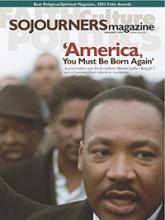

Martin Luther King Jr. made his first public statements against the Vietnam War in the summer of 1965. But harsh attacks from the White House and the press, coupled with lack of support from most of the civil rights community, initially led King to downplay his anti-war stance. After nearly two years of wrestling with the issue, however, King could no longer stay quiet, and he plunged deep into the difficult and controversial work of drawing out the connections between war, racism, and poverty. This excerpt from the forthcoming book To the Mountaintop: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Sacred Mission to Save America, gives a glimpse of King's transformative journey.

The stormy spring of 1967 marked a turning point not only for Martin King, the anti-war movement, and Lyndon Johnson, but for the nation and the world. Vietnam was the axis around which the whole planet seemed to be seeking new directions, new ways out of darkness. The coming 12 months would draw a dividing line in world history as critical as any in the 20th century.

Amid the vertigo of events, King may not have known whether he wanted one movement or two, or what their relationship ought to be. His double consciousness allowed him to see the peace and justice movements as both separate and combined; it depended partly on the audience he was speaking to. For several weeks in April and May he felt called to lead both movements. The dramatic entrance of the most prominent American to oppose the war had energized the movement like nothing else. Many thousands marched in

Read the Full Article