Gareth Higgins (garethhiggins.net) is a writer and broadcaster from Belfast, Northern Ireland, who has worked as an academic and activist. He is the author of Cinematic States: America in 50 Movies and How Movies Helped Save My Soul: Finding Spiritual Fingerprints in Culturally Significant Films. He blogs at www.godisnotelsewhere.wordpress.com and co-presents “The Film Talk” podcast with Jett Loe at www.thefilmtalk.com. He is also a Sojourners contributing editor. Originally from Northern Ireland, he lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

Posts By This Author

Trials and Tribulations

THE EXTRAORDINARY film Leviathan takes place in a tiny coastal town on the other side of the world, but it relates to all our dreams and fears.

A man is tormented by bureaucracy, as the authorities try to take his house. He has an unhealthy relationship with alcohol, and a very unhealthy one with his partner. He works on people’s cars, does favors for people who ask him, and tries to raise his son as best he can. And he’s caught between the wheels of historic oppression and emerging forms.

Leviathan, this year’s Russian nominee for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, is a work of uncommon cinematic bravery, for the people who made it take on the corruption of their current political masters. Vladimir Putin appears briefly, as a portrait looming over the office of the mayor trying to take our hero’s house. But the graft, selfishness, and cruelty of Putin’s imperial reign are palpably present in the mayor, who has been fighting the householder for years to get his property, for reasons that owe more than a little to the legacy of Soviet-era patriotic ideology. Communism has been replaced by a heady mix of nationalistic pride and elitism religion, whose boundaries are enforced with no mercy. Pussy Riot’s punk prayer gets a mention in a priest’s litany of things that are undermining Mother Russia. It’s the same old story, there and everywhere—keep the nation pure, confuse spirit and law, and wreck your own life by denying the glories of human diversity.

A Newsfeed of Fear

I GREW UP terrified, my childhood catechized by the violence in Northern Ireland, each week a litany of murder. I grew used to the idea that killing was the story of our lives. This, of course, was not true—there was also beauty and friendship all around us, all the time, not to mention eventually a peace process that has delivered extraordinary cooperation between former sworn enemies.

But the way we learned to tell the story—from political and cultural leaders, religion, and the media—emphasized the darkness. It’s been a long and still ongoing journey for me to discern how to honor real suffering while overcoming the lie that things are getting worse.

Today, many of us are living with a fear that seems hard to shake. Horrifying, brutal videos, edited for maximum sinister impact, showing up in our newsfeeds are only the most recent example of how terror seems to blend into our everyday lives.

But things are not as bad as we think. What social scientists call the “availability heuristic” helps explain why we humans find it difficult to accurately predict probability. In short, we guess the likelihood of something happening based on how easily we can recall examples of something similar having happened before. Because of this, folk who get a lot of “information” from mainstream media may tend to overestimate the murder rate: Most of us have seen vastly more killing on TV than would ever compute to an accurate estimate of real-world rates of killing.

Shooting in a Moral Vacuum

CLINT EASTWOOD has made films about the sorrow and repeating pointlessness of war, as seen through the eyes of both aggressor and aggressed-against, with empathic performances and unbearably moving impact. His American Sniper, about the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, bloodied in Iraq and struggling at home, is not one of those films. At best it’s a valuable character study of a confused warrior, revealing the traumatic effect of his service. At worst it’s a jingoistic and xenophobic attempt to put varnish on a terrible national response to the horror of 9/11, a response that became a self-inflicted wound creating untold collateral damage.

A decade ago, Eastwood made Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, which saw World War II soldiers as propaganda fodder and had the moral imagination to show both sides as courageous and broken without denying the difference between attacker and defender. These films are respectful and thoughtful, but American Sniper is arguably a work born in vengeance. Its reception (becoming one of the biggest January box office weekends ever, and a quick right-wing favorite) is part of the failure to deal in an integrated way with the wounds of 9/11, or to even begin to face the reality of the war in Iraq: an imperial conquest using the cover of national trauma as a justification

Moved, or Moved to Act?

FOR TWO YEARS in a row we have seen significant films about oppression and struggle nurture public consciousness. Selma and 12 Years a Slave invite us to reimagine iconic moments closer than we usually think, their protagonists more like us. Slavery had not been portrayed in such visceral fashion in a mainstream film before 12 Years. Before Selma, images of Martin Luther King Jr. had never quite transcended the almost superhuman projections that accrue from his martyrdom and decades of being co-opted by cultural mavens from Apple to Glenn Beck.

