It has become our tradition at Sojourners to focus each December on someone who has taught us the meaning of the incarnation. We have remembered Dorothy Day's stubborn faithfulness and Fannie Lou Hamer's strength against all odds. Clarence Jordan's Cotton Patch gospel and Thomas Merton's monastic radicalism have been gratefully recalled.

One year we profiled Karl Barth, who shocked German liberalism with the reintroduction of a genuine biblical theology. Barth, with his faith solidly grounded in the Bible, became the author of the Barmen Declaration, a manifesto of the Confessing Church's resistance to Nazism.

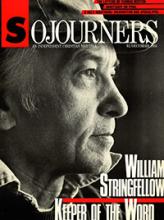

It was on Karl Barth's famous trip to the United States that he noticed a young attorney from New York's Harlem. "This is the man America should be listening to," said Barth. The man who most impressed Karl Barth on his U.S. visit was William Stringfellow. Karl Barth was certainly not the only one on whom Bill Stringfellow made a lasting impression.

I met Bill at a conference at Princeton Theological Seminary in 1971. The conference organizers had invited both of us to speak and wanted us to meet. Our little group of seminary students in Chicago had just begun publishing the Post-American, the forerunner of Sojourners. I'll never forget that first time I heard Bill speak.

He talked very quietly, and, at times, I had to strain to hear him. And yet there was a force and power in his words, an authority I had never encountered in anyone before. He always spoke from the Bible, and, from my first hearing of William Stringfellow, I felt that the Word of God was being opened up to me. The way he explicated the scriptures caused a deep excitement within me.

Read the Full Article