"Who was Brezhnev?” a Russian child of the future asks his grandfather in a contemporary Soviet joke. And he responds, “A minor politician of the Solzhenitsyn and the Sakharov period.”

Perhaps the day will come when a child will ask, “Who was Billy Graham? Who was Pope Paul?” And the answer may be, “Minor religious figures of the Dorothy Day period.”

Dorothy Day wouldn’t approve of the joke, of course. For one thing, she has great appreciation for Pope Paul. For another, she doesn’t want to be burdened with admiration. “Don’t call me a saint,” she fired back at one starry-eyed soul, “I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.”

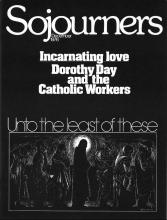

Nor would she appreciate being torn from her context, the Catholic Worker movement. For others, that movement is incarnated in her; in her own vision it is nothing more than an awkward but necessary expression of the practical life (and the hard sayings) of Jesus. She would emphasize, without a trace of false modesty, the founding role played by a wandering scholar from France, Peter Maurin. She would talk of all those who have come into the Worker community over its 43 long years.

And yet her friends and co-workers know, in both love and bruises, the Catholic Worker movement would be a very different thing, if it existed at all, were it not for the volcanic stubbornness of Dorothy Day.

Apart from that religious stubbornness that has become such a signature of the Catholic Worker movement, it is unlikely that contemporary Christianity would be dotted with so many occasions of hope, so many communities dedicated to the works of mercy and of peace, as many lives so closely centered on the simplicity, poverty, and vulnerability of Jesus.

Read the Full Article