These films create new benchmarks for the mainstream depiction of black history, black struggle, and wider perceptions. But entertaining portrayals of inspiration contain a powerfully dangerous substance that needs to be handled with care. The cathartic tears shed at a film about other people’s suffering and heroism can also be a narcotic, implying that the work has been done. Think of all the talk about freedom struggles after Braveheart, or challenging the principalities and powers after The Matrix. The problem was, most of it was just that. Talk.

A Year of Great Films

THIS PAST MOVIE year I’ve been delighted by, among other things, nonviolent resolutions, a guy talking in a car, an Irish priest trying to do the right thing, and a five-dimensional bookcase. Here’s my list of the 10 best films of 2014 (many more are worthy, but 10 are all that will fit).

10. Pride. A delightful and stirring celebration of marginalized people turning their woundedness into helping others, as LGBTQ activists support the Thatcher-era British coal miners’ strike.

9. The Lego Movie. This turned out to be both the most unpredictably fun and one of the wisest films of the year. A brilliant critique of consumerism and political tyranny, with an ending that inverts the myth of redemptive violence.

A Better Kind of Good

TOOTSIE, the 1982 Dustin Hoffman comedy in which a failing actor cross-dresses to win a part on a soap opera, is a lovely, problematic film (and just released in an excellent home edition from www.criterion.com). It’s controversial in some quarters for playing the idea of a man dressing as a woman for laughs: The joke is on any male-bodied person who challenges macho stereotypes. As when The Da Vinci Code attracted criticism for portraying a character with albinism as an insane assassin, like almost every other comparable movie has treated albinism, Tootsie represents a time when the extent of mainstream cinema’s engagement with what it thought constituted “trans” was to portray cross-dressing for laughs. But a cisgender straight character dressing up has little or nothing to do with the real stories of the “T” in LGBTQ.

Cinematic LGBTQ characters seem to evolve one step forward and a half back—beginning with their invisibility, then moving through psychopathy (the “evil queer” of Hitchcock’s Rope still shows up in The Lion King and The Avengers); martyrdom (Kiss of the Spiderwoman, Philadelphia, Brokeback Mountain); safe best friends (The Prince of Tides and My Best Friend’s Wedding); and eventually redemption (Milk, the wonderful recent Pride). The evolution continues: George Carlin’s gay best friend caricature in The Prince of Tides was in good faith, but would not pass muster today. We’re shaking off the idea that LGBTQ characters can only be suffering or sassy.

A Culture War Misfire

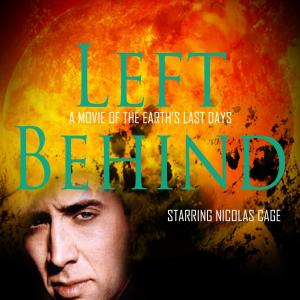

LEFT BEHIND may be a soft target, but once seen, you may realize that it’s a soft target for anyone who has ever been on an airplane, seen what Nicolas Cage is capable of in Leaving Las Vegas, met a Muslim, or not been cryogenically frozen since the era when it was socially acceptable to treat people with dwarfism as punchlines.

It really is worse than most theatrically released movies—shot and edited like a political attack ad/music video mashup, written like a child’s Sunday school lesson, and then strangely denuded of almost anything that would make it identifiably Christian (teasing those who already believe, yet scared of alienating people who just want to see a cheesy disaster movie without heavy proselytization).

The people who made it aren’t bad people, of course. (I’m not sure anyone is, with the line between good and evil running through each human heart and all—although that’s another argument that wouldn’t make it into this film.) The producers are ideologically committed to advancing a message that they were indoctrinated into by an unthinking system—let’s call it the Christian Industrial Entertainment Complex. They’ve stumbled upon the money and basic skill to make movies. They think that what they’re doing is changing the world for the better, but that’s doubtful—it’s more likely just reinforcing the closed-set worldview of the CIEC’s pre-committed adherents. This isn’t new, so I’m not too concerned about one more example of bad art masquerading as religious experience.

