Lisa Sharon Harper, a former Sojourners columnist, is the founder and president of Freedom Road and author of Fortune and The Very Good Gospel. You can follow her work at lisasharonharper.com.

Posts By This Author

Find the Cost of Freedom

Everett Historical / Shutterstock.com

THEY CAME TO the front and waited to speak with me. They were weeping.

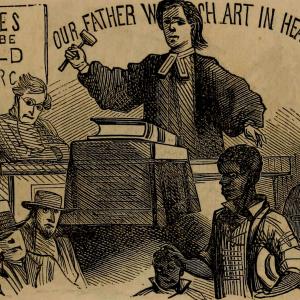

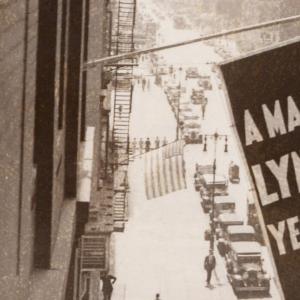

The day before, I sat in the front seat of a packed car. Five beautiful black women, including one of the women now in tears, rolled toward Marion, Ind.—the site of the last public lynching in the North.

On the sweltering summer night of Aug. 7, 1930, three African-American teenagers—Thomas Shipp, Abram Smith, and James Cameron—sat huddled in their jail cells in Marion. Thousands of white men, women, and children gathered outside the jailhouse, screaming and jeering—demanding blood. The three were charged with the ultimate sin against whiteness—killing a white man and raping a white woman. They were dragged from the jailhouse, beaten, and strung up on a low-hanging tree branch a block away on the courthouse square, in the center of town. For some reason, Cameron was spared. The other two were not.

The town photographer captured the moment: The mob congregated like lions around mangled prey. Lips licked, satisfied grins splayed across the faces of young women and old women, young men and old men. Floral dresses, white shirts with buckled pants, and hats atop straight-backed heads covered bursting egos as they reveled in victory. One man pointed to their ritual sacrifice, and that moment became an iconic illustration of American lynching.

Shop 'til They Drop

woaiss / Shutterstock

TWO WEEKS BEFORE Christmas last year, I stood with 50 other national faith leaders on the banks of the Alabama River in Montgomery, Ala., trying to imagine what it must have been like to stand on that land in 1850, at the height of the black chattel slave trade.

We were embarking on a one-day pilgrimage convened by Sojourners and hosted by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). We were there to understand one thing: the nature of the confinement and control of black bodies in the U.S. from chattel slavery through Jim Crow to mass incarceration.

Congress banned the import of enslaved people in 1808, but it did not ban the slave industry. Slave traders turned inward. Men, women, and children of African descent were sold in the Upper South; chained together with shackles around their feet, wrists, waists, and necks; and marched—often without shoes—over hundreds of miles into the Deep South for sale to farm owners desperate to meet the explosive global demand for cotton after the invention of the cotton gin.

“But walking was too slow and expensive to meet the high demand,” said Bryan Stevenson, founding executive director of EJI, to the faith leaders standing at the mouth of Montgomery’s Commerce Street. Stevenson explained that sales multiplied as transport methods improved. By the 1840s, the Commerce Street port housed a steamboat dock and a train station. Rather than marching 20 people over hundreds of miles, traders could transport hundreds of en-slaved people at a time—quicker and less expensive. Slavery was industry. Even in these early iterations, maximizing profit and lowering the bottom line were of chief concern.

According to a 2013 EJI report, “Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade,” Montgomery’s Commerce Street became one of the most easily accessible points of trade in Alabama by 1860. Slave traders would unload humans from ships and trains at the top of Commerce Street and auction them three blocks away at Court Square. Auctioneers coaxed farm owners to push bids higher until the auctioneer cried “Sold!” Mothers were separated from sons and daughters. Sisters were separated from brothers. And husbands were separated from wives. Humans were forced to fill days with bone-breaking labor, heartache, and absolute acquiescence to the domination of overseers and masters—until death freed them from the clutch of American commerce.

Rights Worth Defending

THIS SPRING I sat with former President Jimmy Carter and 150 others to talk about human rights.

