Julie has been a member of the Sojourners magazine editorial staff since 1990. For the last several years she has edited the award-winning Culture Watch section of the magazine. In her time at Sojourners she has written about a wide variety of political and cultural topics, from the abortion debate to the working class blues. She has coordinated in-depth coverage of Flannery O’Connor, campaign finance reform, Howard Thurman, the labor movement, and much more.

She studied English literature at Ohio State University and has an M.T.S. (focused on language and narrative theology) from Boston University and an M.F.A. in creative nonfiction from George Mason University.

Julie grew up on a farm in the northwest corner of Ohio. She has been fascinated by the power of religious expression in and through culture since she can remember. Obsessively listening to her older sister’s copy of the Jesus Christ Superstar cast recording when she was 10 was an especially crystallizing experience. In addition, Julie’s mother often argued about doctrine and the Bible and took her at least weekly to the public library, both of which were useful background for Julie’s current work.

She lives in the Columbia Heights neighborhood of Washington, D.C. and is a member of St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church (where she had an unlikely four-year reign as rummage sale czarina). Her personal interests overlap nicely with her professional ones: Music, books, reading entertainment, culture, and religion writing, art, architecture, TV, films, and knowing more celebrity gossip than is probably wise or healthy. To make up for all that screen time, she tries to grow things, hike occasionally, and wonder often at the night sky.

Some Sojourners articles by Julie Polter:

Replacing Songs with Silence

Censorship, banning, blacklists: What’s lost when governments stifle musical expression?

Extreme Community

A glimpse of grace and abundance from - of all things - reality TV.

The Cold Reaches of Heaven

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Bill Phillips talks about his faith.

Just Stop It

Daring to believe in a life without logos. An interview with journalist Naomi Klein.

Women and Children First

Developing a common agenda to make abortion rare.

Obliged to See God (on Flannery O’Connor)

Posts By This Author

From Stage to Page

JUDITH CASSELBERRY'S ORIGINAL LOVE WAS MUSIC. She has been a guitarist and vocalist her entire adult life, including a 1980 to 1994 stint as part of the duo Casselberry-DuPreé. She now performs with Toshi Reagon and BIGLovely. She has shared the stage with Sweet Honey in the Rock, Odetta, Stevie Wonder, Etta James, and Elvis Costello, among others.

Along the way, while still performing, Casselberry earned her bachelor’s degree (in music production and engineering) and then, a few years later, a master’s in ethnomusicology, during which she discovered a passion for teaching. So she went to Yale, earning a doctorate in African-American studies and anthropology in 2008. She is an associate professor of Africana studies at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, teaching courses on African-American women’s religious lives, music and spirituality in popular culture, music and social movements, and issues in black intellectual thought.

Casselberry’s forthcoming book, The Labor of Faith: Gender and Power in Black Apostolic Pentecostalism (Duke University Press), employs feminist labor theories to examine the spiritual, material, social, and organizational work of women in a New York-based Pentecostal denomination, Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ of the Apostolic Faith (COOLJC). In the course of her research, Casselberry immersed herself for more than two years in the life of True Deliverance Church in Queens, N.Y. She spoke by phone with Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter in late January.

Sojourners: You examine the “religious work” of women—including prayer, teaching, care for the sick and grieving, liturgical music and movement, and guiding converts. Why did you choose this framework?

The Resurrection of ‘Jesus’

My obsessive inner nerd rose to attention. You couldn’t have seen resurrection in Jesus Christ Superstar because there was no resurrection in Jesus Christ Superstar. That was the point! [I online shouted.] That’s why some considered it scandalous — a very human Jesus, a Judas who makes a lot of sense if you listen to him, and no Jesus rising from the dead. It doesn’t deny the resurrection. It just stops beforehand

Myths and Migrants

Tisha M. Rajendra discusses her new book, Migrants and Citizens: Justice and Responsibility in the Ethics of Immigration (Eerdmans), with Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter.