Boomtown Stories

HIGHBROW FILM criticism and fanboy comment pages alike often manifest as if their purpose is to make snarky points about who knows how much about what. Whether in an academic journal or on Reddit, film criticism can either get the point or be the point. We can either convince ourselves that we exist to show the world how smart we (think we) are—or to facilitate a conversation about the purpose of art that’s spacious enough to stimulate both the heart and the mind.

The lack of clarity about such purpose means that it has to be continually reasserted, so here goes: The purpose of art is to help us live better. I contend that this is the primary evaluative lens through which we should watch. Of course aesthetics, craft, and content matter, but how I watch films depends at least as much on the notion that art emerges from a human creative impulse that is at its best directed at the common good.

The protagonist of the new documentary The Overnighters has made a similar shift in consciousness regarding his own vocation. North Dakota pastor Jay Reinke understands that the purpose of church isn’t far different from that of art, and he opens his building to economically disenfranchised folk trying to find a job in the oil boom, letting them stay overnight despite local suspicions. It’s a manifestation of Christian vocation mingled with lightly ringing alarm bells—the pastor appears to be a Lone Ranger, not collaborating with supportive church leaders or members; the jobs are in an environmentally degrading industry—and a picture of community service that seems at once miraculous and exhausting.

Possible Grace

WHAT’S A GOOD priest for? So asks Calvary, the second feature film from writer-director John Michael McDonagh, rooting itself in Ireland’s coastal landscape, centering on a pastor threatened with scapegoat-retributive murder from a grievously sinned-against parishioner. Its vibe owes a great deal to the quiet reflection of films such as Jesus of Montreal and Au Hasard Balthazar (in which a donkey evokes the love and wounds of Christ), and the archetypal Westerns High Noon and Unforgiven. Brendan Gleeson plays a priest who was drawn into the church after his wife’s death, which allows us the rare experience of seeing a cinematic Catholic priest who is both a parent to his flock and to a beloved daughter, who feels somewhat abandoned by his commitment to the church.

Gleeson has the uncanny ability to hold his massive frame as both solid—almost concrete—and vulnerable. Knowing that everyone is both broken and breaker, his Father James is healing on behalf of a flawed institution, although he doesn’t confuse vocation with a job. His bishop’s response to a request for help is “I’m not saying anything,” reminding me of Daniel Berrigan’s challenge to religious hierarchies, heard at a public meeting in Dublin in the run-up to the Iraq war: “In Vietnam, they had nothing to say, and said nothing; now, they have nothing to say, and they’re saying it.”

Father James understands the difference between stewarding power and grabbing it (one obvious signal of his goodness), and he is up to his neck in the community, running the gamut from friendship with an American writer looking for inspiration in the land of his presumed ancestors to a visit with a former pupil whose own inner darkness has led him to do monstrous things.

Small Screen, Great Drama

IT’S A TRUISM to say that television is outpacing cinema for entertainment quality and depth of exploration. Since The Wire appeared a decade ago, studios have been realizing that there is an audience for long-form storytelling that is willing to think.

Recently I’ve been struck by the set-in-the-’80s espionage thriller The Americans, the deeply haunting police procedural True Detective, the hilarious pathos of Louie and Veep, and the sly, shocking Hannibal, a prequel to The Silence of the Lambs: All hugely entertaining, dramatically credible, and challenging both as works that require sustained attention and in terms of what they say about life. The Americans is really an exploration of marriage and cultural identity wrapped up in Cold War cloaks-and-daggers; True Detective is a lament for the broken parts of America, and an affirmation that friendship endures above almost everything else; and Hannibal is a postmodern delving into Dante’s Inferno, looking at the underbelly of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s assertion that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What’s most exciting is that it’s now considered viable to make drama that actually asks real questions about life and is prepared not to answer them pat. Along with the vast amount of social media conversation about these works, what we have is more akin to ancient forms of public entertainment that required a kind of audience participation—theatrical catharsis meeting gathered conversation to produce a community hermeneutic. When we talk about TV and cinema, we’re talking about ourselves.

Viewing Community

THERE ARE apparently 2,000 film festivals around the world, so the format of red carpet arrivals, gala screenings, and Q&A sessions that appear all but scripted in advance have become well and truly entrenched. The best festivals recognize that their purpose is to cast a spell over filmgoers and filmmakers alike, inviting them into a spacious place where the heart of the dream that led to the film being made and the audience’s reason for watching it can beat in a community of people who thirst for art that gives life. Unsurprisingly, the biggest festivals find it hardest to pull this off—asking for contemplative mutuality at Cannes or Sundance is like looking for a Buddhist tea garden at Disney World.

