TOWARD THE END of the film documenting the performance of Aretha Franklin’s album Amazing Grace, the singer sits at a church piano. Like so many times in her childhood, she begins playing — gradually, almost tentatively — the opening chords to “Never Grow Old.” It was her first single, released when she was 14. As she sings of “a land where we’ll never grow old,” built by “Jesus on high,” folks in the audience — including gospel pioneer Clara Ward — cannot help but get up and dance. “Never, never never” — and then a Franklin trademark: mmm-mmm-mmm — “never grow old,” she testifies. You believe her.

This year, Aretha’s Amazing Grace turned 50. The album — recorded live at New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles with James Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir and one of the greatest backing bands in all of pop music history — blends and crosses boundaries of genre, generation, race, and class. In 1972, Amazing Grace was not just a return to Aretha’s roots, but a vision of a future — one rooted in the Black experience in the U.S.

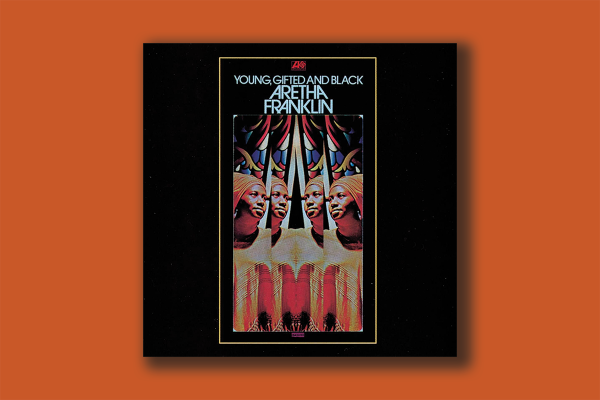

The liner notes credited Gene Paul as “assisting engineer.” Today, he is a legendary producer. Paul traces the genesis of Amazing Grace to Aretha’s 1972 record Young, Gifted and Black. That album’s title track, penned and first sung by Nina Simone, was a breakthrough in the civil rights and Black pride movements. “In the whole world you know / there’s a million boys and girls / who are young, gifted and Black,” the lyrics proclaim. While recording Young, Gifted and Black, Paul told Sojourners, Aretha began to conceptualize the live recording of a gospel album as a follow-up. When she thought of the potential project, Paul said, she “was smiling, captivated.” To Paul, there is a clear through line from Young, Gifted and Black to Amazing Grace: The former spoke to the contemporary Black political moment; the latter looked back in time while pulling her spiritual and cultural roots into the present. Both pointed the way to a Black future that was joyous and free.

Read the Full Article