IN MY OWN interreligious instruction, I have become aware of the lack of discussion of Indigenous traditions. The very way knowledge is conceived of is at play here. Margaret Kovach articulates an Indigenous epistemology in her essay “Emerging from the Margins” as “fluid, non-linear, and relational. Knowledge is transmitted through stories that shape shift in relation to the wisdom of the storyteller at the time of the telling.”

As I have engaged Indigenous communities and scholarly voices in my work, I have sought to:

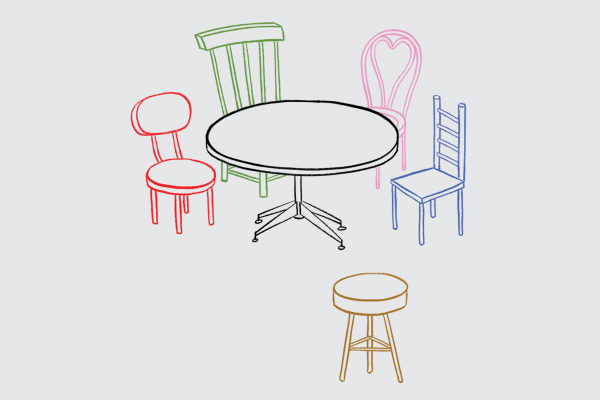

Bust up the category of religion. By this I mean I try to interrogate how interreligious encounters define religion and who is invited to the table, or what parts of a person we invite.

Since I teach at a Christian seminary, religion as defined by doctrinal and scriptural sources takes precedence. I found that many of my Christian students—for instance, those from Tonga—had a deep connection to Indigenous practices woven into their identity. But at seminary this aspect was reduced to “culture” and not given a place at the table. I learned to ask students to self-identify and opened the space to recognize that all forms of their spiritual practice were valid sources of scholarship. They were not asked to cancel or erase parts of their spiritual practice that were considered by others as less important.

Read the Full Article