The Bible According to an Oversized Book of Cartoons

IT HAS BEEN A TIME of shadows and warnings, bursts of violence and the creeping stain of betrayal. Falsehoods, at first a dripping faucet over a tin bucket—the hint of failing seals and valves, the promise of future corrosion—have become a downpour. Disintegration seems the rule.

Where to find a true story, one that endures?

Scripture might seem the logical turn for a Christian. But I know my weaknesses. Left to my own devices, I cherry-pick favorite verses, I swerve away from difficult passages. I rarely read anything in the Old Testament except the prophets—and those while too often presuming I stand with them, already on their side, and God’s: Nothing for me to hear, except the echo of the woe and correction I’d like to dole out to others. A situational loss of hearing that is a sure path to perdition.

But then I was introduced to an unusual portal to the holy word, one that easily charmed its way past my conscious and unconscious scriptural biases: a 500-plus-page coffee-table book whose bronze cover is adorned with line drawings of people who are at turns winsome and ominous. With title and highlights in fluorescent orange, the design is reminiscent of some DayGlo-kissed whimsy from the 1960s. In the Beginning: Illustrated Stories from the Old Testament (Chronicle Books) retells, through images and spare prose that is both fresh and respectful of the scriptural sources, core stories of the Judeo-Christian tradition, from creation and the Garden of Eden to Daniel in the lions’ den.

Business and the Gospel of Enough

JoAnn Flett decided at a young age that she loved both spreadsheets and Jesus. After more than 20 years of senior accounting and management experience, she now directs the masters in business administration program at Eastern University, a theologically informed curriculum with a strong sense of social justice that equips students with business acumen to serve God and society through business. She sat with Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter in June to tell her story.—The Editors

When we think of the church and business, we tend to think of them at opposite ends of a spectrum. We often think of businesspeople as a certain kind of person, one that doesn’t conjure up the best images of humanity.

I was privileged, early on, to have friends who were very successful business leaders. What drew me to them was that they were people whose faith mattered to them; they led their organizations without making a big fanfare about this, but they were leading from a faith perspective.

I admired that they ran successful companies that transformed their employees, their business partners, and their local communities. But nobody seemed to celebrate them in their local churches. It’s easy to think of teachers and nurses, people in the “helping professions,” as doing God’s work. Yet there are people of faith who lead powerful and influential organizations. These people go to work and make critical decisions, and their faith has all kinds of implications about how they live in the world, but their work is not being affirmed on Sunday.

The Murder That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement

ON A HIGH PLATFORM in the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., sits a glass-topped casket. The museum’s deputy director, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, has called it “one of our most sacred objects.”

The casket once held the body of 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African-American boy from Chicago who, while visiting family in Mississippi in the summer of 1955, reportedly whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant at a country store. A few nights later her husband and brother-in-law kidnapped Till, beating and murdering him before fastening a heavy industrial fan to his neck with wire and throwing the body into the Tallahatchie River. The local sheriff ordered Till’s body to be buried the same day it was found. Instead, one of Till’s great uncles intervened and made sure the body was returned to his mother in Chicago.

Mamie Till-Mobley allowed photographers from Jet and Ebony magazines to take pictures of Till’s mutilated face and insisted on an open casket and public viewings. Tens of thousands filed by Till’s broken body.

25 Books in Our Resistance Library

I asked colleagues here at Sojourners: What books would be in your resistance library? Their top 25 suggestions are below. Use the hashtag #MyResistanceLibrary to track our reads — and share to let us know what you’d add to the list!

10 Children's Books That Celebrate Our Diverse World

Where do we find quality stories for children about a diverse world? Not books that preach, but that evoke empathy and curiosity and different perspectives through good stories and/or art? As is the case across all publishing categories, books by and about people of color (or people who are not able-bodied or citizens or middle-class or otherwise conforming to a mainstream standard) are in the minority.

Better Together

DURING A FRACTIOUS election year marked by “how low can you go?” rhetoric, a hopeful word about democracy can be hard to find. When our civil society and citizenry seem evermore splintered by issues of race, immigration, wealth inequality, women’s health, guns, and ideology, who would dare speak with sincerity about finding common cause and increasing enfranchisement?

