In the Mennonite church we hear a consistent call to push pacifism beyond the bounds of refusal of military service. Pacifism, we are told, is more robust than simply refusing to fight in a war. Pacifism is a nonviolent form of life that includes anti-racism, putting ourselves in places of danger to support local peacemakers, and repenting of our participation in systemic economic and environmental violence.

I’m grateful for this stretching, and at the same time I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that Mennonites, alongside other historic peace churches, are a witness to a reign of God that refuses participation in the military. It’s still one of the most difficult and challenging aspects of peace churches as we live out our faith in a militarized world. When new people come to our Mennonite church in North Carolina, whether from other traditions or from no church background, I imagine they are stirred by our views on peace and violence. The strangest part of our religious life is not that we believe that dead people come back to life, or that we try to live like a peasant we believe was God — it is our disposition toward military service.

Anabaptist means “re-baptizer.” It was the name given to our spiritual ancestors, a slur meant to paint them as heretics. The first people to baptize believers upon confession of faith did so because they read the Bible and saw a pattern: People heard the good news of repentance and were baptized. In the 16th century the Roman Catholic Church was both church and state. Baptism records were also citizenship records, used to assess taxation. To be baptized into the church was to become a citizen of the state. And both baptism and citizenship were compulsory within the state-church. Believer baptism called the question of one’s allegiance to the state. The state maintained itself through the military. Calling upon the life of Jesus, the early confessions of Anabaptism describe a kingdom of God in which no sword is drawn, even against one’s enemy. For this radical call to peace, thousands from the movement we now call Anabaptism were burned at the stake or drowned in German and Dutch rivers.

Mennonite refusal to work within the state military apparatus continued in unpopularity into the 20th century in the United States. During World War I, no conscientious objector status or alternative service was available to members of peace churches. Instead Mennonites who refused to fight were thrown into prisons. In Leavenworth prison in Kansas, those who refused to serve in the military were tortured and killed. One mother was sent the bodies of her sons, tortured to death, in plain pine boxes. When she opened the lid she discovered her Mennonite sons had been dressed in full military uniform .

In the Gospels the decision to live within the coercion of state violence, the rejection of self-giving love — this is a kind of hell on earth. This is a story mapped on to history. Roman soldiers of the first century believed they were part of a force that could control the world. But to believe this lie to coerce others, to commit violence against another person — this is a disfiguring of our humanness. It is a fracturing of our souls to carry out the atrocities soldiers carry out in the book of Matthew, from the slaughter of Bethlehem’s babies to the crucifixion of the innocent Jesus.

Peace churches have proclaimed that participation in the military, regardless of the role we play within it, embeds us into a form of power that shapes the world through coercion. In other words, it’s bad for people — both those who suffer under military power and those who keep its machinery intact.

Because I was preaching Matthew’s resurrection narrative, I read a lot about soldiering the week leading up to Easter. I thought about the soldiers in Matthew’s gospel who became “like corpses” at the tomb of Jesus. After the soldiers wake up, they’re bribed, payed large sums of money to keep quiet. If anyone asks, they are to preserve the old order with this story: The disciples came at night and stole his body.

But what we don’t see, what the gospel doesn’t record, is that their lives continue on. I’ve thought about these guards returning home to their old routines. I’ve thought about them lying awake at night — about what it is like to receive the order to suppress a truth you have seen with your own eyes. What was it like to keep information of the resurrection hidden because it would be dangerous to the powers that you keep intact?

A few years ago, I was introduced to a new term: moral injury, defined as “the damage done to one’s conscience or moral compass when that person perpetrates, witnesses or fails to prevent acts that transgress their own moral and ethical values and codes of conduct.” This is how Veteran’s Affairs hospitals talk about those who believe they are giving their lives to service and end up facing terrible moral choices, decisions to obey commands of which they cannot make moral sense.

Surely the soldiers at the tomb suffered moral injury from the command to lie — from the commands to coerce order from people. In the newly ordered dawn of Jesus’ resurrection, the good news reorients how we treat and see the morally injured — those wounded by the state and left to figure out life on their own. We see a catastrophe for veterans of wars in our country in the denial of mental health benefits, the ungodly wait times to receive care, the neglect of hospitals like Walter Reed, the rates of homelessness, and the skyrocketing epidemic of veteran suicide.

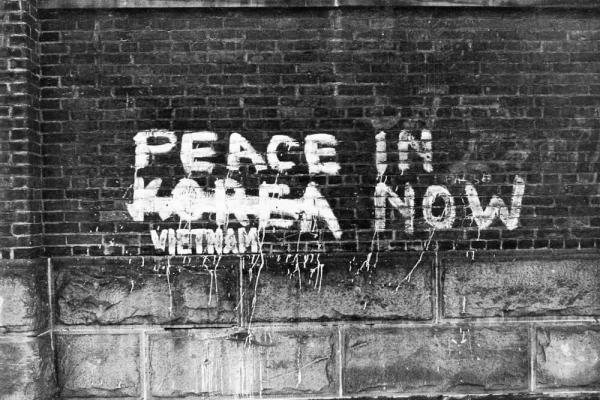

During the Vietnam War, Quakers in North Carolina were part of protest movements, holding candlelight vigils on street corners as a light for the resistance of peace. Chuck Fager, a member of that meeting, saw the results of war included mental illness, homelessness, and despair from those who returned from Vietnam. Often, these veterans were abandoned by the state they gave their lives to protect. And so Chuck planted Quaker House, a mission of the Chapel Hill Friends Meeting. The mission of Quaker House came to be that of a world reoriented toward love, standing in a gap for veterans and soldiers of Fort Bragg.

One of those veterans was Staff Sergeant Josh Eisenhauer. In 2012 he returned from a second deployment to Afghanistan. He brought home a severe case of post-traumatic stress disorder. One morning he started a fire in his apartment. When first responders arrived he began shooting at the door. Eisenhauer was shot several times with return fire from the police. On his way into the hospital he told a nurse he thought he was on a rooftop in Afghanistan, a flashback to a time of exchanging fire with the enemy.

Eisenhauer was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

In prison his mental health collapsed further. It was Quaker House that organized vigils, brought Eisenhauer’s case to state lawmakers, worked tirelessly to get him released from prison and into a mental health facility. Lynn Newsom, now the outgoing director of Quaker House, recently told a reporter at WUNC about a public vigil Quaker House organized. “I was especially gratified that at the vigil, there were people from all walks of life,” she said. “There were the old peace activists shoulder to shoulder with Vietnam veterans, VA workers, the NAACP, bikers that support prisoners of war, just a really broad spectrum, all to support our incarcerated veterans.”

When I think of Easter morning, when I think of the soldiers in Matthew “like corpses,” a sign of the old order toppling, of the law of being loved becoming the new reality, my mind goes to Lynn and the people of Quaker House. Resurrection will put us into a different relationship with the world, one that changes what we see when we encounter it. For some it looks like the end of everything they know. But the truth of Easter is that this is good news for all, that in Jesus, God redeems creation, and us within it.

It’s easy to be dismissive of the peace church witness as overly simplistic. After all, aren’t we all bound up in systems of state coercion and violence? And yet I am thankful that, generation to generation, a people have stood as a witness to the trauma of war, to the trouble of state-coercion, to the power of nonviolent love to transform our world. It is because our churches, rooted to the life of Jesus who loved his enemies even when they murdered him, that we have come to see the good news of peace is the longing of all people.

Together, peace churches share the good news to a world in the grip of violence, to those who perpetrate violence and those who receive the brunt of its deadly force. Both are victims of the last sputtering gasps of the power of this age.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!