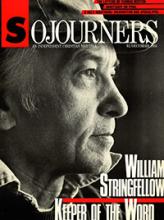

Bill Stringfellow "died," whatever that means, in March. "It happens," Bill would say, "I've been [working on that." His visits to our home in Berea, Kentucky, were frequent in the last few years, the evenings spent in conversation with Nancy, my wife, about the latest "monstrosities" in medicine, for their experiences overlapped. The last visit he was taken by the "passion" for the artificial heart. He'd thought a lot about it, probably made notes somewhere on hotel stationery.

Unlike his speech in formal settings, and his characteristic one-or two-liners, he talked at length informally, sometimes in monologues about the first drafts of books and articles, or people and politics. Knowing he'd be with us in the spring semester the following year, it never occurred to us to take notes. It is my hope that Bill's notes will turn up someday, somewhere.

I tell this to introduce Stringfellow's consistency during the 25 years we knew each other—he had the gift of grace to integrate experience, language, and suffering with the word of scripture. Last December when Bill visited, he was weak and the old maladies persisted, but Nancy, my colleagues, and I never thought he would not return as Visiting Lilly Professor of Religion, spring 1986. He had been through decades of physical nightmares, which he discussed as dispassionately as he did baseball or the weather.

Read the Full Article