Women and men from Pakistan, Iran, Israel, Palestine, DR Congo, Indonesia, South Africa, Mexico, Colombia, Nigeria, Syria, Iraq, Russia, Ukraine, the U.S., and other nations attended the Carter Center’s #FreedomfromFear Human Rights Defenders Forum in Atlanta in the midst of a year marked by increased attacks on human rights and on the people who defend them.

Yuri Dzhibladze, president of the Moscow-based Center for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights, shared what he had learned about authoritarian leaders by defending human rights in Putin’s Russia. “For authoritarian leaders to take power,” Dzhibladze said, “they must propagate the belief that they are the protectors of their countries. They must cast multiple actors as imminent threats.”

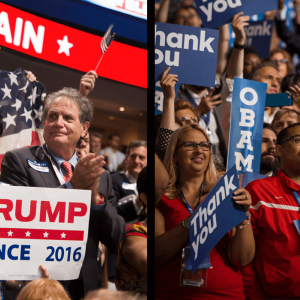

Donald Trump’s campaign declaration rang in my ears: “I alone can fix it,” Trump said at the GOP national convention. Inside the Beltway those words sounded insane, but, according to Dzhibladze, Trump was simply reading from the authoritarian leaders’ handbook 101. “In authoritarian regimes,” Dzhibladze said, “propaganda dehumanizes scapegoats. Meanwhile, devious enemies are always plotting against us.”

Trump vs. Jesus

I HAIL FROM a theological tradition that places the highest value on epistemology, the study of how we think about God, yet tends to invest little energy on ethics, the study of how we are called to interact in the world.

Likewise, many in my theological tradition place ultimate value on one’s capacity for faith in particular sets of beliefs—and tend to demonstrate hostility toward historical, anthropological, philosophical, and scientific methods to shape those beliefs, unless those methods happen to support the tradition’s faith-born premises. Think: climate-change denial. This article of faith is partially rooted in profound belief in a particular reading of Genesis 1:26 and human dominion. It is not rooted in science.

Perhaps this reveals one reason why so much of the white evangelical community saw no red flags when Donald Trump refused to show his tax returns. They believed in him. They did not need to see evidence.

Perhaps this is the reason it does not faze many white evangelicals that Trump trafficked in fake news, conspiracy theory, and innuendo to win the presidency and continues the practices in the aftermath. Trump’s relationship to fact may mirror their own. It almost seems as if life in this world and the hard facts that govern life have nothing to do with anything. I’m thinking of the fold-over tracts or Facebook posts that fly through evangelical circles during every presidential election cycle. They claim the Democratic candidate is the Antichrist and warn of the horrors if she or he is elected. It doesn’t matter if the Democrat or the Republican promises to protect the poor. All that matters is which one assures the voter’s stature in the afterlife. And who wants to go to hell because they voted for the Antichrist? Not me.

The Battle Against Black Freedom Wasn't Nonviolent

The rifle used to kill Medgar Evers. Image via Wikimedia Commons

IN JUNE 1964, 54 years ago this month, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael “Mickey” Schwerner were asked by leaders of the Congress of Racial Equality to investigate the burning of a black church that had doubled as a Freedom School in Neshoba County, Miss.

More than 1,000 people, including college students, boarded buses bound for Mississippi that year. Over the preceding four years, these young people had witnessed a Southern sea change, from school desegregation to the integration of lunch counters, buses, bus depots, and movie theaters. They witnessed the Children’s March in Birmingham—hoses, dogs, terror faced down by black children who did not run. They stood their ground and they filled jails and they sang about overcoming. These previously silenced and subjugated people were now using the only thing they had—their bodies—to break through. And they had broken through.

Nashville, Greenville, Mont-gomery, Birmingham ... Now, it was Mississippi’s turn. James Meredith had served as the tip of the spear in 1962 when he registered for courses at Ole Miss. Mississippians lost their minds. The ensuing riot required 31,000 National Guards to quell it and left two dead and hundreds wounded. Meredith did register—and was graduated—but Medgar Evers, field secretary of the NAACP in Mississippi, was assassinated the following year, in his driveway.

It Didn't Start with Trump

A WHITE EVANGELICAL leader recently asked me how white supremacy shaped Republicanism. The truth is this: Belief in the supremacy of whiteness has shaped both parties and all facets of life in the United States.

