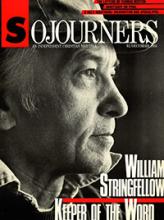

When I think of him, I first think of his Bowery face, a face that seems to have passed through holocaust—whiskered, skin thin on the bone, eyes that have taken in much death and suffering, and yet eyes sharp and quick. At his home, in the years when I lived in New York as a member of Emmaus Community and saw him on Block Island from time to time, he seemed to wear a bathrobe more often than any other piece of clothing. His legs were as bony as his face, and his words were as lean as his legs. Not an ounce of fat in thought, word, or writing.

Bill had passed through death, his own, going into an operating room with the near certainty that he would die on the table. But a very clever doctor saved his life and gave Bill what he called his "second birthday." He had already become well-known for his commitment to the living, especially the afflicted such as he had come to know in East Harlem. But after that experience of death and re-birth, he seemed to connect more than ever before with what might be called the "life movement," rather than the peace movement, since in that phrase "peace" seems to be an amazingly vague and abstract word.

What did I learn from him? More than I will attempt writing here. Something about idolatry, that first of all. Bill made me realize that idols are not only things of wood, stone, or metal that primitive people pray before, but rather that we live in a world, and in a church, crowded with idols, the main one being the national flag. Many of us offer it our own lives and even frequently offer it the lives of our children.

We worship money, status, security, race, and church—various borders of position, belief, and power. Stringfellow, perhaps because of his Lazarus experience, made it easier to live without these standard, everyday modern idols.

Read the Full Article