Rev. William Barber II, for one. In The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics, and the Rise of a New Justice Movement, he argues that “fusion coalitions rooted in moral dissent have power to transform our world from the grassroots community up.” He believes that people committed to different causes, of different races and faiths and no faith, can come together to advance broader justice and perhaps even revive a democracy that has seen better days.

He believes this because he’s seen it: He helped forge the 2013 “Moral Mondays” protests in North Carolina that brought more than 100,000 people to rallies across the state protesting voting restrictions and corporate-funded extremist legislation, and had sister rallies in several other states. But this wasn’t a spontaneous eruption—the broad-based coalition behind Moral Mondays first formed in 2007 to advocate for expanding voting rights.

In this book Barber, a Disciples of Christ pastor and president of the North Carolina chapter of the NAACP, uses autobiography and U.S. history to root the story—the successes, failures, and wisdom gained—of the work that led to the Moral Mondays campaign and beyond.

As a young pastor, Barber learned valuable lessons when he participated in a failed effort to unionize a textile factory in Martinsville, Va. In the aftermath, he meditated on Psalm 94 (“Who rises up for me against the wicked? Who stands up for me against evildoers?”) and found there the spiritual mandate for sustained moral dissent, even when political victory is out of sight. But he also took an honest look at his strategic failings; a key one was not bringing white pastors and workers into the effort, allowing the white factory owners to divide and conquer the workers along racial lines. His wariness from his own negative experiences with white people had tripped him up. He writes:

Sacred Courts

Andrey Bayda / Shutterstock

IN 2000, sophomore Onaje X.O. Woodbine was Yale basketball’s leading scorer and one of the top 10 players in the Ivy League. From the outside it must have seemed like a dream come true for a young man who grew up playing street ball in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston.

But Woodbine felt isolated and excluded by the white players on the team, troubled by what he’s described as “a locker-room culture that encouraged misogyny,” and hungry to focus on his studies and wrestle with deeper philosophical and theological questions. So he quit basketball.

Woodbine eventually returned to the courts of his youth as a researcher, studying the practice and culture of street basketball for his doctoral studies in religion at Boston University. Woodbine is the author of Black Gods of the Asphalt: Religion, Hip-Hop, and Street Basketball (Columbia University Press) and a teacher of philosophy and religious studies at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass. He spoke with Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter in May.

Julie Polter: What led you to study street basketball from a religion scholarship angle?

Onaje X.O. Woodbine: When I was 12 years old, I lost my coach. He was my father figure; I didn’t have my father for most of my early childhood. It was just devastating.

I went to the court the next day to look for him. I felt his presence in that space. It was really the only place, looking back, where I felt safe, I felt whole, where I felt like my inner life was valuable, where there was a whole community whose interest was in my growth as a human being.

From the Archives: July-August 1995

NATALIA61 / Shutterstock

CAN THE words “Christian” or “faith” appear in proximity to political issues? And if they do, what should they mean? On May 23, a delegation of U.S. Christian leaders came to Washington, D.C., to proclaim to the press and the country’s political leadership that yes, faith and values are vital to the public life—and if they are genuinely expressed they should transform our discourse, policy, and social fabric. What true biblical faith doesn’t do is let religious conviction be manipulated by partisan politics.

“America is fed up with what many in the church are doing, polarizing us into Left and Right. Christians are called to a politics of reconciliation,” said Tony Campolo at a press conference held that morning. ...

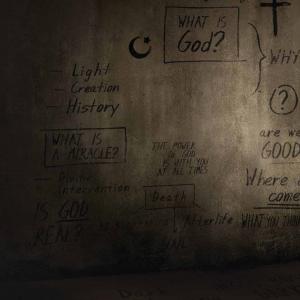

Godly Stories

FEELING STRESSED BY CURRENT EVENTS, weary of ugly public discourse and the contentious sniping among even those who claim the same political party or faith? Maybe what you need is context—a look at the sweep of history and the enduring mysteries of existence. It’d be nice if there were a guide. Perhaps someone with a rich, velvety voice and calm presence to accompany you to far-off places and times—even better, to take you there on a private jet—and to not only ask deep questions but arrange for experts to posit answers.

