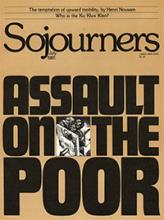

The Ku Klux Klan, low-profiled for the past decade, is now rising again. In the half-moon from central Texas eastward to the Atlantic and up into Virginia, the ugly signs are all there: quasi-secret meetings ("Dens now forming, be there"); open rallies and marches ("Come downtown Saturday to show the Commies some American spirit!"); a flood of literature ("The Ku Klux Klan Is Watching You--Fight For White Rights!"); KKKK (Knights of the Ku Klux Klan) signs marking the roads in the moody, red-clay hill country of Mississippi; crosses burning on the darkened outskirts of Southern towns and cities; astonishing Klan political support in some areas; threats levied--and violence and sometimes death in the Greensboros, Chattanoogas, Okolonas, Wrightsvilles, and Decaturs.

If many people of good will are dangerously oblivious to this upheaval, there are many others who are not. Cries of "Kill the Klan!" abound in some quarters. Calls for legislation outlawing it are rife. The Klan is labeled by some as an outgrowth of American fascism and, by others, as the prime Nazi spearhead. "Scum" and "beasts" are two epithets that seem especially popular among some Northern liberals, while the KKK's critics in the South often prefer to imply Satanic motives.

Anyone who minimizes the dangers posed by the Klan or comparable groups is being, of course, substantially less than realistic. But someone who misses the people part of it is way off base.

On a cool fall night in the mid-1960s, I stood in the shadows of thick Southern pine trees and, with several black colleagues, watched a Klan rally 300 yards away in a cotton field. It was illuminated by floodlights hooked to generators on flat-bed trucks--and by three large burning crosses.

Read the Full Article