Undocumented immigrant families walk from a bus depot to a respite center after being released from detention in McAllen, Texas, July 26, 2018. REUTERS/Loren Elliott

'This Is Not a Crisis. This Is a Long-Term Disaster'

by Sandi Villarreal and Bekah McNeel

Over the past four months, news from the border has chronicled the stories of families detained and separated — many of them seeking asylum from gang violence in Central America. Children as young as 8 months have been taken from their parents and sent across the country to children’s shelters, privately run detention centers, and, some, to foster families. Now, 20 days after a court-imposed deadline, more than 550 children still have not been returned to their parents, at least 300 of whom have been deported.

But that’s not the whole story. News of family separations sounded alarms around the country — and indeed throughout the world — but the humanitarian crisis at our nation’s borders has a long history, and it’s far from over.

Or as one San Antonio pastor put it: “This is not a crisis. This is a long-term disaster.”

"Hope," Catholic Charities of San Antonio's disaster relief truck in McAllen, Texas. Photo by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners

Part One: Getting Here Is Just the Beginning

The heat is unforgiving in the border town of McAllen, Texas. It is here, at Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley’s Respite Center, that recently released migrants find brief relief — along with access to restrooms, a meal, and volunteers who check them in and guide them to the Greyhound bus station down the street. At one end of the center, toddlers climb amid donated toys while a cartoon movie plays in the background.

In mid-July, Catholic Charities of San Antonio (CCAOSA) took its disaster relief truck, “Hope,” on its maiden journey three hours south to the McAllen center, run by Sister Norma Pimentel. The truck, equipped with a kitchen and stocked with 3,000 pounds of food and 400 pieces of clothing collected in the previous 24 hours, was commissioned in the wake of Hurricane Harvey so that CCAOSA could provide on-call aid in the aftermath of natural disaster.

On this day in July, Hope’s mission shifted to man-made disaster.

“We are not treating human beings like human beings. We are treating human beings as animals, as objects,” said J. Antonio Fernandez, president and CEO of Catholic Charities of San Antonio. “I kind of cried [one] day, two nights ago because I saw a man who had not seen his child since Feb. 1. Months. You think about that ... .”

Fernandez trailed off.

The night before, he had been called to a reunification mission at 3 a.m. Even these — the ostensible happy endings to family separations — are stressful moments when a lot can go wrong, he explained. There’s red tape until the end. Government entities are procedural, they are doing their job, and their job is not to tend to human needs. In fact, many times policy and procedure stand in the way.

In 2013, CCAOSA became certified by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which means it has a contract with the federal Department of Health and Human Services to house children who cross the border. Staff and volunteers are accustomed to serving unaccompanied minors, but after the Trump administration’s policy changed this spring, they began accepting children who had been separated from their parents at the border. They were not “unaccompanied,” until made so. In July, CCAOSA had about 30 separated children housed at St. Peter-St. Joseph Children’s Home, referred to as St. PJ’s. Fernandez says he never thought twice about whether taking in the kids would be perceived as complicit in the government’s policy.

“We did not know that all of this zero-tolerance issue was going on and — it’s not that we don’t care, don’t get me wrong — it’s that for us, a child is a child,” Fernandez said. “I don’t care if a child is separated from the families before the border, after the border, or at the border. For us, it’s like, what do we do to treat these people with respect and dignity — and love?”

Volunteers sort donated clothes at the Respite Center in McAllen, Texas. Photo by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners

As the San Antonio team prepared tacos and handed out bottles of water to the clients and volunteers at the Respite Center, Fernandez had his mind on the next week’s work: The administration notified him that CCAOSA was one of four agencies, all faith-based, tasked with receiving reunified families. ICE would be dropping the families off at the organization’s main office downtown San Antonio. The court-imposed deadline for reunifying thousands of families — July 26 — was two weeks away.

What must they be running from?

