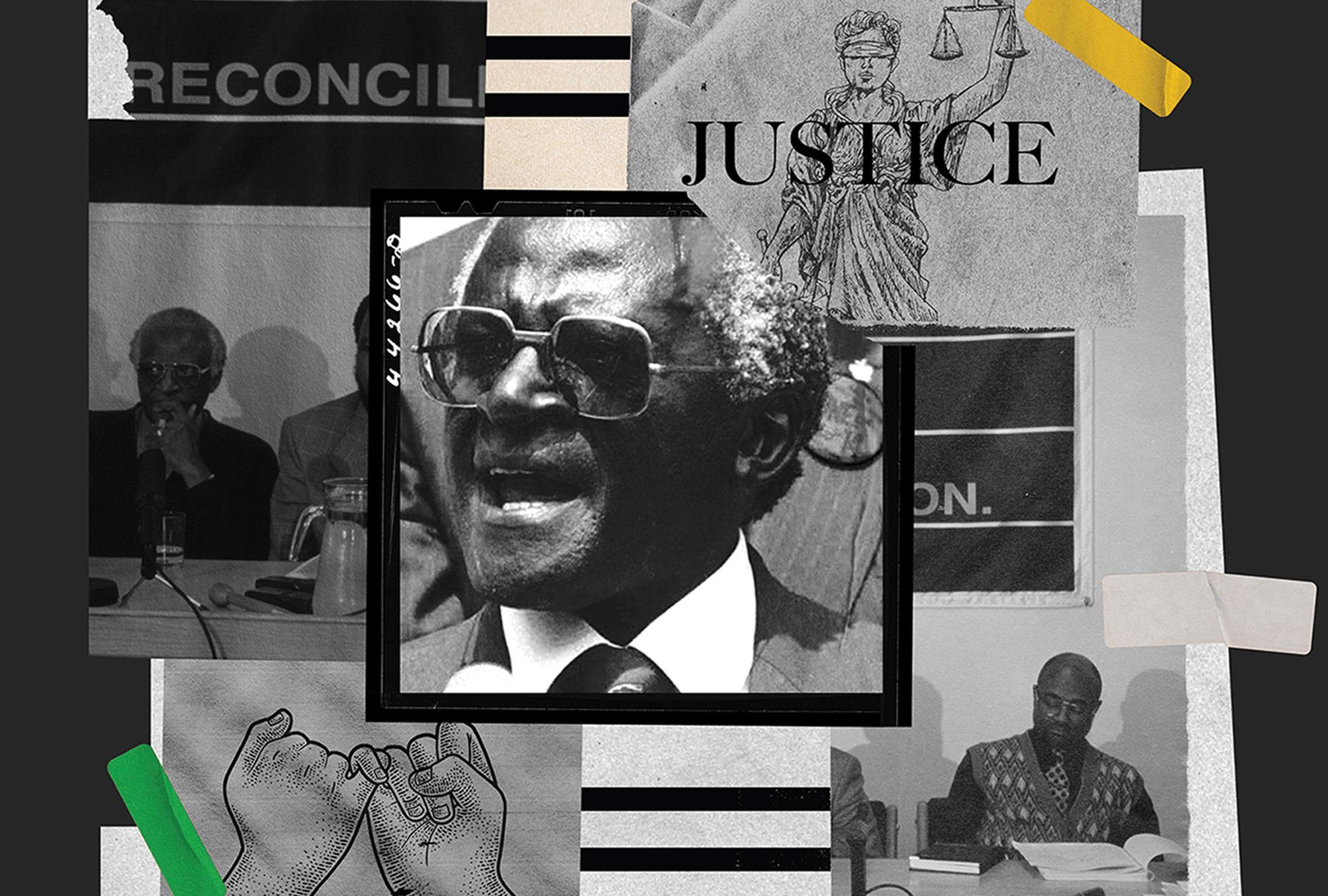

Photos from a South African Truth and Reconciliation press conference / Alamy / Library of Congress / Illustrations by Mark Harris

To Tell the Truth

ON A SUNDAY MORNING in Atlanta in April 1899, white churchgoers, dressed in their finest, filled the pews to hear the word of God. As the postlude concluded, the congregants poured out of their houses of worship, bought sandwiches for lunch, and crammed onto trains heading toward Newnan, Ga., to watch the gruesome extrajudicial murder of Sam Hose.

