Faith communities across the country are drawing from deep wells of legacy to organize and advocate for a more just world. People of faith are returning to their spiritual roots for guidance on how to engage the world’s struggles for justice in ways that honor our faith. To equip faith communities to boldly do the work of justice in their own areas, Sojourners offers the Faith in Action series. Learn more about how to put your faith into action here.

Refugees pass from DR Congo into Uganda in 2008, Sam DCruz / Shutterstock.com

I can still see in my mind’s eye the vibrantly colored wraps draping the hundreds of displaced women I met at Joborona Camp in Northern Sudan. The stories they told, of blazing huts in Southern Sudan and their men burning alive inside; of their boys forced to fight and kill at ages as young as six or seven; and of their girls taken and forced into sexual slavery seemed impossible to be true. Yet I heard them again and again.

And if these stories weren’t horrific enough, it was the stories the women chose not to share that haunt me the most. Their empty eyes and void expressions told me all I needed to know.

I know empty eyes. I have gazed into them in Bosnia and Croatia. I remember Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. I have witnessed them in the Democratic Republic of the Congo — where it is believed that one million girls and women have stories to tell of the gender-based violence they have endured. I have been confronted by the eyes of our sisters from Darfur, who risk their dignity, their bodies, and in some cases their very lives by leaving their refugee camps to collect firewood for their small cooking stoves (those who are lucky enough to have one). It is in the bush, often, that they are victims of sexual and gender-based violence. These are the countless women who risk being raped so their children can eat.

Sex trafficking illustration, ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock.com

Eight years ago I left my dorm room, humming the hook to “Till I Collapse” on my walk to the bathroom. When I returned a new song was playing on my laptop. Ludacris’ “P-Poppin’” pierced through the thin walls and echoed down the hallway. I bobbed my head along and then sat down to finish my homework. I looked at the screen, and I thought I saw my sister.

One of the women on the screen in the strip club swinging around a pole trying to seduce Ludacris looked like Jennifer – my older sister.

And something began to shift.

Stained glass window depicting Adam & Eve, jorisvo / Shutterstock.com

Two things are clear in both creation stories: 1) both men and women are created to exercise equal dominion, and 2) according to Genesis 1:31, this relationship between men and women was “very good.” This is what right relationship between men and women looks like. It is only after the fall of humanity — when we decided not to trust God’s ways, when we decided to grab at our own way to peace and gratification — that women were subjected to men. And I see nothing in the text that says this is the way God wanted it. Rather, I see this is the natural result of choosing to exercise a human kind of dominion rather than one that reflects the image of God. Humanity grabs at its own peace at the expense of the peace of all.

Hand holdng a mustard seed, ptnphoto / Shutterstock.com

This year marks the 150th anniversary of both the issuing of Emancipation Proclamation and the battle of Gettysburg. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the historic March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. All three moments marked major turning points in the fundamental American struggle to actualize the divine dream of life, liberty, and equality for all. That dream has been especially powerful through the struggle for African-American freedom.

From a biblical perspective, American slavery and Jim Crow segregation not only subjugated the body. For about 300 years, from Virginia’s first race-based slave laws in the 1660s to the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the legal binding of black hands, feet, and mouths also bound spirits and souls. Both slavery and Jim Crow laws denied the dignity of human beings made in the image of God and forbade them from obeying God’s command to exercise Genesis 1:28 “dominion” — in today’s terms, human agency.

So, the Emancipation Proclamation and passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were cause for jubilee worship in black churches and among other abolitionists. Likewise when the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965, churches across the nation erupted again in worshipful jubilee.

Now, nearly 50 years after the second American jubilee, African Americans are being stripped of dignity and constitutionally protected freedoms like we have not seen since Jim Crow.

Protestors in San Diego react to the George Zimmerman verdict on July 20, betto rodrigues / Shutterstock.com

Several years ago, Michael Emerson and Christian Smith criticized the quick-fix approach to racism found in the evangelical race reconciliation movement. They noted that evangelicals tended to address systemic racism through promoting interracial interactions at one-time events such as Promise Keepers rallies. Ironically, this approach tended to increase rather than decrease racism because it gave white evangelicals just enough exposure to people of color to think they now understood race without enough systemic interaction to expose them to the endemic nature of racism. They suggested instead that the preferred response was to engage in political and legal advocacy in order to change the institutional nature of racism. However, what they failed to address in that book is that political and legal approaches to race often suffer from the same quick-fix approach.

