From her earliest years, Dorothy Day has believed that the place for people to be is on the barricades. She has been there with them.

As a young journalist, she shared empathetically in the despair and the hopes of the poor. She joined forces with those who championed the cause of the oppressed in the early 1900s -- communists, socialists, anarchists, and others. In 1917 she went to Washington to protest with the suffragettes, seeking the right of women to vote. The trip resulted in the first of several jailings for her beliefs.

Dorothy Day’s pilgrimage sent her searching for more transcendent solutions to questions that the ideologies of that day left unanswered. She was drawn to the wisdom of the church, reading such works as The Imitation of Christ by St. Thomas a Kempis. Then, through circumstances whose workings are ultimately a mystery, Dorothy Day was converted and baptized as a Catholic.

Her heart remained with the poor; her politics were deeply imbued with a growing radicalism; her passion for justice now put down roots in the transcendent.

In 1932 she marched on Washington once again, this time with the hungry and the unemployed. In her simplicity of spirit she asked why the church was not leading the cause of those who were without food and work. And she prayed for a chance to work on behalf of the poor.

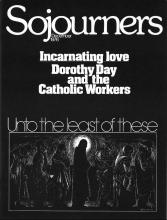

At the end of that year she met Peter Maurin. It was a “providential” encounter, she said. Together they grasped how the gospel was at the heart of their commitment to the poor, motivating their advocacy of radical social change. The 34-year-old Catholic Worker movement was born out of this shared vision.

Dorothy Day is meek. She rehabilitates the meaning of that biblical word.

Hers is a genuine humility. There is a modesty about her, a simplicity of spirit. All this is undergirded with profound inner strength and clarity of purpose.

Read the Full Article