sometimes we must see it to believe it. Bourke-White refused to let history shield itself from its most unimaginable sins.

This was a lot for Bourke-White to carry. In her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, she explained that the only way for her to make this work sustainable was to foster an inner tranquility. “I had picked a life that dealt with excitement, tragedy, mass calamities, human triumphs, and suffering. To throw my whole self into recording and attempting to understand these things, I needed an inner serenity as a kind of balance.”

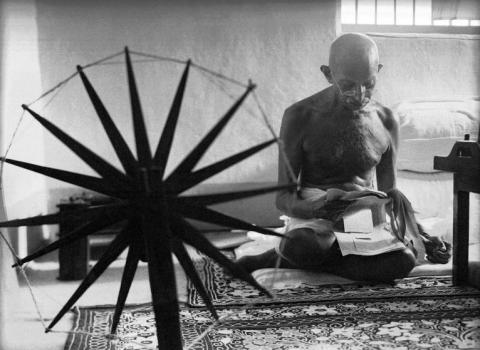

After years of flying with U.S. combat crews and accompanying generals on military missions, Bourke-White had the opportunity to thoroughly get to know Mohandas Gandhi, India’s meek champion of nonviolence action. Though she wrote of disagreeing with Gandhi in some areas, Bourke-White came to have a deep respect for him.

“I had seen men die on the battlefield for what they believed in, but I had never seen anything like this: one Christ-like man giving his life to bring unity to his people.”

Bourke-White took a beautiful portrait of Gandhi just hours before his assassination — the last and potentially most famous photo ever taken of him. In the portrait, Gandhi sits behind his spinning wheel, silently reading the news. Time selected “Gandhi and the Spinning Wheel” as one of the “100 Most Influential Images of All Time.” Only eight photos by women made the list; Bourke-White shot two of them.

gandhi-spinning-wheel-01.jpg

Bourke-White was a photographer and writer who committed her life to telling the whole story for the betterment of a history that had largely excluded women from its telling, let alone its plot. Just as truth ought to be a requisite to photography, women like Maggie the Indestructible should be requisite characters to history, on women’s history month, and every month.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!