Mine is a very personal approach to understanding William Stringfellow's witness to the church in our day. The encounters he and I had over the last six years were important to both of us, I believe. He was involved in my own struggles as an elderly woman seeking ordination, and my difficulties pointed up for both of us the multifarious facets of both sexism and ageism. We also met over a variety of concerns having to do with justice and peace, and we shared a lively sense of irony and creative absurdity that brightened the times of relaxation among friends.

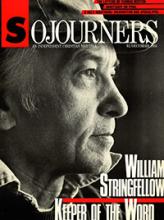

Among the good memories is his inconspicuous entry into a seminar room in which he was to speak. Not having what you would call a commanding physical presence, Bill would simply take his place and look at his notes and the audience until it fell into a silence to match his own. Those who knew him would become still at once, knowing that his words would at times become almost inaudible.

But even without speech, Bill compelled attention. His eyes were arresting in their power, for they searched out the faces before him and drew his hearers in. I puzzled over the emphatic response he drew from others as well as myself, for he seldom raised his voice and was sparing of gesture. But there was lightning in his eye and thunder in his voice when on the rare occasion he let loose to emphasize what he was saying.

A bell rang inside me when I found a statement in one of Bill's books: "I am the most passionate person I know." Why, of course he is, I thought. He doesn't have to overdo it; it is just there for him. He reaches out from the solitary spaces in his heart and touches all of us in our own solitude. If there are any dry bones among us, they are then knit together, and now they stand up, and they live.

Read the Full Article