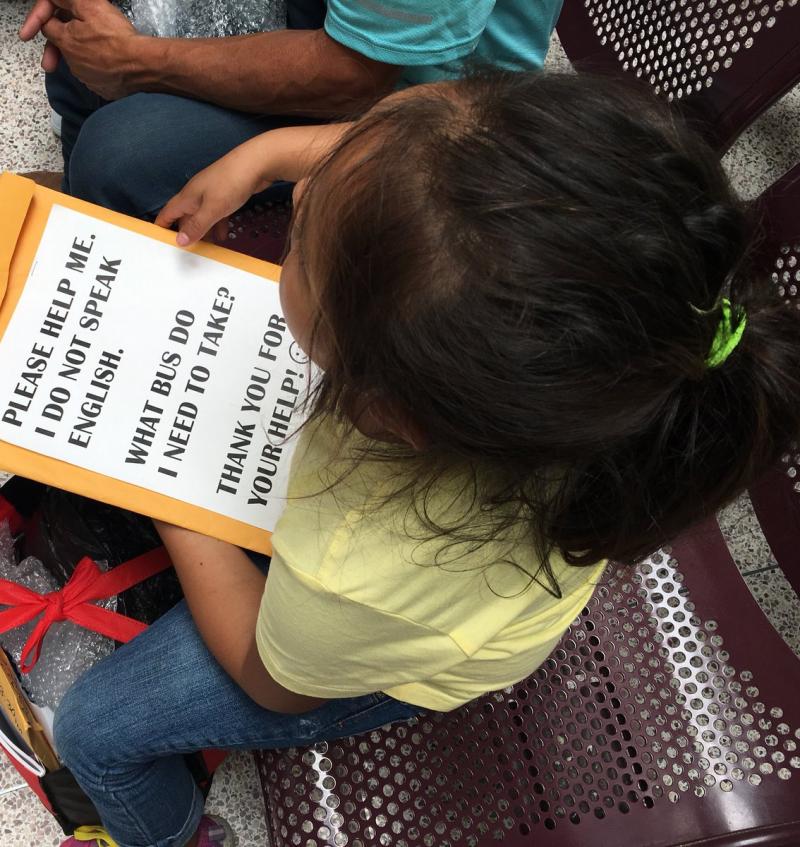

The McAllen Greyhound bus station is about a 5-minute walk from Catholic Charities’ Respite Center. Volunteers escort migrant families, offering translation services and ensuring they don’t miss their buses.

Before some lined up for their bus, volunteer Patricia Mendoza went child to child, kissing each on their cheek or forehead. She and her son came from Austin, about five hours north, to help out. She had seen the news about children who were separated, and asked her priest what she might do to help. The priest led Mendoza to Catholic Charities — and she followed.

“The government doesn’t know what is really happening here,” Mendoza said. “ … [These immigrants] don’t have the same opportunities we have. We are the same.”

While the kids at the Respite Center were not alone — they were with their dads — their plight still moved Mendoza and her son, Daniel Sullivan, who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico eight years ago. Even then, with papers in order and somewhere solid to land, Sullivan said, immigration is an overwhelming challenge for kids. The situations of those he encountered in McAllen were far more challenging, he said, and that tells him that what these children are running from must be unbearable.

“They’re coming here out of need,” Sullivan said.

After a 5-minute walk back to the Respite Center, an entirely new group of about 40 families had arrived.

Left: Patricia Mendoza kisses a row of children as they prepare to leave the McAllen Greyhound bus station. Photo by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners. Right: A child waits for her bus with her father. Photo by Bekah McNeel for Sojourners

Outbreaks of media attention

One of the trickiest things to navigate for nonprofits who handle immigration-related services is the variability of public attention. Last summer, Catholic Charities found itself in the spotlight after the passage of Texas’ anti-sanctuary cities law, Senate Bill 4. Catholic Charities of San Antonio and in the Rio Grande Valley organized church-based “Know Your Rights” campaigns, and coordinated with local advocacy groups and law enforcement — SAPD Police Chief William McManus also spoke out against SB 4 — to create a community-response plan for when the law went into effect.

The summer before, immigration advocacy groups fielded attention from national media when dozens of immigrants who were smuggled across the border were found in an un-air-conditioned tractor-trailer in a San Antonio parking lot. Ten died and dozens more were severely injured. Before that, the swell of unaccompanied minors in 2014 drew national outlets to South Texas.

