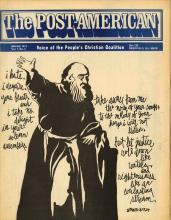

Prophecy is not primarily clairvoyance. In Judeo-Christian history the prophet was God's instrument to check the corruption and oppression which usually attend political power, and to call the ruler to faithfulness to Yahweh and obedience to the divine standard. From the beginning of the theocracy the prophets daringly challenged the king: Nathan condemned David's adultery; Ahijah conspired against Solomon; Elijah vituperated against Ahab's economic excesses and murder; Amos was indicted by the Royal Committee on Un-Hebrew Activities for calling the Daughters of the Samarian Revolution "fat cows" because they were "oppressing the needy and crushing the poor"; Micah denounced the leaders of Israel for "devouring the flesh of the people." Even in the exile, when pious Jews gained the audience of the rulers they confronted them with their injustice (for example, when Esther acted ethically, Haman hung highly). Daniel and his three Hebrew comrades committed four acts of civil disobedience, confronted the government at least five times, and sent one king out to graze with other wild animals, John the Baptist prophesied against the immorality of Herod the Tetrarch. Jesus taught in the temple without permission, drove out those who made capital use of the sacrifices, called a ruler a "fox" (then a nasty epigram), and was executed as a revolutionary.

With the creation of the church, the prophetic mission took corporate as well as personal forms. These early communities were prophetic by their very existence and they resisted rulers who would silence them.

Read the Full Article