You may be in luck: The Story of God is a six-part documentary series scheduled to air weekly on the National Geographic cable channel beginning on April 3. Actor, producer, and Story host Morgan Freeman travels the globe to glimpse how some religions (and a bit of modern neuroscience) attempt to answer our big human questions. Is there life after death? How was the universe created? Will the world end, and how? Who is God? What is the root of evil and how has our idea of it changed over time? Are miracles real?

(Let’s just get this out of the way now: Yes, Freeman has played God in two feature films, Bruce Almighty and its sequel Evan Almighty. No, he is not reprising the role in The Story of God.)

Given the enormity of the task Freeman and the other producers set for themselves—wrestling with theological conundrums, including some perspective from ancient beliefs and each of the five major world religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism), shooting in 13 countries, and whittling all that footage down to six hours total for airing—they did admirable work. It’s impossible to go deep or broad into a religion within those kinds of constraints, but the threads of history and theology presented, and the experts presenting them, are interesting and legitimate. There are bits of melodrama in the framing of Freeman’s quest and in some of the dramatizations of historic events, but this is edutainment TV, not a graduate school seminar.

Sermons for Life

PREACHING A SERMON on an issue debated in the public square: It’s complicated. Make that issue the climate crisis, and it’s really, really complicated. Even in congregations where climate change is not broadly disputed, a pastor faces the challenge of crafting a gospel-informed message that doesn’t swing either to naïve ways we might “make it all better” or pessimistic apathy.

But there’s evidence it’s worth the work and risks: In terms of policy issues, climate is one where a clergy leader’s word has proven impact. According to a 2014 survey by the Public Religion Research Institute and the American Academy of Religion, Americans with a clergy leader who “speaks at least occasionally about climate change” are more likely to be concerned about the issue than those “who attend congregations where the issue is rarely or never raised.”

So where does a preacher begin and with what goals?

Leah D. Schade’s Creation-Crisis Preaching equips pastors to name the present crisis and preach a call to action and healing. She describes one theological path to sermons infused with both testimony of the sacredness of God’s creation and our call to be agents of the world’s healing. Schade is a Lutheran pastor and anti-fracking activist who has also done doctoral work focused on homiletics and ecological theology. Appropriately, in this book she explores both the theoretical underpinnings and the practicalities of climate-crisis preaching. Her approach is clear-eyed about the current dire situation of creation, but also committed to hope: “Because I am a Lutheran homiletician,” she writes, “I am compelled to find a way to preach the eco-resurrection, even when most signs indicate that Good Friday may be the fate of our planet.”

Schade sketches the sometimes contentious and damaging history of religion’s relationship to the environment, some different approaches to ecological theology, and a “‘green’ hermeneutic for interpreting scripture.” She explores briefly how social change theory can inform the vocation of preaching and the role sermons might play in a social movement.

'Spotlight' and the Value of Truth-telling

Early in the film Spotlight, about the Boston Globe investigative reporting team that exposed the decades-long cover-up of sex abuse by Catholic church leaders, a Globe reporter is shown at Mass with her grandmother. The priest, launching his homily, says, “Knowledge is one thing. Faith is another.”

In a simplistic film, this binary statement might set the tone for a black-and-white portrait of journalists as pure heroes and people of faith as solely hypocrites and worse. But Spotlight works with characters not caricatures; not one-dimensional heroes and villains, but real people who sometimes choose expediency and sometimes courage. No one is shown to be flawless, not even the reporters and editors who do great good in bringing to light systemic crimes.

But the movie does illustrate quite clearly one tension between knowledge and faith: The guardians of institutions, including churches, can fear knowledge to the point of pathology.

Inspiring Pages

focal point / Shutterstock

BY NOW you’ve probably heard of a little book of hard analysis and eloquent perspective that came out this summer, Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau) by Ta-Nehisi Coates. (If not, get thee to a book store or library.) Here are some other books—some out this fall, others from earlier in 2015—that you’ll want to know about.

