Jim Forest, a Sojourners contributing editor, is coordinator of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation in Holland. He interviewed Fr. Chacour in early June, 1980, in Galilee.

You won't find it on the map of Israel unless the map is a remarkably good one, but if you draw a line between Haifa and the western bulge of the sea of Galilee, Ibillin is a quarter of the way from Haifa. This village of 5,500 Palestinians is atop a mound that, were you to dig through it layer by layer, would tell the story of life and faith in this contested land back to very ancient times. But the face of the past is largely buried, apart from a bit of a Crusader castle wall that was unearthed a few years ago when the villagers were building a community center.

Yet there are living monuments: the olive trees with their silvery gray-green leaves and gnarled, cratered trunks. Some on the hillside just south of Ibillin are more than 2,000 years old. It may be that Jesus, his family, and disciples ate olives from these ancient trees that, well-tended across the centuries, are still producing fruit.

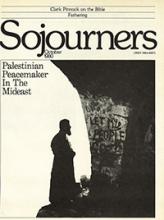

Ibillin is a Christian and Moslem town. Two thousand of the villagers are Moslem, 3,000 Greek Orthodox, and 500 Melkite (Roman Catholics of the Eastern liturgical rite). The Melkite priest, a man well known throughout Galilee, is Fr. Elias Chacour. He is a gray-robed man in his middle years with a thick, jutting black beard, piercing gray eyes, and a contagious energy.

Chacour doesn't fit either Christian or Palestinian stereotypes. A Palestinian who well understands the anger that occasionally leads to violence on the part of the Palestinian minority in Israel, an anger he shares, Chacour is a pacifist. Again and again he draws attention to a talk given some centuries ago on a hillside not far from Ibillin--the Sermon on the Mount.

Read the Full Article