Hose, a 21-year-old Black farmhand, had been pulled off a train by a white mob and was later murdered while thousands watched his lynching. “‘Sweet Jesus!’ Hose was heard to exclaim, and these were believed to be his last words,” writes Philip Dray in At the Hands of Persons Unknown.

The relationship between religion and injustice in the United States is complicated. U.S. Christians tend to emphasize the role of Christianity in contesting injustice, while forgetting images such as churchgoers going seamlessly from worship to an extrajudicial execution.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the U.S. witnessed the largest protests in our history. This new moment in the long movement for human freedom arises in response to high-profile police and white vigilante killings of Black men and women; it demands an end to police violence and redress for centuries of racial injustice. This “reckoning” has pushed local, state, and national efforts to reform police practices, hold individual police officers accountable for abusive violence, repair the injustice caused by policies such as redlining, and establish the truth about lynching.

As in the past, there has been backlash to this movement, animated predominately by white Christians. Today, some want to ban discussion of race and racism in classrooms and in church. Then-president Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13950 to remove “divisive concepts”—such as that “the United States is fundamentally racist or sexist”—from all federal literature, contracts, and speech. Critical race theory (CRT), a body of legal scholarship that examines how institutions such as law empirically operate in ways that maintain racial inequality, has become a particular target for the Southern Baptist Convention (as well as for Republicans in several states, such as in Tennessee where Gov. Bill Lee signed a bill banning the teaching of CRT in public schools). In response, some Black pastors publicly severed ties with the Southern Baptist Convention. As pastor Joel Bowman put it, “I can’t sit by and continue to support or even loosely affiliate with an entity that is pitching its tent with white supremacy.”