The challenge in these media flare-ups, CCAOSA’s director of fundraising Christina Higgs said, is carrying on business as usual. These eruptions are not separate crises, she said. They are outbreaks of the same ongoing crisis: political and social animosity toward immigrants arriving from Latin American countries.

When the Trump administration decided that Catholic Charities of San Antonio would be one of only four sites that would receive reunified families, reporters descended on the otherwise quiet office building. Catholic Charities does not have a public relations professional on staff and had to create press protocols in an instant when dealing with reporters from national outlets, Higgs said.

Local and national media outside the office of Catholic Charities of San Antonio. Photo by Bekah McNeel for Sojourners.

During the 10 days leading up to the court-imposed deadline for reunifying families, Catholic Charities hosted reunifications for 44 families. Parents and children continued to trickle in after the deadline, said Higgs, but in the rush to meet it, families were arriving around the clock, some even in the 1-3 a.m. hours.

Yet in the midst of the family reunifications, the ordinary work of Catholic Charities had to continue. While the crying children and bereaved parents won public sympathy, most Catholic Charities clientele have a more complicated story.

Like Honduran Ana Vilma Batiz Martinez and her daughters. They crossed into the United States after the Trump administration had stopped family separations, but because the eldest daughter was 18 she was sent to a separate women’s detention center. Batiz Martinez and her younger daughter, 17, were able to stay together at a family center.

However, it was her older daughter, technically an adult, who was fleeing persecution. She is HIV positive. In Honduras, she was violently harassed because of her status. Batiz Martinez agreed to talk to media because she was worried about her daughter, who would need access to her antiretroviral drugs. She hoped that publicity would enable them to reconnect. But it’s the kind of situation that might inspire as much fear as sympathy, and it didn’t fit the press assignment any reporter in the room had been given. Batiz Martinez’s story never ran in mainstream press.

This is the daily work of CCOSA and similar organizations.

CCAOSA’s work supporting the Respite Center also continues. CEO Fernandez said his team would continue to make trips to McAllen with the disaster-relief truck loaded with donations. His next project: working with other faith groups to purchase mobile showers to station outside the Respite Center.

Part Two: Next Steps in a Long Journey

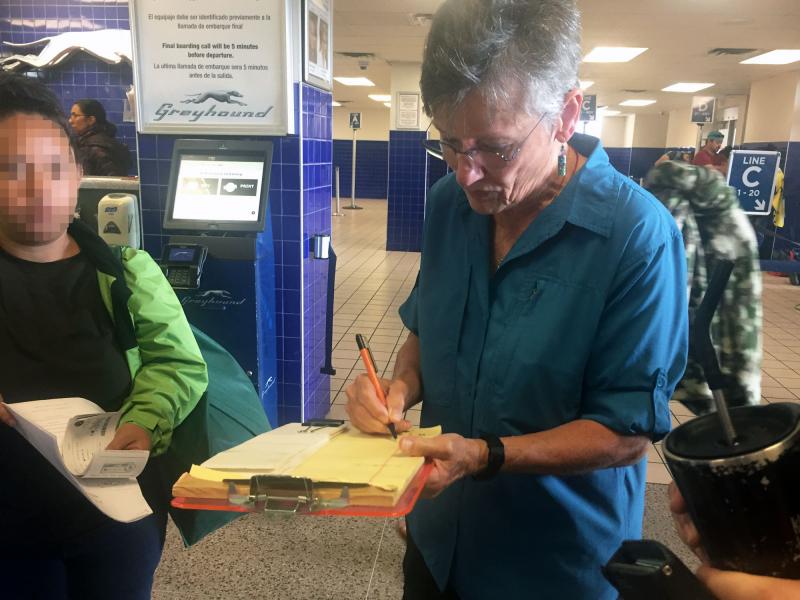

In San Antonio, ICE contractors drop migrant families off directly at the Greyhound station or San Antonio International Airport, often with ankle monitors and awaiting a court date. In response, the Interfaith Welcome Coalition (IWC) formed a sort of mobile respite center. Volunteers meet the families at both locations and provide backpacks with clothes, toys, and hygiene supplies. The IWC volunteers arrive ahead of the detention transports from Dilley and Karnes detention centers and set up shop in one corner of the airport or bus station waiting room — twice a day, every day.