The Grand Old Party wasn’t always synonymous with bold-faced bigotry. In fact, it wasn’t even synonymous with the South. The party of Lincoln was crafted in the North in 1854 to counter the expansion of Southern slavocracy into new territories.

As the only surviving party from the nation’s founding, Democrats—based in the South—were keepers of the status quo, maintaining the health of the nation’s nascent systems and structures. The two parties morphed into the two sides of the Civil War: the Union (Lincoln’s Republicans) and the Confederacy (Southern Democrats).

Lincoln’s GOP won and spent the first several post-war years reordering the landscape of power in the U.S.: They outlawed the 246-year-old American economic engine known as slavery, removed race as a determining factor of citizenship, and expanded the right to vote to all male citizens, regardless of race. Formerly enslaved Africans in the U.S. flourished. An estimated 2,000 were elected to public offices across the country—as high as lieutenant governor—and several won seats in the U.S. Senate. But their streak ended when federal troops were pulled out of the South.

Over the next couple of decades, Southern Democrats mounted a legal, social, and political civil war to re-establish white male supremacy in the South. Peonage laws filled former plantations with convict-leased workers by lowering bars of criminality and focusing enforcement on communities of color. Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,000 black bodies swung from trees across the South while white mobs rioted, massacring black men, women, and children with impunity in states across the Midwest and Upper Midwest.

Then there was a shift.

Gentrification Isn't the Problem

TO LOOK AT HIM, you know he’s lived a hard life. With ridges creasing his 27-year-old face, my cousin Shack looked me in the eye during a family gathering and helped me understand how hopeless he feels. The people in his Newark, N.J. neighborhood are being pushed out of their community. The Whole Foods and condos that are moving in are raising the costs of rent and food. The neighborhood’s old guard can’t keep up. This is the case in almost every city across the country. In my own neighborhood—Petworth in Washington, D.C.—I have watched condos rise around me and Starbucks and small bistros move in over the last six years. When I moved here in 2011, taxi drivers and community veterans told me that, until recently, they considered Petworth one of the most dangerous and impoverished neighborhoods in D.C. Gutted by the violent uprising in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, the adjacent neighborhood Columbia Heights lay abandoned by city services and industry, and given over to poverty and violence, for more than three decades. When the city decided to develop Columbia Heights, it was only a matter of time before they would do the same to Petworth. “But gentrification is not the problem,” Shack said. “Poverty is the problem.” I heard those words and I wanted to push back. The anti-poverty advocate in me wanted to say, “Get with the program, cuz. Gentrification is the devil.” But Shack had a point, a good one. Obviously, repair and development of the neighborhood isn’t the problem—it’s the displacement of often-poorer people by more affluent people that usually goes with it. These neighborhoods should have been repaired and developed decades ago according to the desires of their homeowners and residents.

How Christians Helped Build the Confederacy

“THIS TIFFANY stained glass window was donated by parishioners in honor of Jefferson Davis,” said our guide, Barbara Holley. Holley is a member of the “history and reconciliation initiative” at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Va. St. Paul’s, located across the street from the Virginia general assembly and around the corner from the Confederate White House, was called “the Cathedral of the Confederacy” for a reason. Fragments of stained glass honor Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Gen. Robert E. Lee. Both men gleaned inspiration, comfort, and resources for their cause here. Their pews are marked with commemorative plaques.

Forget 'Once Upon a Time'

“ONCE UPON A TIME ...” We like that. Four words signal to our colonized brains: “It’s story time!” We’re gonna go on an adventure! We’re gonna meet mice and pumpkins and fairy godmothers and wicked stepmothers and oppressed blonde women wearing baby-blue peasant wear and neat white aprons. And we’re gonna fall in loooooove. Ahhhh ...

July 2003. Rolling across the northern South, I follow a story, from tourist trap to tourist trap along the Cherokee Trail of Tears. “Watch the metanarrative,” says Randy Woodley, our guide on the journey. What do the museums, the plays, the tourist shops want Americans to believe about themselves? “God guided us West.” “It was destiny.” “Those featherheaded people became our friends.” Or: “They were dead before we got here.” Or: “They just left. Sure, they were ‘removed,’ but we had a hoedown for the ones who hid in the hills and stayed.”