Fresh This Fall

With Understanding Mass Incarceration: A People’s Guide to the Key Civil Rights Struggle of Our Time (The New Press), James Kilgore has written an accessible field guide to an urgent topic. Geraldine Brooks gives King David the novel treatment in The Secret Chord (Viking). Aviya Kushner plumbs translation inThe Grammar of God: A Journey into the Words and Worlds of the Bible (Spiegel & Grau). Kathryn J. Edin and H. Luke Shaefer profile families enduring poverty in $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Inventing American Religion: Polls, Surveys, and the Tenuous Quest for a Nation’s Faith (Oxford) is Robert Wuthnow’s case for why sometimes data is dubious.

In the children’s picture book Mama’s Nightingale: A Story of Immigration and Separation (Dial), Edwidge Danticat tells the stories of many through one little girl. Sarah Bessey tells us to be not afraid of questions inOut of Sorts: Making Peace with an Evolving Faith (Howard Books). Women write their truth inFaithfully Feminist: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Feminists on Why We Stay (part of the I Speak for Myself series), edited by Gina Messina-Dysert, Jennifer Zobair, and Amy Levin.

The Hide-and-Seek of Faith

CANADIAN ARTIST William Kurelek was influenced both by his experiences with mental illness and his conversion to Catholicism. He would eventually be considered psychiatrically recovered, but he was institutionalized as a young man in the mid-’50s, during which he created one of his best known early paintings, showing a blind man wandering in a desert, captioned “Where am I? Who am I? Why am I?”

These are foundational questions for all of us, not just a gifted artist in a time of suffering. The institutional church tends to assert that the answers to such questions are, if not simple, at least imminently knowable: Just pull up a pew and stay awhile. Many of us who are already believers come to assume that our job is to have a spiritual GPS always on, ready to point others in the “right” direction.

But of course, finding God or our place in the universe has rarely been that easy. Church may or may not be the place where we who are lost are found. The person we’ve always claimed to be may be shattered by unexpected events or discoveries. Or theologies that we once took for granted may come to ring hollow. As Diana Butler Bass writes in her new book, Grounded: Finding God in the World, “millions of people are navigating the space between the secular world and conventional theism. They are making a path between the two that nevertheless embraces both, finding a God who is a ‘gracious mystery, ever greater, ever nearer’ through a new awareness of the earth and in the lives of their neighbors.”

Several other very distinct books released this year wrestle with the shape of faith, finding or naming God, and how secrets revealed can shift our self-understanding and shake even our deepest beliefs.

In her best-selling 2013 spiritual memoir, Pastrix: The Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner & Saint, Nadia Bolz-Weber described her journey from fundamentalist childhood to alcoholic rebel to believer with a priestly call. A tattooed, weight-lifting former standup comedian who is now a Lutheran (ELCA) pastor, Bolz-Weber helped found House for All Sinners and Saints in Denver, which combines ancient liturgy and theological orthodoxy with artistic expression, social justice, and radical inclusion.

‘That Song You Sing For The Dead’

BIBLICAL LAMENT includes both pleas to God for help and mournful dirges. Sometimes they are rooted in individual travails and grief, other times in anguish for those crushed by injustice or war.

The psalmist and the prophets dig deep into visceral images of bodily suffering—and stretch up, out, yearning to find symbols and metaphors in nature that might capture the mercy and presence of a God who, the psalmist isn’t afraid to say, is sometimes a bit elusive.

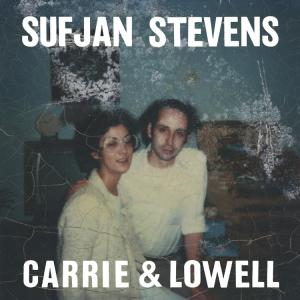

Songs of Ourselves: Grief, Hope, and Sufjan Stevens

Sufjan Stevens’ newest album, Carrie & Lowell (out now), is a heartbreaking meditation on personal grief. It’s also joyful, baffling, and delicately mundane.

