Liuan Huska is a freelance journalist and the author of Hurting Yet Whole: Reconciling Body and Spirit in Chronic Pain and Illness. She lives on ancestral Potawatomi land near Chicago.

Posts By This Author

Christians Must Avoid ‘Lifeboat Mentality’ in Climate Crisis

The latest IPCC report states that 3.3 to 3.6 billion people (nearly half of the world’s population) are “highly vulnerable” to climate risks like wildfires, heat waves, and rising sea levels. The report aims to prepare us for what’s likely and to give leaders a clear-eyed sense of urgency to implement solutions. But some may glance past its findings due to more immediate concerns. Others may be tempted to take a lifeboat mentality.

Can We Only Take Ownership of History That Our Blood Ancestors Experienced?

A FEW MONTHS into the pandemic, as the country started to notice the uptick in hate crimes against Asian Americans, caring friends checked in to ask, “Are you okay?” I found myself metaphorically turning around to see if they were talking to someone behind me. I was so unused to having my ethnic vulnerability seen and named.

Then a year ago, in March 2021, a young white man killed six Asian women in spas around Atlanta. This time it was clearer—I was not okay. My mother is a massage therapist and has worked in spas in Florida, where the killer was headed when police apprehended him. This time, I could say with more certainty, “This hurts me.”

In the blooming of Asian American consciousness since that event, however, I’ve continued to wonder how much of what happens to other AAPI (Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders) folks around the country, and back through time, is mine to own. Writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that Asian Americans who came to this country after the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration Act have little to no connection with earlier generations of Asian Americans, whose circumstances were vastly different. Between the lines, Kang is saying to us later waves of immigrants, “That’s not your history.”

The Discipline of Delight

IN JULY, my children and I crouched at the edge of the continent along a trail spitting hikers onto Kalaloch Beach 1 in Olympic National Park. Eyes at dirt level, we marveled at a hidden-in-sight banana slug, oozing exquisite slime and swiveling its tentacles. Off Interstate 90 in Montana, we held our breath as a bald eagle swooped over a deer grazing just across the fence from our car. Throughout our epic road trip from Illinois to the Pacific Northwest, I kept saying, “Wow, but ...”

My wonder was tinged with a sense of impending loss. With fires devouring unthinkable amounts of forest just over the next mountain range and smoke clouding the skies for 1,500 miles, the beauty in front of me seemed to be slipping away. In the end, I took home more pain than joy.

Many of us live with this bone-deep grief over what we have lost in the natural world, and with anticipatory grief over what is about to be lost. It is right to feel this deeply, to lament and give voice to our pain in community. And then what? Grief, pain, and anger can move us to action, but they only carry us so far. To sustain our work, we need joy.

Returning to the Path of Sacred Attachment

“THIS WORLD IS not my home / I’m just passing through / My treasures are laid up / Somewhere beyond the blue.” This old gospel song summed up my approach to the physical world as a young Christian.

Coming to faith in the Bible Belt of the United States, I confused admonitions to “not belong to the world” (John 15:19) and “walk not according to the flesh” (Romans 8:4) with a blanket statement to shun physicality. Later, when I discovered the contem-platives and monastics, their stories of fasting and asceticism seemed to reinforce the idea that detachment from the material world is the most holy path.

But in a time when some Bible-thumping Christians respond to deforestation and species extinction with a shrug and say, “It’s all going to burn anyway,” I reject these interpretations. “The world” and “the flesh” that Jesus and Paul had in mind are not the earth and our bodies. They are, rather, human-made social hierarchies and oppressive, extractive economies. Do not belong to these. But do belong to the gooseberries, the crickets, the soil, and the gurgling creeks.

Toward More Productive Climate Conversations

AMONG THE MANY postures toward climate change, I am in the “alarmed” camp. I see indicators of a planet on the verge of widespread ecosystem collapse and want to sound the bells for everyone else to wake up and do something. Unfortunately, writes climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, some of the ways we try to wake people up can have the opposite effect.

Saving Us expands on Hayhoe’s popular TED Talk on the most important thing you can do about climate change: talk about it. The book explores why piling on sobering facts and predictions can make someone dismissive about climate change even more antagonistic, and even make those who are concerned and alarmed check out in despair. Though Hayhoe includes plenty of climate science, what makes this book worth reading are the insights she shares from social science.