Yet film festivals can be places where small is indeed beautiful. It’s only the movies that need to be big—or at least their capacity to alchemize with the viewer’s autobiographical narrative. The trappings of VIP lounges, paparazzi, and celebrity gossip are just that: They trap the aesthetic air, creating distance between people and art. Smaller festivals may be more capable of nurturing something that really feels like community.

So when at North Carolina’s Full Frame Documentary Film Festival this spring we watched Visitors, Godfrey Reggio’s follow-up to his epochal Qatsi trilogy, and the diverse faces of human beings segued into natural landscape and a Louisiana cemetery, the sense of empathic connection with an artist who spent the first 14 years of his life in New Orleans and the next 14 as a Christian Brothers monk was palpable. The impossible-to-categorize musician Nick Cave portrayed a sly version of himself in the pseudo-documentary 20,000 Days on Earth, intercutting concert footage with a role-played therapy session, visits with friends, and a neo-noir road trip, to moving effect. And the gay rights courtroom drama of The Case Against 8 played to an audience of citizens whose state had adopted a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage; the showing led to near-euphoric anticipation of how a better history can reverse this tide.

Security State Superheroes

THE CLASSIC COMIC book hero is given a post-WikiLeaks spin in the film Captain America: The Winter Soldier. He realizes that he is being asked to participate in the extrajudicial killing of people whom a magic formula has decided might threaten the established order in the future. It’s intriguing that even Nick Fury, one of Captain America’s “bosses” at the superhero super-agency S.H.I.E.L.D. (lines of authority are never particularly clear when super powers are in play), almost goes along with this.

To build a new world, sometimes you have to tear the old one down, says character Alexander Pierce, played by Robert Redford in a role that both echoes and inverts the ones he often took in the ’70s—where, in films such as All the President’s Men and Three Days of the Condor, he fought the system from within for good. This time Redford’s having fun as a bad guy, while Captain America (aka Steve Rogers) is the golden boy flirting with the audience and inviting us into his subversive politics (indeed the first words he speaks—the first words of the movie—are “on your left”).

So The Winter Soldier is striving for far more than your typical comic book movie and has been clearly influenced by the Dark Knighttrilogy in aiming for philosophical depth. There are interesting ideas here—S.H.I.E.L.D. being part of the problem and the character Winter Soldier’s name evoking the 1972 documentary Winter Soldier about Vietnam vets expressing regret. There are fun bits of business with Steve Rogers’ difficulties in adjusting to the contemporary world (such as the dawning reality that Star Wars andStar Trek are different things). And there’s real character development, especially in Rogers’ interactions with the Black Widow.

If I Were a Rich Man

BEST-SELLING WRITER James Patterson recently established a million-dollar fund to support independent bookstores amid the current publishing industry crisis. Patterson is showing both generosity of spirit and humility before the audience that made him rich, not to mention an ethical commitment to the community-building impact and personal pleasures of smaller bookshops.

I think his open-minded and visionary idea should be translated to independent theaters too. The experience of entering shopping mall multiplexes to be seated in a shoebox and watch 25 minutes of advertisements before the same film that’s screening at every other multiplex does not resonate with the poetics of the art. And I mean that literally—beautiful cinema does not belong in an ugly industrial container. I mean “belong” literally too—if art is about belonging, about the idea of finding a home for our idea of ourselves, then it would make more sense to screen movies in environments that invite a sense of home, not evoke battery farms.

If James Patterson were to set up another million-dollar fund devoted to independent movie theaters, I’d be happy to help him spend it. I’d upgrade projection, audio, and lighting so that as much attention can be paid to how a film looks as to how paintings are hung in a gallery or music played in a concert. I’d make the seats comfortable for average-sized human beings. I’d give grants to community groups who want to refurbish their dilapidated downtown theater as a venue for the common good. I’d screen films that invite social change. I’d develop new distribution networks that challenge the dominance of the military-industrial-entertainment complex—offering the rights to screen films in exchange for an ethical fee or a gift in-kind. I’d have potlucks at 5:30 p.m. and movies at 6:30 p.m. so there’s enough time afterward to write poetry together or march on the capitol.