Today, we see the same quick-fix dynamics in the outcome of the George Zimmerman trial. Some are focusing again on developing interracial interpersonal relationships, while other evangelical groups have focused on legal advocacy. But in our rush to promote a “solution,” we may end up creating more harm than good. I believe evangelicals have the possibility of addressing racial injustice in a more creative way that could get more closely to the roots of the problem if we took the time to think creatively.

Martin Luther King, Jr., quote at the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Ala. Danny E Hooks / Shutterstock.com

I was born in 1969 and thus am in the first generation of African-Americans to grow up with laws and policies that say to the rest of America that I am equal. I saw housing opportunities open up for me as my parents “broke the block” and became the first African-Americans to move onto an all-white block in the East Mt. Airy section of Philadelphia in 1970. I saw educational opportunities open up such that I was able to attend a nearly all-white private, college-prep high school in the suburbs. This was the fruit of the Civil Rights movement in my life growing up in the 1970s and 80s.

Soon hundreds of thousands will gather on the National Mall to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. That speech lived on for me in classrooms and in speech competitions and was etched on my heart so that I would carry that dream into the future.

The recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court to gut the enforcement section of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the decision of the jury in the George Zimmerman trial have left me wondering about the dream, worried that it is under attack and worries that professed Christians are among those helping lead those attacks.

Where do we go from here?

From the denial of racism to the naming and facing of racism.

If we are to move forward, we must acknowledge that racism is alive and well in the American psyche. It continues to function as a demonic force with devastating consequences for us all. To be white in America is to benefit from a system of power and privilege whether or not one has ever uttered a racist thought or committed a racist act.

Neighborhood watch sign on a gate. Photo courtesy gabriel12/shutterstock.com

Florida’s “stand your ground” law — a source of collective ire at present — is an iteration of the Good Samaritan Laws that exist in this country: laws that offer protection from lawsuits for those who help or protect their neighbors. If you dig a hole to save a child’s life, that child’s family can’t sue you for damage to their lawn. Sounds like a good thing, right? Sounds like the spirit of these laws comes directly from the Bible.

Neighborhood Watch programs are born from the same spirit: they empower those who want to protect their neighbor with the authority to do so. George Zimmerman was allowed to have a gun so that he could be a Good Samaritan.

The problem with Neighborhood Watch programs and stand your ground laws is that, in their rush to be the Samaritan in the story, they never ask the question the lawyer asks in Luke 10: “Who is my neighbor?”

Chemical slick. Photo courtesy Adam Mooz/flickr.com

Columbia, Mississippi is a small rural town most known as the home of Walter Payton, NFL player for the Chicago Bears. It is also my home — the place where I was born and raised.

On January 1, 1992, Jesus People Against Pollution was founded in Columbia. Residents had discovered that the town had been heavily polluted from the Newsom Brothers/Old Reichhold Chemical Company facility, now closed but still registering high levels of hazardous waste — what the EPA calls a “Superfund site.”

In March 1977, the plant exploded and wrecked the facility and surrounding community. The Old Reichhold Chemical Company abandoned their facility and hired an inexperienced contractor to dispose of the remaining toxins left on the site.

Oil spill illustration, fish1715 / Shutterstock.com

In his letter to the Romans, the apostle Paul writes: “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God …” (Romans 8:18-19)

And who are God’s children in the immediate context? Paul explains the “children of God” are those whose spirits cry “father” when referring to God. “For,” according to Paul, “all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God.” (Romans 8:14) If this is true, then why is creation longing for the children of God (those led by God’s Spirit) to be revealed?

In Genesis 1, the author writes, “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good.” The Hebrew words for “very good” are mehode tobe. Mehode means “forcefully” and in the Hebrew context tobedoes not necessarily refer to the object itself. Rather it refers to the ties between things. So, when God looked around at the end of the sixth day and said, “This is very good,” God was saying the relationships between all parts of creation were “forcefully good.” The relationship between humanity and God, men and women, within families, between us and the systems that govern us, and the relationship between humanity and the rest of creation — the land, the sea, and sky and all the animals and vegetation God created to dwell in those domains—all of these relationships were forcefully good!

