Melissa Florer-Bixler is the pastor of Raleigh Mennonite Church and the author of How To Have An Enemy: Righteous Anger and the Work of Peace (Herald Press 2021).

Posts By This Author

‘Women Talking’ Traces Web of Faith, Forgiveness, and Rage

Like the author Miriam Toews, I remember when I heard the news about the “ghost rapes” in Bolivia. I was in seminary training to be a Mennonite pastor. Toews, an ethnic Mennonite who fled her closed community decades before, was living in Toronto. But we shared a visceral and knowing horror as we learned of the events that unfolded in the Bolivian Manitoba Community, events that later inspired Toews’ 2018 novel, Women Talking, and a recent film by the same name.

Judge Jackson Knows ‘We Are Not the Worst Thing We’ve Done’

Hawley's accusation that Jackson is soft on crime reveals a troubling perspective on people who enact harm. Hawley is one of several Republican senators who sorts the world into two types of people: People who are evil and, if given the chance, will commit horrific, reprehensible crimes over and over again, and people like the rest of us, people who need to be protected from the evil people. According to this line of thinking, ensuring this protection shouldn’t rule out the harshest measures of isolation and punishment the state can enact. We separate “them” from “us” by forever marking them as dangerous.

Why My Church Isn’t Dropping Our Online Service

When I asked members of our worship commission what they thought the future of hybrid church might be for us, Rosene wisely reminded us that there are many aging people in our congregation. Before we didn’t have the capacity or technology to continue to include these older adults and disabled people in our regular Sunday worship. What a gift that now we could!

Why Pastors Are Joining the Great Resignation

The Great Resignation is underway in the United States with an astounding 3 percent of employees collectively refusing the terms of low-wages, absent benefits, and dangerous working conditions expected by their bosses. Pastors, too, are walking away. Recent poll data collected by Barna Group, a California-based research firm that studies faith and culture, confirmed what I’m seeing among my friends and colleagues. According to Barna, about 38 percent of Protestant senior pastors surveyed have considered leaving ministry over the past year. Among pastors under age 45, that number rose to 46 percent.

As a Pastor, I Can’t Define Life’s Edges. Neither Can Lawmakers

As a pastor I don’t ask, in this holy space of in between, when death is drawing near, theological questions about personhood or ensoulment. Neither do medical definitions of what marks life’s margins — heartbeats, breath, or brain function — occupy my concern. These are the gray edges of life.

Isaiah Spoke To Vulnerable People, Not Military Superpowers

If the United States is to take up any metaphoric role in this period of Israel’s history represented in Isaiah 6, we are the Assyrians, content to blast our way into any country we like, leaving wreckage and destruction in our wake. Like the Assyrians, my country shows no concern for how its vengeance turns the lives of ordinary people to ash.

Go Tell It on Chapel Hill

For the board of trustees at UNC-Chapel Hill, Hannah-Jones is a living memorial, a journalist who will tell us what happened, who holds up memory and urges us not to look away.

'No One Will Take Responsibility for Faye Brown's Death'

Faye Brown was 23 when she went to prison. This week a coroner will report that Brown died at a local hospital of complications from the coronavirus at the age of 67.

Why We Held Bible Studies at the Base of Confederate Monuments

EVERY DAY, BEFORE the coronavirus had us sheltering in place, I drove by a Confederate monument on the state capitol grounds near my home in Raleigh, N.C. It was unveiled in 1895 by the granddaughter of Stonewall Jackson, Julia Jackson Christian. Its 75-foot-tall granite column is a fixture of the landscape as people walk past on their way to work or sit on benches beneath its shadow, the shaft marked with the words “to our Confederate dead.”

The monument is strategically placed to assure maximum visibility. Everything about it is purposeful and planned. It makes a claim on the space—claiming the ground, the air, the power of public land with a particular version of history.

“To our confederate dead.” But the question that burns on the stone: Who does “our” represent?

Injustice, idolatry, and repentance

IN 2019, CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va., was still reeling from the August 2017 Unite the Right weekend during which counterprotester Heather Heyer was killed by a white nationalist. Two local Methodist pastors—Rev. Isaac Collins and Rev. Phil Woodson—decided to gather community members for a weekly Bible study aimed at reinterpreting the Confederate monuments that mark Charlottesville’s public space. They called it “Swords into Plowshares: What the Bible says about injustice, idolatry, and repentance.”

The inspiration came from Jalane Schmidt, a public historian and religious studies professor at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, who has co-led truth-telling tours of the monuments since 2018. Schmidt suggested Collins take up the work of theological interrogation of the history embedded in these monuments and how this history lives on in the churches and Christians in their city.