In the spirit of a listening party, a few of us sat down to play through the album, sharing liner notes and meditations on the songs that grabbed each of us. Conclusion: it's really, really good. Stream Carrie & Lowell here, and listen along with us below.

“Death With Dignity” — Tripp Hudgins, ethnomusicologist, Sojourners contributor, blogger at Anglobaptist

Tripp: I love the first song of an album. I think of it as the introduction to a possible new friend. “Where The Streets Have No Name” on U2’s Joshua Tree or “Signs of Life” on Pink Floyd’s Momentary Lapse of Reason, that first track can be the thesis statement to a sonic essay.

So, when I get a new album — even in this day of digital albums or collections of singles — a first track can make or break an album for me. I sat down and listened attentively to “Death With Dignity.” It does not disappoint. With it Stevens introduces the subject of the album — his grief around troubled relationship with his mother and her death — as well as the sonic palate he will use throughout the album.

Simple guitar work, layered voicing, and a little synth, the album is musically sparse. The tempo reminds me of movies from the nineteen sixties or seventies where the action takes place over a long road trip.

Catherine Woodiwiss: I was thinking road trip, too. There’s real motion musically, which, given a claustrophobic theme and circular lyrics, is a thankful point of release. It’s a generous act, or maybe an avoidant one — he could have made us sit tight and watch, and he doesn’t quite do it.

Julie Polter: This isn’t a road movie, but the reference to that era of films just made me think of Cat Stevens’ soundtrack for Harold and Maude, especially “Trouble.” (This album is one-by-one bringing back to me other gentle songs of death and duress and all the songs I listen to when I want to cry).

Were You There?

THE GRAINY, STUTTERING surveillance footage shows police milling about, offering no medical assistance to the 12-year-old boy, Tamir Rice, one of them has just shot. They only spring into action when the boy’s older sister runs into the frame toward her brother. An officer tackles the girl, knocking her back in the snow, then cuffs her and puts her in the patrol car, only a few feet from her dead or dying brother.

This extended footage, released in January, and bystander cell phone footage from a few minutes later with audio of the sister wailing over and over “they killed my brother,” brought into my head the Good Friday spiritual “Were You There?” It was another moment, in months of unrest over police killings of black adults and children, when the question pressed in on me as a white person. “Were you there? Were you there when they choked my father dead? Were you there when they shot my son? Were you there when they killed my brother? Were you there?”

While books and other cultural works are no substitute or shortcut to the spiritual work of true repentance and detoxifying from cheap grace, they can be means of deepening understanding and finding the resolve to take action. Along with the film Selma, following are some of the artistic resources I’m turning to this Lent.

Noel Paul Stookey and Peter Yarrow: 50 Years of Song in 'Love of Community'

The folk trio Peter, Paul, and Mary had almost 50 years together until Mary Travers’ death in 2009. Peter Yarrow and Noel Paul Stookey continue as musicians and activists, and have reflected on their experiences in a new a photo-filled book Peter, Paul and Mary: 50 Years in Life and Song (Imagine/Charlesbridge). A just-released album, DISCOVERED: Live in Concert, includes 12 live songs never before heard on their albums. And on Dec. 1 (check local listings), PBS will air 50 Years with Peter, Paul and Mary — a new documentary with rare and previously unseen television footage and many of the trio’s best performances and most popular songs.

I spoke with Yarrow and Stookey this week about music, movements, and the spiritual aspects of both. (Stookey had what he describes as a “deep reborn experience” as a Christian around 1969 or 1970; Yarrow doesn’t affiliate with a specific religious institution, but describes much of what motivates him in spiritual terms.)

Stookey describes how all three of them were drawn to carrying on the precedent of folk forebears such as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to make music “in the interest of, and love of, community.” Their appearance at the 1963 March on Washington was, he says, “the galvanizing moment” for their activism, the beginning of a trajectory that would engage them in the civil rights, peace, anti-nuclear, environment, and immigration movements, and “less media-covered causes and events — a rainbow of concerns that we were inevitably and naturally drawn into.”