Hurricane Sandy destruction in Breezy Point, N.Y., Leonard Zhukovsky / Shutterstock.com

“But you, keep your head in all situations, endure hardship, do the work of an evangelist, discharge all the duties of your ministry.” 2 Timothy 4:5 (NIV)

On Oct. 28, I was shocked into a cruel reality when I received an urgent text message as I was about to preach my Sunday sermon at Mount Carmel Baptist Church in Arverne (Far Rockaway), N.Y. We were told to evacuate immediately, and that both of the bridges that lead to and from the western portion of the peninsula would be shut down. Hurricane Irene had proven to be a false alarm in 2011, and we mistakenly thought that Sandy would be as well. I instructed all of our parishioners to leave immediately after service. My family and I packed up and headed out to my sister’s place in Bloomfield, N.J.

When I ventured back on Halloween, it took more than five hours to get to Far Rockaway, a peninsula that lies between Jamaica Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. What I saw on the way was sobering, if not devastating: boats in the middle of the street, debris everywhere, no electricity for miles and miles of Queens and Long Island, and homes – hundreds, if not thousands flooded — many destroyed. My own home and church in Arverne took on nearly 7 ft. of water. At Mount Carmel, our offices, fellowship hall, kitchen, and bathrooms were destroyed.

Farm Fresh vegetables & fruits sign, Andre Blais / Shutterstock.com

As a nutrition student in college, I paid attention to the food we would eat on campus and became keenly aware of how much plastic and material was used and disposed of because of the way our food was packaged. It upset me to see so much packaging thrown in the trash every day. I raised concerns with the Dining Services committee and became a staunch advocate for a better recycling program on campus.

That was my first foray into understanding the relationship between the food system and environmental concerns and their consequent impact on health – something that became a much larger part of my life upon graduation, when I read the book The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan and joined a network of dietitians focused on Hunger & Environmental Nutrition.

The more I read and learned, the more I came to understand the sobering facts about the impacts that our industrial food system has on our society. Power in agriculture has become more and more concentrated over the past several decades, leading to many “monocrops” – large swaths of land devoted to growing only one type of crop rather than a diversity of crops that keeps fields vibrant and healthy. We’ve seen unprecedented extinction of species as a result. Artificial fertilizers lead to soil runoff, nitrous oxide emissions, and pesticides polluting our waterways.

American Dream illustration, carlosgardel / Shutterstock.com

We had taught, run, and dreamed together. Our ministries were growing, I was once again flourishing spiritually, but Richard seemed to be stalled. His peers were finishing college, finding jobs and mates, and Richard was hustling to find odd jobs and was being left behind. As we tended the land, I took a risk. I asked him why he had said he did not want a family. He confessed that he had reached that conclusion out of despair. He truly wanted to find a wife and previously hoped to have kids, but he did not have citizenship (his family moved to the U.S. when he was 7 years old) and was not able to find legal, reliable employment. He could not afford to go to college without access to financial aid. He insisted he simply would not start a family that he could not reliably provide for. He had lost hope. But he still had integrity. I was deeply saddened. I was saddened for Richard and his loss of hope. I was also saddened that our community and nation would potentially be deprived of his vision and courage.

U.S. coin motto, I. Pilon / Shutterstock.com

If asked, “what is the most challenging Sunday to preach a sermon?” I suspect few pastors would say July 4th weekend. But as leaders providing spiritual guidance in a country that is often associated with strong nationalistic tendencies, offering a word that speaks to the messy relationship between “God and Country” is a task that American pastors cannot take lightly.

This dilemma of competing loyalties is not new. In both Matthew and Mark, Jesus is approached by opponents who sought to trap him by asking whether they were obligated to pay Roman taxes (Matthew 22:15-22; Mark 12:13-17). An affirmative response would have been a betrayal of faith but a negative answer would be perceived as an act of sedition. Faced with this paradox, Jesus wowed his inquisitors by telling them to give Caesar what was due to Caesar and God what was due to God. Yet, as Franklin Gamwell, notes in Politics as a Christian Vocation, this only raises the question of what belongs to each of the competing authorities. If Christians are called to love God with all our being, then how can anything not belong to God? How can any other authority make a claim of allegiance on our lives?