On a Friday morning in July, the ICE transport team dropped off about 35 women and children at the bus station earlier than normal — before the IWC team arrived.

As soon as she arrived, volunteer Jan Olsen jumped into action. Olsen stationed herself near the ticket counter, making a note of each woman’s departure time on a white sticker. She stuck the sticker to each woman’s sweatshirt with a loving pat. Olsen, a Chinese medicine practitioner and former midwife, has mastered the art of gentle command. As she moves around the Greyhound station, everyone knows her.

Left: IWC volunteer Jan Olsen checks in women just released from Dilley Detention Center. Right: The Greyhound bus station in San Antonio, Texas on a busy July Friday. Photos by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners

When Olsen discovers that one woman was supposed to be taken to the airport, she insists that the “trail bosses” — transport contractors with ICE — take her. They aren’t supposed to, but Olsen’s sure they can find a way to make it work. They do.

“Don’t let anybody tell you anything bad about the trail bosses,” Olsen said. “These guys are great.”

Her rapport with the bus station staff is hard won. It has taken a long time, a lot of consistency, and a lot of good behavior to get them to trust Olsen — to let her reserve a corner of the waiting area and to work with her to adjust tickets when an earlier bus is available.

The mothers and children, most wearing plastic rosaries around their necks, look weary. Numb. Given what they are fleeing, the fact that they have been treated with such dispassion until now has to lead many of them to conclude that empathy is unavailable. If fleeing for your life with your 3-year-old in tow does not inspire compassion, then it is reasonable to conclude that it does not exist.

Then, suddenly, it does.

While IWC volunteers pass out toys and food, the women in the waiting area begin to relax. They smile as their kids smile. Still in survival mode, they try to get extra backpacks or lunch packs when they see that there are extras.

Olsen has the unfortunate duty of conserving resources, which are perpetually stretched thin.

“We have just a few left over at Travis Park [United Methodist Church]. We’ve got to get through the weekend, and we’ve got to get through Monday. So if it seems unkind, that’s why,” Olsen said. “I mean, I’d give one to everybody. We just don’t have —”

A woman pulls Olsen’s attention. Olsen hands over a flip phone for the woman to call her mother, then turns to the next task: Olsen pulls out a tupperware container full of over-the-counter medications — cough syrup, throat lozenges, aspirin — and a line quickly forms.

Many of the families picked up sore throats or colds while in detention. A woman asks for one gingerdrop for her son. Olsen folds two into an envelope and hands it to her.

fullsizerender.jpg

for their route are sold out. They'll return to

Dilley Detention Center. Photo by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners

After a 20-minute scramble, the group settles. Then the departure is called for the first mother and child to board their bus. The group breaks into smiles and claps to send them off.

It didn’t work out that way for another woman. She held an open ticket, but her route was sold out on that busy Friday. She and her young daughter were returned to Dilley Detention Center to wait for another opportunity.

Taking over the narrative

Public outrage now wanes in the aftermath of the Trump administration’s failed policy of using family separation as a deterrent. The court cases between the administration and the ACLU continue. But the administration now has set its sights on other limitations to immigration:

- Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced in June that gang violence and domestic violence no longer meet the criteria of credible threat for seeking asylum in the United States.

- The administration had already more than halved the cap for refugee admissions to 45,000 for fiscal year 2018, a number it is not expected to meet, and reports indicate the cap could be reduced to 25,000 for 2019.

- The administration has ended temporary protected status for Salvadorans, Hondurans, Sudanese, Nepalis, Nicaraguans, and Haitians, totaling about a half a million people, and giving the groups about year to leave the United States.

- Reports indicate the administration plans to unveil a proposal that would make it harder for legal immigrants to get “green cards” (proof that its holder is a lawful permanent resident) or become citizens if they ever participated in certain welfare programs.

Trump and his team have successfully established a negative narrative on immigration for his political base — indeed Trump’s approval ratings and support for his immigration policies are identical.