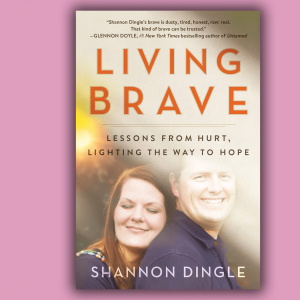

Finding a Way Back to God After Tragedy

Shannon Dingle is a disabled activist, sex trafficking survivor, and author of recently released Living Brave. Her family’s grief over the sudden death of her husband, Lee, in July 2019 resonated with many worldwide. She discussed Living Brave with Liuan Huska, author of Hurting Yet Whole: Reconciling Body and Spirit in Chronic Pain and Illness.

LIUAN HUSKA: IT’S been almost two years since a rogue wave killed your husband, Lee, on a family beach vacation. You wrote about his death soon after it happened.

Shannon Dingle: Looking back on some of my writing, I’m so damn proud of my ability to capture where I was then. It is a record for me and my kids as much as for anyone else. I wanted to tell the story and protect how it was told.

Did the sexual abuse you experienced as a child influence how you wanted to tell your grief story? My brutal and raw honesty definitely comes from a place where I had horrific things happening that I couldn’t tell. I know how freeing it can be to put words to things. I write from a place where I know I’m the authority on what my life has been and what happened.

Mary and Other Displaced Brown Mothers

Like Mary, women the world over have had their childbirth plans disrupted by the pandemic, their path to motherhood rerouted, especially women of color.

Fueled By Faith, Not Fear

THE LAST THING that Ben Lowe could be accused of is “slacktivism,” which, as he describes in his latest book, Doing Good Without Giving Up, happens when we complain and point fingers about justice issues while being slow to take constructive action to address the situation.

From running for Congress at age 25 to helping to ignite a grassroots student environmental movement, Lowe’s track record for tackling complex and thorny problems where others would throw up their hands is remarkable. Even more remarkable is that after nearly a decade of such work, Lowe retains a gracious hope and steadfast sense of calling, despite being told by other Christians that he was being deceived by the devil, weathering bouts of burnout and depression, and continually facing entrenched systemic problems. This is why I trust him when he writes to encourage those of us whose hearts are heavy for the injustices in the world but often find ourselves stuck in the initial “slacktivist” inertia or dragged down later by opposition, burnout, and cynicism.

In Doing Good, Lowe outlines a sustainable impetus for social action and offers practices to sustain ongoing activism. We cannot be motivated by the desire to see dramatic change, he says, because this only “points people to ourselves and idolizes the change we seek.” It also ultimately lacks staying power. Instead, Lowe calls us to pursue faithfulness in our social action, which “points people to Christ ... and is ultimately the best—if not only—way to bring about the change God seeks.” Staying faithful, which the second half of the book covers, requires a continual reorientation to Christ as center through such practices as repentance, Sabbath, contemplation, and community.

Prophet in a Cracker Dress

ONE RECENT WINTER day, Nora Howell stepped out of her house in the Sandtown neighborhood of Baltimore and took a walk down the street. People in the predominantly black community did double takes as this white woman promenaded past them in a sundress made of saltine and oyster crackers. Some stared in disbelief. One man doubled over laughing. In the corner coffee shop, one of the regulars warned Howell not to walk by any homeless people because they might just eat her up.

Later Howell, a community artist and director of the neighborhood Jubilee Arts program, set the video footage taken during her walk to Mister Rogers’ classic refrain, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” The piece, which emerged out of Howell’s ponderings on what it means to be white living in a black neighborhood, became another part of her answer to a call: to use art to address systemic racism and bring about the kingdom of God.

From Race Riots to White Suburbia and Beyond

In 2001, Howell was an eighth grader living in a biracial community in urban Cincinnati. When race riots erupted after a young black man was shot fatally by a white police officer (sound familiar?), her family took to the streets on a prayer walk through the riots. Howell remembers being shocked and terrified, thinking, “Why do we still have race riots? Cincinnati is so far behind the times.”

In the aftermath, Howell talked with peers at school on the reality of racial tensions and observed with curiosity how white and black churches throughout the city responded. She realized race riots weren’t just a relic of the ’60s. “When you lived in a place where different racial groups interacted daily, [racial tensions] could no longer be denied or ignored,” she said.

Yet when Howell moved to suburban Chicago to attend Wheaton College, conversations on race were largely absent. “I found that very odd,” she said. She got involved in a campus group to promote awareness of racial injustice.