Pentecost symbol, Waiting For The Word / Flickr.com

All were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, ‘What does this mean?’

Acts 2.12 (NRSV)

Charles Ramsey, the African American male dishwasher who rescued Amanda Berry from captivity preached a transforming sermon when he shared his story about how he helped a Euro American woman in distress escape from 10-years of captivity. Ramsey boldly told the local television news reporter in Cleveland, “Bro, I knew something was wrong when a little pretty white girl ran into a black man’s arms.” And later when CNN’s Anderson Cooper asked Ramsey, how he felt about being a hero, Ramsey said, “No, no, no. Bro, I’m a Christian, an American. I am just like you. We bleed the same blood …”

Ramsey’s blunt honesty which spoke to the existence of racism and his sincere compassion for humanity was a 21st century mystification; a “radical real lived” theological symbol for the reason, why Christians celebrate Pentecost – the birth of the Holy Spirit and the historic beginning of the Christian Church. Biblical scholars teach us on the Day of Pentecost that a strong wind swept through a house where Jesus’ followers gathered days after he was resurrected from the dead. It was in the city of Jerusalem, where Jewish pilgrims gathered to celebrate Shavuot and people from other cultures who spoke diverse languages — believers and non believers of Jesus, heard about God’s powerful works in their native tongues and felt God’s holy presence.

When the day of Pentecost came, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Sprit gave them ability.

Women's Rights National Historic Park statues, Zack Frank / Shutterstock.com

Consider in the past year alone, America has wrestled over the injustice of forced vaginal probe ultrasounds. We have had our own deep cultural apathy revealed as the media tipped their sympathies toward the jocks that ripped a 16 year-old girl’s life and body through gang rape in Steubenville, Ohio – even as our nation gasped in horror at multiple reports of gang rapes of women in India. And over the past few weeks we have witnessed the unmasking of several U.S. military leaders, who were charged with duties to protect the women in their ranks, as they were revealed to be the very perpetrators themselves.

In Jim Wallis’ latest column, he writes, “It’s time for all people of faith to be outraged” and adds, “And it's time for us in the faith community to acknowledge our complicity in a culture that too often not only remains silent, but also can propagate a false theology of power and dominance.”

Will we do it? Will we take the step? Will we allow this holy wind that has blown the cover off of evil deeds done in the dark to rush through? Will we allow the cleansing waters of God to wash our society clean of practices — both private and public — that twist, maim and crush the image of God in more than half its population? Will we exercise the same courage that it took for those women at the first Pentecost to allow the spirit to move them into the public square and speak — testify, tell the truth, and prophesy? Will we repent from our silence?

Repentance begins in the heart. So, I must ask: “Will I repent of my silence — my safe silence?” Yes.

Woman in urban environment, Jose AS Reyes / Shutterstock.com

How do you love your neighbor when your neighbors sell drugs and exploit young women? I’m serious — this is a legitimate question that I am asking myself a lot lately and I am not sure I have the answer.

Nine years ago my wife and I moved into East Oakland to become a part of a small church community called New Hope and to direct InterVarsity’s Urban Project in the Bay Area. We’ve weathered some challenging experiences: stolen cars, physical assault, hearing a lot of shootings, witnessing a shooting, breaking up domestic violence, seeing a friend’s family torn apart by domestic violence, and endless amounts of trash on the streets. Don’t get me wrong, there is a lot to love about our neighborhood and community, but in recent months I think I’ve reached my limit.

The family that recently moved in across the street is friendly. The folks hanging out on the porch and the kids playing tetherball off the street sign honestly do contribute to the vibrant life of the block. But when I saw a total of 12 drug deals go down in broad daylight in the span of three days, loving my neighbor became a lot harder.

Screenshot from Voices Conference website

There is a question that is usually on the hearts and minds of many if not most people who are living and working in missions or active for justice when they attend events. There is an elephant in the room, a funny feeling in our stomach. The question is, where are the people of color?