Cine-Monastic Disciplines

ONE OF THE paradoxes of writing about film is the application of one form of language to interpret another. The medium we’re discussing here is visual, and despite the relevance of the word “poetic” to the great works of cinema, to interact with the movies means, as writer-director John Sayles says, to “think in pictures.” In an age with multiple ways to consume films, and the pressure to respond with the immediacy of social media, to think deeply about movies is a countercultural act.

I noticed this again after being given a record player a few weeks ago. I’ve listened to Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks more than pretty much any other album over the past 20 years and now on the vinyl recording I can actually hear instruments I’d never noticed before. I can’t deny the superiority of the medium, at least in terms of what we might call “musical richness.” But digital transmission makes the sound crisper and more available.

There’s a parallel paradox with cinema, in that the experience of watching films has both diminished and expanded over most of our lifetimes. There are more portals than ever (you can watch Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story or Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo on your phone, for goodness’ sake). Yet the opportunity to see films in optimal settings (decent projection, focused audience, without 25 minutes of commercials for soda mingling with threats of prosecution directed at the people who have paid to see the film by the industrial complex that depends on them) doesn’t come often for most of us. Without conscious resistance, the flattened culture of entertainment globalization is going to continue to dominate.

Not Afraid of the Dark

INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS, the new Coen brothers film, is the mournful tale of a folk musician too dedicated to his art to make money or to accept love when it’s offered him. It has gorgeous music, performances that are like watching characters step off the pages of a Joseph Mitchell New Yorker story, and language that is exquisite, but not so much that we don’t believe it. A common response to Inside Llewyn Davis is that it’s a pessimistic film, with characters so self-centered and worn down by money and the lack thereof that they cumulatively produce a world of no hope.

Many assert that the Coen brothers have pitched their tent as the anchor tenants of cinematic melancholia—Fargo’s bleak focus is a family utterly destroyed by financial pressures and the inability to know where or how to ask for help; Barton Fink’s eponymous protagonist finds his dream writing contract ends up a descent into hell; and The Man Who Wasn’t There is finally executed because he doesn’t see the point in defending himself. Llewyn Davis is an impetuous man in a fickle industry, too out of touch with his own humanity to want to see his own child, and he is beaten up for heckling a fellow musician. And so people come out of this film depressed. To which my minority response is simple: Look closer. Inside Llewyn Davis is full of life and second chances and, yes, hope for artists. Davis has friends who care, and there are people who get what he does. Who cares if the world isn’t listening? That was never a measure of great art anyway.

States of Being

I’VE RECENTLY spent time researching the vision of the U.S. through the lens of one film for every state, following the intuition that, as most movies are set in Southern California or New York (and there’s a lot more America where those didn’t come from), we need to examine Fight Club and On the Waterfront, Brokeback Mountain and Nashville no less than The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind to begin to capture the American dream life. It seems obvious, but it’s often dismissed: Contrasts between the states are mighty and rich. A Wyoming plain and a Sonoma vineyard, Hoboken and Harlem and Hot Springs, the Florida Keys and the Swannanoa Valley are all magnificent intersections of dreams and mistakes, which in honest art allows them to be places where the past can be faced.

And on that note, here’s my list of the 10 best U.S. films released in 2013:

The new Criterion Blu-ray John Cassavetes box set includes The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, the best entry to his work: A grimy thriller about one man trying to make art against the odds.

Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez show us something more of how to be human in Fearless (newly available on Blu-ray), about a man who needs to die before he can live (and love).

Missed Reckonings

THE MOST common image of the assassination of President Kennedy is embedded in the collective consciousness due to the fact that it was the subject of what may be the most-seen film in history, Abraham Zapruder’s 26-second home movie, grainy and garish in color and fact. The more recent eruption of reality television may have left us nearly unshockable, but a long, hard look at Zapruder’s short, hard film is still horrifying. The most provocative context in which I’ve seen the film located is Stephen Sondheim’s meaty musical Assassins. The Broadway production had Neil Patrick Harris as Lee Harvey Oswald with the film projected onto his white T-shirt. That the show took place at Studio 54 served to underline the demonic bargain at the intersection of the military-industrial-circus complex: The nightclub theater location satirized the fact that our stories about killing can either critique the cultural appetite for destruction or serve to perpetuate more of it as a form of entertainment.