3 Things Forgiveness Demands of Us

I had a dream last night that I was reunited with estranged family. Watching them live their lives and being separated from them became unbearable. I sat in my family member’s living room weeping, saying: “I can’t do this anymore.” My not-so-little-anymore niece took me by the hand, in my dream. She walked me to a corner in her room where she laid a prayer cloth on the ground, knelt on her knees facing east, and asked me to offer prayers of forgiveness with her. It stunned me. I woke up.

Forgiveness.

Racism Broke Us. What Stories We Tell Will Decide If We Heal.

In an age when both explicit and implicit biases are becoming legitimate justifications to curse the image of God, it is time for the church in the U.S. to face itself. It is time to repair the broken fabric of our nation. It is time to interrogate the stories we tell our selves about ourselves by immersing ourselves in the stories of the other.

Lies Lead to Violence. Where Can United Go from Here?

Check-in area for Premier Access premium passengers at the United Airlines terminal at the Chicago O'Hare International Airport. EQRoy / Shutterstock.com

Someone lied. It’s more acceptable to say, “You’ve been bumped because the flight is overbooked,” than to say, “You’ve been bumped because we want your seat to fly our staff. That lie led to violence. Violence led to trauma for passengers, for millions of viewers, and for United, which sustained a $1.4 billion dive in stock value by Tuesday morning and now seems rested at a $255 million loss.

The Stories of Us

Here’s how: We have been living according to different stories of America’s past. As a result, we interpret the present differently. In turn, we dream a different future.

The Lie at the Root of Injustice

On the Friday morning before Martin Luther King Day this year I met nine twentysomething Sojourners interns at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the National Mall. We collected into a circle, and I told them: “This is sacred ground.” I explained that we would enter the grounds in silence. I instructed the mostly white group to spend 15 minutes examining the memorial — observe — see what they see. Then we would come back together and share what we saw.

One Breath at a Time: 16 Hours in a D.C. Jail

One week ago, I emerged from 31 hours in police custody — 16 hours underground in D.C.’s central jail. It was horrific and holy ground.

I was taken underground by officers and placed in a small steel cage — literally, a cage – where roaches flowed into our walls and floor throughout the night. Curled in a fetal position, I tried to sleep on a 6’ x 2’ steel tray.

“Just one breath at a time,” I thought. “You’ll make it,” I told myself. “One breath at a time.”

Keep Watch

I sat on the first wooden pew of the Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C., on New Year’s Eve, with 500 faithful from across the country and thousands who watched online, to worship, testify, and encourage each other.

We came together in the tradition of the 1862 “watch night” service, when enslaved and free African-Americans, abolitionists, and others awaited news that the Emancipation Proclamation would become law and would free black people living in the South. We came together also in the tradition of Jesus, who told his disciples to “keep awake” while he prayed on the night before his crucifixion.

Revelation of Light

On election night, I hunkered down in my living room, eyes glued to the television, waiting for the announcement. When talking heads announced that Hillary Clinton conceded the election to Donald Trump, my body shook — literally. I could not control it. I had never experienced anything like it. A cry rose from the pit of my stomach and quickly turned into a primal scream.

The Roots of InterVarsity's Line in the Sand on LGBTQ Inclusion

Cultural uncertainty was the context in 2011, when Michael was first reported to his staff worker. Uncertainty of campus access and campus culture was the context when managers gathered to forge strategy for the next three years. And uncertainty of InterVarsity staff members’ own convictions and ability to answer students’ questions regarding their sexuality was the context when the Cabinet undertook the task of clarifying InterVarsity’s theological position on human sexuality.

How to Heal Our Ill Nation...and the World

Image via nito/Shutterstock.com

Our nation and the post-colonial world is facing a critical moment. We must face the diagnosis rising from the colonized. We must accept the reality that we are ill. We have been living according to false narratives and led by spiritual lies. And those lies have shaped and ordered life among us since our founding days.

What I Learned About Love at the GOP Convention

What shall we prophesy?

That restoration and repair are possible because God is — because God is love — because love intervenes.