"Leroy, where are the black people?"

My heart always sinks, as I know my friends who lead these events want nothing more than to see more diversity. I have had many conversations and even disagreements about what the answers may be to how to "diversify.” A few years ago I went to New York to visit my friend Gabe Lyons who I have known for quite a few years now. I went to Gabe because he is a friend, but also because he’s a person with experience in gathering people together. I had this desire in my heart to bring people of color together, specifically black folks. Gabe and I talked for an afternoon and I left there believing perhaps it was time for me to gather black leaders together.

Abstract heart cardiogram, Petr Vaclavek / Shutterstock.com

The common good is not only about politics. The common good is about life and how we live it. It is ultimately about how we are all connected. It is about how our love or lack of love affects our families, our neighbors, our communities, our cities, our nation, and our world.

The common good is about personal brokenness. Have we taken the time to let Jesus come in and heal the wounds that distort the image of God within of us — wounds that drive daughters and sons, mothers and fathers to self-destruction? Have we taken the time to let the Great Physician heal the personal wounds that break families and friendships, slicing the central fabric of society? We are all connected.

Two churches, Silva Vikmane / Shutterstock.com

As Americans, we live in a culture that is hyper-individuated, fragmented, and dehumanizing as it pushes a mantra of success based on material accumulation and power. Being in community with others is the countercultural answer to this. Doing so with others unlike ourselves is an important part of this. At the end of the day, above the polarization and partisanship, there is much we can do to promote the common good together. As Maddie put it at a meeting that brought Christians of opposing social interpretations together, "We may never agree on some issues, but that is not why we're here; we're good people, you're good people, let's do good together."

Immigration Reform Rally on April 10. Photo by Catherine Woodiwiss / Sojourners

Many of the great Christian thinkers throughout our history have seen that goodness, by its very nature, is diffusive of itself. That is, goodness is such that it pours itself out. To the degree to which I am good, I share that goodness with others to the same degree. The doctrine of creation is often seen in this light. God’s goodness is perfect and as such it is poured out naturally and freely to God’s creation. Goodness, in a word, is generous.

While thinking about immigration, I began to ask myself what this feature of goodness implies. How does the fact that goodness is diffusive of itself relate to my treatment of others, and especially to my treatment of those who, through no fault of their own, simply lack some of the basic goods that I have in abundance? Well, the answer seemed fairly obvious. My basic disposition toward my things and even myself must be one of generosity. Now we can argue over the fine points regarding this or that governmental policy, but we must recognize what we have and cultivate a deep desire to share it with others. Sharing our wealth, our food, our clothing is, I think, merely the first step towards becoming generous.

Statue of Liberty, Joshua Haviv / Shutterstock.com

Immigrants are a blessing, not a curse. They are assets, not deficits. I have learned this the hard way after seven years working with the New York City New Sanctuary Movement. We have accompanied 67 people on the verge of detention or deportation, and we have lost only three of them.

These people are restaurant owners — employers. Some run small high tech start-ups; others raise children on their own, grouping with other parents to take care of them. They live under the constant fear of disruption to their lives and constant trepidation about whether their children will be separated from them. Many have been picked up for small offenses, like traffic violations and gone to jail only to luckily be released. But they have still have shown resilient courage, that miracle of guts that keeps them going inside the constant fear and the constant harassment. Immigrants are spiritual and economic blessings, not curses. They are assets, not deficits.

For the past 19 years I’ve worked and lived in inner city East Dallas among very poor individuals and families. CitySquare, the faith-based non-profit that I lead, last year served more than 50,000 different individuals. We work hand-in-hand with low-income people to see life improved and turned toward real, lasting, legitimate opportunity. Our day-to-day work involves hunger relief and nutrition improvement, health care delivery, wellness programs, legal services, housing options, workforce training and job placement, public policy initiatives, and community organizing. It has been in this dynamic context that we’ve become very involved in advocating for comprehensive immigration reform.