If Assassins was the most provocative screen for the Zapruder film, the most politically complex is Oliver Stone’s 1991 movie JFK, now being rereleased to mark the assassination anniversary. It’s one of the greatest examples of cinematic craft applied to polemic (current examples are Captain Phillips and 12 Years a Slave)—edited like a dance, with a television miniseries’ worth of big name actors (Jack Lemmon, Sissy Spacek, Walter Matthau, Donald Sutherland, John Candy) in small roles holding up the edifice of big speechifying done by Kevin Costner and Tommy Lee Jones. It’s a thrilling film, and it has intellectual substance—the point is not whether or not the conspiracy theory posited in JFK is true, but that human beings “sin by silence” when we should speak.

Making Once Enough

I RECENTLY saw a photograph of me taken on the day I was born: two weeks premature, swaddled, peaceful, vulnerable, beautiful—pure potential. I wanted to travel back in time to give the little guy some advice and protect him. Most of all I wanted him to experience the things I missed—those that only seem to come to our attention with the benefit of hindsight. I wanted him to take more risks for the good, not worry so much, be more open to receiving love, take more walks in fields and on beaches, and avoid a thousand mistakes. I wanted him to be different.

While wanting to undo history is probably a human universal, it can also be a kind of psychic violence, emerging from the notion that there is such a thing as the person we were “supposed” to be. Indulging this notion led to me projecting it onto three intriguing films. Short Term 12 is a lovely, painful story of recovery from childhood wounds. In Seconds, the newly restored melancholic science fiction tale of human engineering from 1966, Rock Hudson brilliantly imagines what happens when you convince yourself that superficiality is depth and exchange the life you have for cosmetic “transformation.”

Complexities of Struggle and Love

LEE DANIELS’ The Butler, a century-spanning tale of race in the United States and service in the White House, is a dream of a film—by turns historically realistic and magically fable-like. It’s a perfect companion piece to last year’s Django Unchained, in that case a movie whose tastelessness wrapped up as fabulous entertainment forced audiences to engage with a deeper level of the shadow of U.S. history.

Based on the story of Eugene Allen, a black man who served multiple presidents in a White House that took its own time to desegregate its economic policies for domestic staff, The Butler begins with a rape and a murder of plantation workers by the son of the boss. The ethical quality of the film is immediately apparent. This horror is not played for sentiment, nor even spectacle, but to evoke the very ordinariness of monstrosity.

This makes The Butler a rare film: one more interested in confronting us with a kind of previously unspoken truth than in goading us to feel the catharsis of guilt-salving by association. (It’s the antithesis of films such as Mississippi Burning, which use white protagonists to tell black stories and appear to believe that we can somehow participate in the virtue of the civil rights movement just by watching a movie about it.) The makers of The Butler have told a kind of truth about the struggle for “beloved community” that has rarely been seen so clearly on multiplex screens. The film illustrates the serious and painful work of nonviolence and invites us to consider the political and cultural tensions within the black freedom struggle, while giving a more humane perspective on the presidency than is often the case. We can hope the door is now open to more reflective cinema about the unfinished business of the black civil rights movement, broken relationships, traumatic memory, and how we tell the story of who we are.

Meditating on Memory

CINEMA IS poetry, not prose, and so looking for “realism” in movies is an ambiguous task. Perhaps the better comparison would be with memory, for the way we experience the past might feel a little bit like a film unspooling in a low-lit room, the images urging themselves onto a wall with frayed paper, red-hued, with the sound fading as I get older. Like the opening of the film of Carl Sagan’s novel Contact in reverse, in which all the radio signals that have ever been broadcast speak their way into deep space, the further away I get from a memory, the more like an old movie it seems.

The role that cinema plays in memorializing the past is unparalleled—for both the way we experience memory and the memories themselves are uniquely bound up in each other—Casablanca or There’s Something About Mary alike may remind us of past loves, and perhaps also of the time and place we saw those movies, and watching either of them again enables us to re-experience the very emotions we may have first experienced by watching it. When we experience movies like memories, we meditate rather than consume, and do what Pascal suggested was the antidote to all the problems in the world: sitting still for 10 minutes and thinking. At the cinema we take a walk in our minds and, through an art form that is usually less controllable than reading or listening, we are taken somewhere new.