Evelyn Martinez Huron, an immigration attorney and the director of CCAOSA’s Caritas Legal Services, acknowledges that immigration in the United States feels chaotic. But she points out that the actual laws governing immigration — those set by Congress — haven’t changed in decades. What has changed, she said, is how the laws are implemented. It is the executive branch who decides how the laws are enforced, and most presidents create and enforce policy to accomplish political — not practical or humanitarian — goals.

“Part of campaigning and rallying is creating this atmosphere of fear,” Martinez Huron said, and politicians are always campaigning.

President Barack Obama created a political picture of the United States when he issued the executive order that established Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). President Trump has done the same when he instituted the family separation policy. Trump’s characterization of Latin American immigrants as “rapists” and “criminals” has changed the national conversation in a way that makes it far more likely that immigrants will encounter suspicion and hostility, Martinez Huron said.

“All of the sudden it’s ‘Is that really who we’re letting in?’”

John Garland, pastor of San Antonio Mennonite Church, wants to change that narrative, particularly among center-right pastors and people of faith. Earlier this summer, Garland made a series of trips to both sides of the border, shooting video from the bridge where asylum seekers were being turned away and meeting with ministries in Reynosa, Mexico, across the border from McAllen, Texas.

John Garland, pastor of San Antonio Mennonite Church, talks about the myths associated with the narrative around immigration in his office in downtown San Antonio. Photo by Sandi Villarreal / Sojourners

“The real danger is the way we are perceiving these people,” Garland said. “… I feel like we need to give testimony to what's going on. I'm not going to invest loads and loads of time in trying to change the mind of a pastor. I think what we need to do is we need to tell the story truthfully and we need to model the behavior and let God do the conversion stuff.”

San Antonio Mennonite lends out office space for a pro-bono immigration attorney, and offers emergency shelter for released immigrants as needed. Garland also produced an informational report sifting truth from myth in different immigration situations, from family separations to unaccompanied minors to the families sleeping on the border bridge seeking entry into the U.S.

There is, of course, the myth of the perfect immigrant. Much like victims of sexual assault, which many of these migrants are, there is no single immigrant story that fits neatly within a certain framework. People who have experienced extreme trauma, especially people who fear for their lives, nearly always provide inconsistent stories, which works against them in the asylum process.

It’s also a myth, said Martinez Huron, that families released wearing ankle monitors disappear and “we never see them again.”

“Yes … you do,” she said. Martinez Huron sees them in her office. Detaining asylum seekers while they await their court case is immensely impractical, she said, because asylum seekers have a full year to complete their asylum application once they have cleared their credible threat interview.

Martinez Huron bristles at the phrase “the law is the law.” She hears it a lot. As someone who works with the law, she’s well aware of what the law is and is not.

“Well you know what?” she said, “There are certain things that are against the law, and as a people we decide those laws don’t work for us anymore.”

Touchpoints on a sacred journey

Navigating bus routes and cross-country travel with limited knowledge of the language is difficult. From San Antonio, some families had two or more connections: Dallas, Nashville, Cleveland. At the other end waits a sponsor — typically a relative.

In Texas, an underground railroad of sorts began to help immigrants navigate their journey. The network connects released immigrants with immigration attorneys who guide them through the legal process.

Launched during the family separation crisis, Together & Free is a network of volunteers across the country that serves reunified families as they adjust to their new communities. Volunteers work with organizations such as RAICES, Annunciation House, Grassroots Leadership, and others to offer a variety of support services to more than 150 families.

The Southern California chapter of Matthew 25 network includes more than 200 churches who offer training and resources to accompany immigrants to ICE appointments, emergency shelter, advocacy, and for some, physical sanctuary within church buildings.

The New Sanctuary Coalition, Sanctuary DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia) and other local and national groups bridge the gap between on-the-ground services, public education, and advocacy at the national level toward policy change.

“It's like this is a sacred journey these families are on — no matter how wounded they are or broken, but that is the sacred story — and we get a chance to touch it,” Garland, pastor at San Antonio Mennonite Church, said.

We're following the story. Make sure you're up to date on the latest.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!