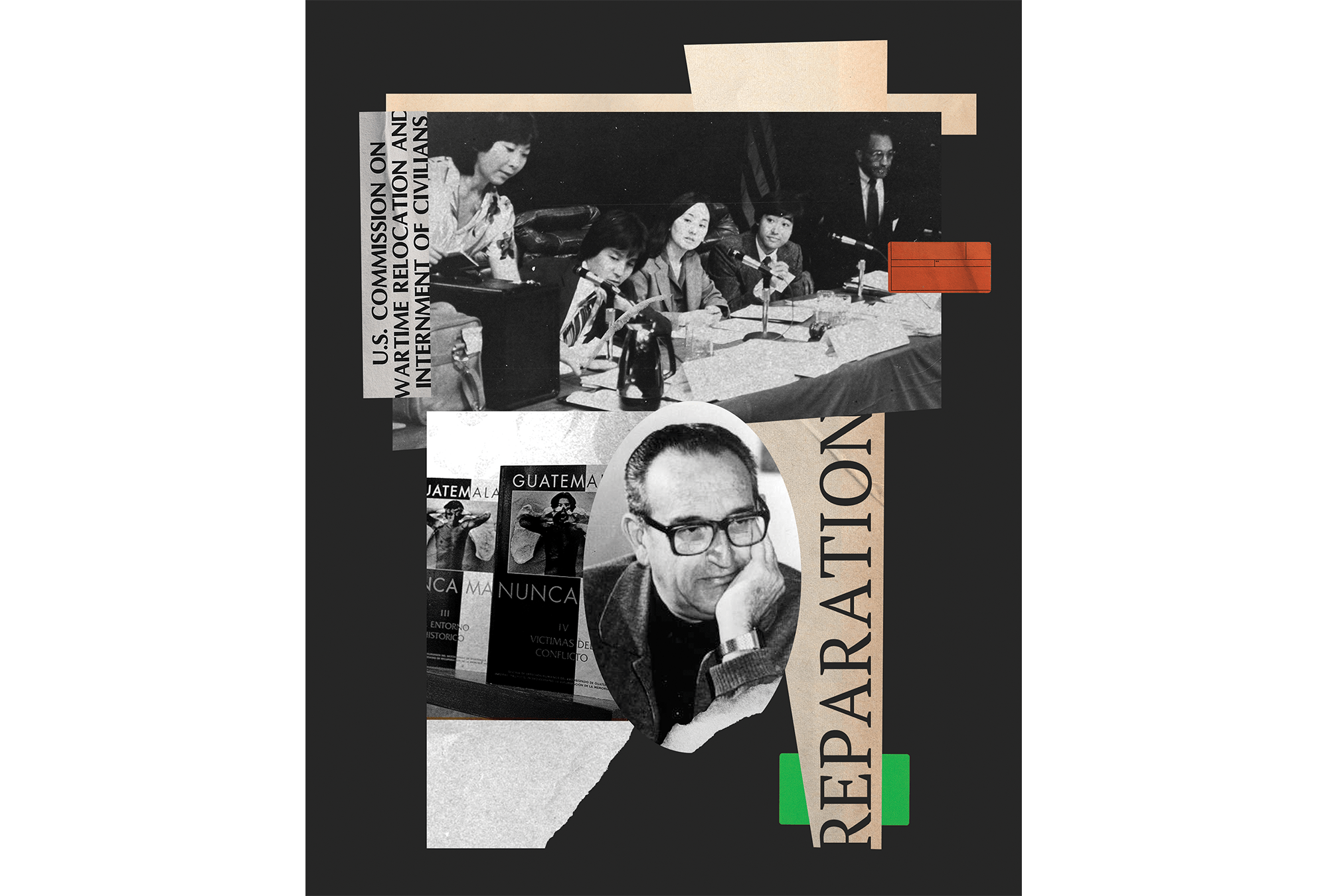

Top, a hearing of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, 1981 / National Archives. Below, a 1998 report on the victims of the Guatemalan Civil War was released by Bishop Juan Gerardi two days before he was assassinated / ODHAG

A background of inequality

THE INTERSECTION OF religion and race in the United States is complicated. It pulls in opposing directions—revealing deepening divisions in the U.S. as well as countervailing calls for unity.

In this context, efforts led by Rep. Barbara Lee are underway to establish the U.S. Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation (TRHT, or truth commission) “to properly acknowledge, memorialize, and be a catalyst for progress toward jettisoning the belief in a hierarchy of human value, embracing our common humanity, and permanently eliminating persistent racial inequities.” In an April letter to President Joe Biden, some Christian religious leaders, including from Sojourners, requested an executive order to establish a truth commission to “examine the systems in place that lead to the disenfranchisement and marginalization of Black people and [to] shed light on the legacy of institutional racism and how it continues to impact every aspect of American life.”

The theory and practice known as transitional justice provides invaluable resources on which the truth commission movement can draw. The starting point of transitional justice is that the repair of damaged relationships requires that wrongs be acknowledged and redressed. From the perspective of transitional justice, attempts in the U.S. to silence speech about white supremacy, critical race theory, and systemic racialized abuse are ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Silence will not end racism or heal the deep divisions and fractures in the United States. Burying history does not remove the impact of historical wrongs on contemporary relations.

In recent decades, more than 40 countries have heeded the central insight of transitional justice, establishing a wide range of processes to address widespread wrongdoing. Transitional justice was a central part of the transition from communism to democracy in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s, from apartheid to multiracial democracy in South Africa in 1994, and from conflict to a commitment to peace in 2016 to end more than 50 years of warfare between the Colombian government and the Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia.

Processes of transitional justice take many forms. Domestic, international, hybrid, and ad hoc criminal trials have held perpetrators to account for human rights violations. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and a similar tribunal for Rwanda were ad hoc criminal procedures that led to the formation of the now-permanent International Criminal Court.

Truth commissions (official, temporary bodies established to document specified human rights abuses, name perpetrators and victims, and identify both the underlying causes and consequences of such violations) have been used in dozens of countries, including Canada, the Philippines, Morocco, and South Korea.

Material and symbolic reparations have been offered in Malawi, Brazil, and Haiti. In Malawi, for example, the National Compensation Tribunal processed claims for monetary compensation to victims of wrongdoing such as wrongful imprisonment and exile during the autocratic regime from 1961 to 1993. Post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe pursued lustration (or “cleansing”), a process of vetting officials for ties to extremist organizations. In Poland, lustration limited the participation of former communist secret police informants from positions in the successor government and civil service. All are part of transitional justice processes.