Over half of our friends and neighbors who come through our doors seeking a better life are undocumented residents. Since our entire approach to the community is based on building strong, personal connections and relationships across and beyond the typical barriers of income, gender, race, and religion, we’ve become very aware of the plight, the needs, and the rights of our immigrant friends. Tens of thousands of residents of the Dallas metro area need the relief that comprehensive immigration reform promises.

Cup of cold water, Gunnar Pippel / Shutterstock.com

During this time of Lent I’ve been meditating anew what it means to be a follower of Jesus. Interestingly, the only Gospel to contain the word ekklesia — church — is the Gospel of Matthew. Also in Matthew is an interesting take on the call of the disciples. Matthew 10 begins with the premise that as disciples we are all are potentially homeless in a world that has radically different values. Immediately after Jesus calls the 12 disciples, he warns them that they will be misunderstood, mistreated, and often on the road. Then Jesus gives a particular imperative for discipleship. I call it the “cup of cold water” discipleship test. Part of the discipleship marker is hospitality. A cup of cold water is a reprieve, a welcome, a new start.

A cup of cold water is the minimal requirement for what the Scripture calls hospitality or in the original language, xenophilia — love of the stranger. Jesus says that whoever gives a cup of cold water to these nomadic disciples will not fail to receive their reward. Hospitality is a Christian virtue. The writer of the book of Hebrews reminds us, “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers for some have entertained angels unaware.”

Ivone Guillen / Sojourners

Introduction from Lisa Sharon Harper: Every once in a great while you meet someone who carries in their very body the scars of injustice that we talk about so much at Sojourners. These scars leave permanent reminders of the profound need for every follower of Jesus to follow him in word and deed. It is my great pleasure to introduce you to my friend and colleague, Ivone Guillen. As Sojourners’ Immigration Campaigns and Communications Associate, Ivone has worked tirelessly for the passage of just immigration reform for two years. As a formerly undocumented immigrant, she bears the scars of our unjust immigration system and has experienced the healing that came from changes in immigration policy last year. Please read Ivone’s story. It reflects the stories of millions of people in church pews across the country; people made in the image of God, people waiting for that image to be fully recognized and set free inside our borders.

I remember clearly the day I heard the announcement on deferred action for childhood arrivals (DACA) as I felt an overwhelming surge of emotions in that one moment. A path to opportunity, however fragile and short-term, had finally been created for undocumented young people wanting to become full members of American society.

As I sat on the sofa on the morning of June 15 in front of the television and next to my computer, I felt anxious, excited, and dazed at the same time. There I was, listening to one of the biggest announcements ever made in my lifetime, and it directly impacted me. It was a surreal moment since I had been working with the advocacy community for almost two years and had seen difficult developments take place at the state level on the issue. Then and there, I felt that all of my work was paying off and that change could be achieved with enough persistence and pressure. It was a moment that most people wish to live and see, especially those who have worked in the movement for decades but seldom experience the ultimate triumphs of slow processes.

Hand holding smart phone. Chardchanin / Shutterstock.com

The pressure from the faith community on Congress to address gun violence is building. There have been vigils, marches, and press conferences. Faith leaders have visited the White House and lobbied on the Hill. Now, an interfaith call-in day is being organized on Feb. 4 to ensure Congress hears directly from people of faith demanding change. This is a chance for your voice to ring through the halls of Congress.

While the debate on sensible gun restrictions has continued, local evening newscasts continue to run stories highlighting yet more tragic deaths from gun violence. We need more than a conversation. We need Congress to find the courage to lead.

Photo: Empty classroom, Arcady / Shutterstock.com

As the Faith Based Organizer for the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies (FPWA) — a citywide coalition of more than 300 member agencies and faith institutions — I have the privilege of working with a diverse group of faith leaders. Last spring we were thrust into an important struggle for childcare and after school funding led by the Campaign for Children (C4C), a citywide coalition of organizations advocating for childcare and after school funding. Some may wonder why clergy would be concerned about this issue, but for the clergy I work with, the reason is clear: budgets are moral documents, and what is funded reflects our values. Our clergy know that children are the greatest in God’s kingdom and our investment (or lack thereof) in them will have consequences for our future.

