I spend most of my life now with the Bible, reading or, more precisely, listening. My mundane involvements—practicing law, being attentive to the news of the moment, lecturing around the country, free-lance pastoral counseling, writing, activity in church politics, maintaining my medical regime, doing chores around my home on Block Island—have become more and more intertwined with this major preoccupation of mine, so that I can no longer readily separate the one from the others.

This merging for me of almost everything into a biblical scheme of living occurs because the data of the Bible and one's existence in common history is characteristically similar. One comes, after a while, to live in a continuing biblical context and so is spared both an artificial compartmentalization of one's person and a false pietism in living.

—Instead of Death

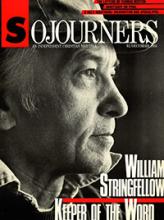

On the altar with the elements of the Eucharist that celebrated his death and life, Bill Stringfellow's New Testament was carefully placed. In the course of that service of memory on Block Island, it had been brought forward by a friend at the offering of gifts.

Many people would smile to recognize the well-worn, by all appearances fragile, book held together by assorted layers of red plastic tape. All who had studied or reflected or listened with him to the scriptures in years past, and smiled to recognize the Word of God, were now invoked like a community with the communion of saints at that sacramental meal.

Stringfellow had traveled far with the Bible. This one, in particular, was a gift in 1946 "from Aunt Polly and Uncle George," and he once confided that it was this Bible that he read and reread "in order to keep my sanity" while a supply sergeant on duty with U.S. NATO forces in Europe during the early '50s. "Reading it effectively prompted my conversion."

Read the Full Article