By addressing and redressing wrongdoing, transitional justice seeks justice for victims and the transformation of political relationships. To transform relationships is to fundamentally alter how members of a political community interact both with each other and with government officials. Transformation is needed when wrongdoing is widespread, with state officials complicit in (and in some cases perpetrators of) wrongdoing. Widespread wrongdoing characteristically occurs with impunity, which is a product of weak state institutions, the absence of political will to hold perpetrators to account, and/or distrust of state institutions, which renders them ineffective. Background inequality often results in members of marginalized communities being more vulnerable to wrongdoing, as their rights claims are less recognized and protected.

These features are present in the American context, as police abuse disproportionately targeting Black, brown, and Indigenous people occurs without meaningful accountability and against a background of racialized inequality.

The five pillars of transitional justice

BECAUSE IT IS concerned with the repair of damaged relationships, transitional justice is linked with reconciliation, a fundamental concept for many faith communities. But the reconciliation pursued in political contexts is not identical to theological understandings of what reconciliation entails. Importantly, forgiveness is not a necessary part of the process of repair and transformation that transitional processes pursue. Nor is forgiveness a goal that such processes should aim to facilitate.

Calls to forgive—understood as the forswearing of resentment and anger stemming toward one’s wrongdoer—make sense against a background of a valuable and morally defensible relationship. In such relationships, a refusal to forgive can obstruct the possibility of maintaining a relationship and reflect an individual’s failure to recognize his or her own fallibility.

However, when the relationship in question is abusive, forgiveness is less compelling. Urging a victim of domestic violence to forgive, for example, does not address the abusive structure of the interaction, can reflect a failure to take seriously the claims of victims to better treatment, and can implicitly encourage a victim to capitulate to her own abuse.

Transitional justice is pursued where political relationships are abusive. Urging forgiveness in response to widespread wrongdoing can reflect a failure to take seriously the claims of victims and their experiences and may implicitly be asking victims to become complicit in their own oppression. Forgiveness by victims will not address the underlying social and institutional conditions that made widespread human rights abuses possible. Yet it is precisely those conditions, and the broader structure of political interaction, that are the root problem and must change.

The repair and transformation that transitional justice requires is built on five pillars: truth, justice, reparations, nonrecurrence, and memorialization. Importantly, transitional justice requires the pursuit of all five together. For example, truth is no substitute for justice. Reparation will not by itself ensure conditions for nonrecurrence.

TRUTH: Documenting and acknowledging the occurrence of human rights violations, their consequences for victims, responsibility for them, and conditions that facilitated their occurrence is necessary. There is a basic right to such truth, and this information provides the foundation for understanding what must change to prevent wrongdoing in the future.

JUSTICE: Holding perpetrators to account for wrongdoing matters for its own sake and contributes to institutional reform efforts by underscoring that no individual is above the law. Respect for human rights is binding on all members.

REPARATION: The harm victims experienced has a moral claim to repair. The sources of harm are multiple: not only the material and physical losses suffered, but also the harm stemming from the denial of the respectful treatment that victims merit. Through redress, communities acknowledge that victims are members of the political community and rights holders.

NONRECURRENCE: It’s essential to alter the underlying social and institutional conditions that explain how wrongdoing became widespread. One common condition is the absence of the rule of law due to corruption or politicization of the judiciary and impunity for abuses by police or security agents.

MEMORIALIZATION: This “fifth pillar of transitional justice” requires communities to commit to remembering the past, including past atrocities, as part of a broader effort to honor victims, understand wrongdoing, and prevent the recurrence of wrongdoing. Memorialization efforts contribute to democratic societies by providing a framework for debating the specific causes of, responsibility for, and present-day effects of the wrongs that are remembered.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, left, chaired the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission and presented its report to President Nelson Mandela.

‘In silence, wounds deepen’

TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE PROCESSES are not entirely foreign to the United States. There are past and ongoing efforts on which the U.S. Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation could build.