I Refuse to Participate in Worship that Leads to Devastation

I suspect Trump thought I, a pastor, would be overjoyed by this news. After all, Easter is the most sacred day of the Christian year. It is the day we celebrate life over death and hope over fear. The thought of watching my congregation gather on Zoom for this holiest of days has left me sad and discouraged. I’ve silently mourned each week that my congregation cannot sing together, or share meals or hugs. Instead, we click a link to see each other’s faces appears in the grid of a computer monitor.

Don't Compare Impeachment with the Racial Terror of Lynching

It's impossible to use the language of lynching without calling to mind horrors like those visited upon George Taylor.

The Forgotten Christian Discipline of Loving Your Enemies

I have never met Robert Alfieri, but he is my enemy.

Alfieri is acting assistant field office director for Immigration and Customs Enforcement in my part of North Carolina. For Alfieri, it’s a job. He believes he keeps people like me safe from violent criminals. But in the time that Alfieri has overseen ICE in our area, hundreds of people, mostly Latinx community members, have been disappeared at traffic stops and picked up during raids at their workplaces. At our local elementary school, children wait in administrators’ offices for a parent who will never show up. Birthday parties and baptisms are tinged with anxiety and sadness as communities contemplate the forced separation from those they love. Families scramble to make ends meet when a primary breadwinner is kidnapped at work.

In a recent round of ICE raids in Durham, a young father was picked up while packing his car for work, collateral damage among the targets set by ICE. In a nearby NICU his premature infant—born at seven months—waited alone. Maria, the baby’s mother, recovered from surgery while her spouse sat in a detention center, hoping our community could raise the $15,000 bond set by a judge. Eventually they raised $7,000, securing the rest through a loan. ICE officials “don’t have a heart,” Maria told a local reporter.

This young father, the main wage earner for his family, was in ICE detention for many reasons, including xenophobic immigration policies, decades of U.S. interventionist politics in Central America, the mythic war on drugs, and the complicity of the American public in fictive safe-keeping from their undocumented neighbors. But he was also in ICE detention, separated from his family, because of Robert Alfieri.

An unsung discipline

When someone shares with me that they have an enemy, it is often in pastoral confidence, whispered as a confession. Having an enemy, they intuit, is a botched form of discipleship resulting from failed reconciliation. The language of enemies is seen as the end of a conversation—or the end of relationship.

When Your Sexual Harassers Sit in Your Pews

When I heard that Rev. Butler was appointed the first woman pastor of Riverside, I thought she broke the stained-glass ceiling. Instead, the church threw her off the stained-glass cliff. The phenomenon of the glass cliff is one documented throughout the working world. Women are invited into senior-level leadership only at times of crisis, when intractable problems, often caused by male predecessors, cannot be solved. There’s nothing to lose because things have hit rock bottom.

The Cost of Nonviolent Faith in a Hyper-Militarized World

When new people come to our Mennonite church in North Carolina, whether from other traditions or from no church background, I imagine they are stirred by our views on peace and violence. The strangest part of our religious life is not that we believe that dead people come back to life, or that we try to live like a peasant we believe was God — it is our disposition toward military service.

The Kin-dom of Christ

Lamps and debt. A friend in the night, and a sower of seeds. Wine, nets, pearls, weeds, and treasure. What is the kingdom of God like? It is like leaven and it is like two sons, like bridesmaids and sheep, like workers and judges.

In the 37 times that Jesus describes the reign of God in the Gospels, not once is the kingdom of God like a kingdom of earth. Thirty-seven times Jesus reshapes the imaginations of his followers. Thirty-seven times Jesus tells them a story to help them remake the only world they know.

A Resistance Playlist for These Days

The work of liberation is long and hard, but music is one way we are sustained and renewed. I asked women in the throes of decolonization, activism, community organizing, pastoring, and liberative writing what songs encourage them as they engage in the work of justice and resistance. Here are their responses.

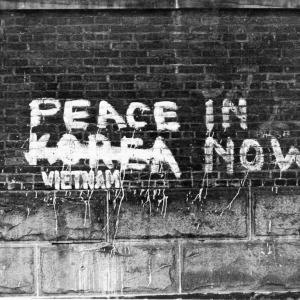

Peace Not Reconciliation

In the face of these questions I am thankful for the ways in which Nehemiah complicates our ideas about forgiveness. He reminds us that forgiveness can be a difficult and life-changing road. What we find is that forgiveness doesn’t nullify the consequences of sin. Neither is forgiveness synonymous with reconciliation… We can forgive another person and even, in a sense, be at peace with them without a full restoration of the relationship.