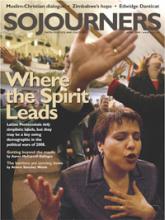

The enigma of Latino Pentecostals is found in their ability to resist labels and simple classifications. Or maybe it’s just that most people’s assumptions about them are all wrong? Either way, Latino Pentecostals have been ignored, misunderstood, and mislabeled for too long.

The Latino community has functioned almost undercover for many years, hidden for the most part from the eyes of mainstream society. In The Labyrinth of Solitude, writer Octavio Paz calls the “masks” that Mexicans and other Latinos wear in society “a wall that is no less impenetrable for being invisible.” The image of Latinos in mainstream U.S. society is as unfocused as our ability to agree on what we will call them—Latino or Hispanic, Chicano or Boricua. The name we choose for Latinos tells us more about ourselves us than it does about them.

Pentecostals, too, are unknown, even suspect to many. People don’t know what to make of their unknown tongues, miracles, or outlandish holy roller ways. Pentecostals from Aimee Semple McPherson to Pat Robertson are partly to blame for this—with a striving to be in this world but not of it that sometimes borders on the bizarre and sensational. Most Pentecostals, however, deserve more down-to-earth reputations. By preaching that everyone has a right to enter into direct contact with God regardless of their education, race, or class, Pentecostals have become the fastest growing Christian movement in the world today.

Read the Full Article