For instance, the 1981 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians was a national effort that focused on reparations for Japanese American relocation and incarceration during World War II. The Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Maine and the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission are examples of state-level efforts. At the city level, the Greensboro (N.C.) Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigated “the context, causes, sequence, and consequence” of the events surrounding Klan-related killings on Nov. 3, 1979.

While every country’s experience is unique, there are invaluable insights to be gained from the experiences of other countries and regions. Heeding those insights requires overcoming a common form of American exceptionalism that holds up the United States as only a model for others, and not the other way around.

Comparative experiences from other countries provide lessons of the importance of both local and national truth-seeking efforts. They underscore the importance of calibrating expectations appropriately for what any single truth commission or reparations program can achieve. Transformation does not occur overnight; it is a generational undertaking. Another key insight is that, given the ways religion and racial injustice are interwoven in the United States, churches and faith communities should be part of the process of transitional justice.

Whether looking at dictatorships in South America, genocide in Rwanda, apartheid in South Africa, or the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the story of religion and its place in conflict, repression, and genocide is complex: It’s a story of religious actors who are implicated in, resistant to, victims of, and also perpetrators of political injustice. The Troubles in Northern Ireland fueled conflict between ethno-national communities aligned along religious lines (Catholic and Protestant). Catholic nuns and priests were implicated in the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsis. Catholic Archbishop Óscar Romero was assassinated by government operatives while saying Mass because of his commitment to documenting human rights abuses and speaking against violence during the civil war in El Salvador.

Religious leaders also lead and animate transitional justice efforts. Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu was chair of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In Guatemala, Bishop Juan Gerardi formed a truth commission, while in East Timor Catholic Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo played a central role in calls for reconciliation.

Transitional justice is also useful as a lens for critically evaluating the complicity of religion in upholding racial injustice in the United States. The South African truth process provides a model for the form such critical evaluation might take. While most truth commissions have not focused specifically on the complicity of faith communities in in justice, the South Africa Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) did. As part of its process, the TRC held special hearings on the role of faith communities (ranging from African Traditional Religion to numerous strands of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Baha’i) in both supporting and resisting apartheid.

Faith communities were asked to categorize themselves as “agents,” “victims,” and/or “opponents” of apartheid in their submissions to the TRC. Agents of apartheid reflected on how “the system of apartheid was regarded as stemming from the mission” of the church and how churches “gave the apartheid state tacit support, regarding it as a guarantor of Christian civilization” or, in the case of the Dutch Reformed Church, as required by the Bible, as prominent South African human rights leader Glenda Wildschut reports. They acknowledged the legitimizing role that church chaplains ministering to the South African Defense Forces played through their presence, and the ways in which white churches benefitted from apartheid, able to buy confiscated lands and buildings from Black congregations at reduced prices.

Other faith communities, including the South African Council of Churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples contested, resisted, and suffered under apartheid, according to the final South Africa truth commission report. Black South African religious communities who were victims of apartheid lost land through state confiscations, were forced to sell land at low prices under the Group Areas Act, and had religious activities disrupted, religious buildings bombed, and their leaders targeted for detention, phone tapping, torture, and in some cases murder.

In addition to being partners to and supporters of transitional justice processes that take up human rights abuses committed by state actors or with state complicity, the South Africa example indicates the vital importance of churches being open to interrogating their own roles, as agents or victims of injustice. Publicly documenting and officially acknowledging these roles can provide the foundation for churches to be partners in the broader pursuit of relational transformation in American society.

To be sure, the role of religion in American racial injustice is not entirely unknown. But knowing is not the same as formally and officially acknowledging. Part of what transitional justice does is counter the denial that enables silence about the past to persist and that undermines efforts to redress past and ongoing wrongs.

The centenary this past May of the 1921 white mob’s attack on the Greenwood district of Tulsa helps us remember Christian complicity. First Baptist Church in Tulsa has a prayer room set aside to “provide a place for our church and our community to explore the history of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 and to prayerfully oppose the sin of racism in our world, in our churches, and in our heart.” President Biden noted in his commemoration of the Tulsa attack, “Just because history is silent, it does not mean that it did not take place.”

Biden continued, “We can’t just choose what we want to know, and not what we should know. I come here to help fill the silence, because in silence wounds deepen.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!