There have always been two Americas: that of rich and poor, of inclusion and exclusion. The America of inclusion found expression in the ideal of “liberty and justice for all,” and has been embodied whenever Indian treaties were honored, and in the embrace of civil rights, women’s suffrage, or child labor laws. The America of exclusion, on the other hand, was articulated in a Constitution that originally enfranchised only white landed males and has been realized in land grabs, Jim Crow segregation, Gilded Age economic stratification, and restrictive housing covenants.

These two visions of America continually compete for our hearts and minds, not least in our churches. On one side are the voices of Emma Lazarus in her poem “The New Colossus” (“Give me your tired, your poor...”), and Martin Luther King Jr. when he preached “I Have a Dream.” On the other side are those of George W. Bush’s imperial politics and James Dobson’s “Focus on the Family.”

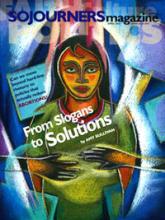

Perhaps the most consistent battleground between the two Americas, from inception to the present, has concerned immigration. Where our churches locate themselves on this political and theological terrain is profoundly consequential.

All social groups establish boundaries—whether physical impediments, such as fences or borders, or symbolic and cultural lines, such as language or dietary laws. Such boundaries can be a good thing, especially when they help protect weaker people from domination by stronger people. More often, however, boundaries function in the opposite manner: to shore up the privileges of the strong against the needs of the weak. It is this latter kind of boundary that characterizes the current U.S. immigration debate and that the Bible consistently challenges.

Read the Full Article