In New York City obtaining quality education is a serious struggle for parents of all classes. This struggle includes waiting lists that upperclass parents place their unborn children on, intelligence test for 5 year olds, interviews and hustling from one open house to another. Finding childcare is a daunting task, especially for low-income parents. As a child in New York City I knew how important it was to not end up at my “zone school,” which are schools for children who could not get in anywhere else. Growing up in one of the 12 poorest communities in New York City, my zone schools were the worst. From junior high on I had to take buses and trains to get an education. The process of finding childcare is one of the clearest depictions of the greatest lie that controls New York City: “that some people are worth more than others” (NYFJ Faith Rooted Organizing Core Lie Exercise March 2011).

Photo: Community image, Pavel L Photo and Video / Shutterstock.com

"I expect and am willing to be persecuted, imprisoned, and bound for advocating African rights. And I should deserve to be a slave myself if I shrunk from that duty or danger." -William Lloyd Garrison, Abolitionist (1805 - 1879)

With Black History Month coming up in February, many of us will remember the civil rights struggles that have brought us to where we are today. I recently read a fascinating book about that movement focused on the role of women in those efforts called Freedom’s Daughters. It highlights past generations of women activists, both black and white. They led in the struggles for abolition, desegregation, civil rights, and women’s suffrage. These movements carry with them the roots of our contemporary work for justice.

As I considered the lessons from that book I found myself resonating with many challenges, failures, and victories these women experienced, much of which was based on the race and gender dynamics of the day.

As an educated white woman who began my foray into community organizing though a summer internship in my early 20s — like many of the young women in Freedom Summer coming down from the North — I had not yet delved into the complicated nature of race relations in the United States. I started my summer feeling competent, a person who could learn and adapt to changes as I had on many previous international mission experiences. I carried with me an overly simplified belief in the romantic “beloved community.” The beloved community would come about as we worked together, prayed, and marched.

Person standing out in a crowd, © Leigh Prather / Shutterstock.com

On New Year’s Eve I wrote “The Top 10 things I’m thankful for in 2012” on my Facebook page. Number four was “Clarity of call and message.” A friend asked in a comment below the post: “How in your own life has this played out? I'm at a crossroads here and It's difficult for me to discern this right now … Feel like I'm just drifting.”

Many of the people sitting in pews across America understand what my friend is going through. “Drifting,” that’s how he put it. In fact, I think it’s a question many people are wrestling with in their daily lives. There are so many issues out there. There are so many hills to die on. There is such deep division in our politics and in the church. Wading through the sound bites gets tiring. How can one make sense of it all? It’s tempting to just give up and disengage like the many Christians did in the mid-20th century.

But we cannot.

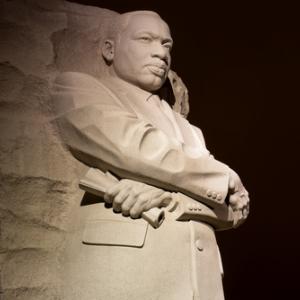

Photo: Martin Luther King, Jr. memorial, Mesut Dogan / Shutterstock.com

As the Christmas season draws to a close, I am reminded of the star that directed the three wise men away from their homeland and into the foreign but welcome presence of baby Jesus. Perhaps this reminds us all that the Divine is constantly moving us into new territory, as stars of all sorts continue to illuminate our path and reset our orientation. The New Year is a wonderful time to search the skies again and see where God is leading us – to check the progress of Church, society, and self, and also see when a new course needs charting. Such a pause allows us to live in our prophetic selves.

As you plan this year – and especially the month of February – remember that the role of a prophet is to, when necessary, provide faithful interruptions or disturbances to the fragile balance of our complex (and often incomplete) frameworks. (That is ONE role of the prophet, anyway). At any given point in the history of civilization we find each of our systems broken – by definition – because humans and not gods have created them.

And while these machinations and paradigms were created to solve society’s most pressing problems and questions, they often serve as coping mechanisms, “band-aids,” and gas canisters that fuel us only to our next checkpoint. You can think of many of these unfulfilled solutions, none of them mutually exclusive: they plague all the sectors of our common life.

The month of February sheds light on one in particular. In the quest for racial justice, we have reached not the finish line but a checkpoint, and we need more prophets.

Earlier this year I spent nearly one week at a Christian university.