During the pandemic, something peculiar happened: The child poverty rate in the U.S. fell, reaching an historic low of 5.2 percent in 2021. The decline was largely a result of the federal spending in social safety nets like Medicaid, SNAP, and the Child Tax Credit, as well as direct payments to families. Anti-poverty advocates celebrated the win.

“Policy works when you make good policy,” said Todd Post, senior domestic policy advisor with Bread for the World, a Christian anti-hunger group. He attributed the dramatic decline in child poverty directly to the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. “I think it was the most important anti-poverty program in 50-60 years.”

Anti-poverty advocates are used to playing the long game, Post said, but the 2021 expansion felt like it “dropped out of heaven.” Then, in 2022, Post said, it vanished just as quickly, and the consequences were immediate.

In 2022 the Child Tax Credit returned to pre-pandemic rules, and newly released Census data shows that the percentage of children living in poverty more than doubled from 2021, rising to 12.4 percent — almost 9 million children. In total, 15.3 million Americans reported incomes below the poverty line , which is around $30,000 for a family of two adults and two children.

“The expanded CTC illustrated the power of a fair tax code by driving historic reductions in child poverty and food insecurity,” said Children’s Defense Fund president and CEO Rev. Starsky Wilson in a news release . The children’s welfare nonprofit attributed the spike in poverty directly to the expiration of the CTC expansion, along with persisting hardships for families with children, especially Black and brown families.

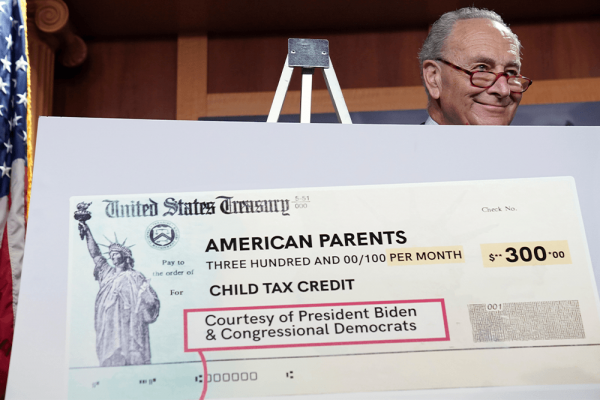

The 2021 CTC raised the maximum payment from $2,000 to $3,600 per child and changed a refundability rule that had kept the lowest income families from qualifying for the full amount. It allowed for half the credit to be paid in advance monthly payments, and raised the oldest qualifying age from 16 to 17 years old. Restoring full refundability would allow families with minimal or no income — families that need the relief the most — to receive the full credit. Under the current rules, a family is not entitled to the full credit until their tax liability exceeds the amount of the credit.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive research institute, analyzed census data and found that expanding the $2,000 Child Tax Credit for lowest income families would cost around $12 billion per year and reduce “the number of children living in a family with income below the poverty line by roughly 16 percent — or about 1.7 million children.”

Even though getting the full expansion back would be ideal, advocates say, restoring parts of the expansion would help families.

“Even a more modest compromise expansion this year focused on children with low incomes could have a significant impact and partially reverse the stunning spike in child poverty the nation saw in 2022,” said CBPP president Sharon Parrott in a news release. “Expanding the Child Tax Credit should be the top tax policy priority for lawmakers this year and during the 2025 tax debate.”

In addition to more families receiving full credits, the 2021 rules allowed the refund to be paid in advance monthly installments. These kind of direct cash transfers make the biggest impact on hunger, specifically, Post said, because families don’t shop for groceries all at once at the end of the year when their tax refund check comes in. “Fighting hunger is all about cash flow.”

Bread for the World tracked measures related to child hunger and found that during the months of the direct payments in the second half of 2021, data was showing promise. Their findings were in keeping with other direct cash transfer pilot programs, also known as universal basic income, which pays families a monthly stipend of unrestricted cash.

“We have the evidence,” Post said, that direct transfers go toward family needs. The same was true for the CTC.

Taking note from the success of the emergency measures, Congress could consider other options to prioritize working families, Rachel Anderson, a fellow and strategic advisor at the Center for Public Justice, a Christian policy think tank told Sojourners. A holistic approach would also include things like paid family leave.

“Families are the starting point of a healthy society. When they flourish, our whole society flourishes," she said.

Without swift action from Congress, other measures of family well being are actually likely to get worse, according to Parrott’s statement, which pointed out that in the 2022 Census data, health care coverage was still strong. A record low 7.9 percent of Americans were uninsured, largely thanks to a pandemic rule that prevented people from being expunged from Medicaid rolls. Since that provision expired in the spring, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that 6 million people have lost coverage, meaning that next year’s Census data will likely show that those gains have also been erased.

All of this amounts to more strain on more families, with children inevitably bearing the brunt of the gaps in social programs, advocates say.

The emergency measures showed how much more pro-family programs could be doing to ease the strain on working families even outside the pandemic, said Anderson.

“The child tax credit is one way policy-makers have supported the vital but very intense work that families do,” she said. “A recent boost to the child tax credit came about in the midst of the pandemic but, in reality, simply brought the program closer into line with the ongoing needs of families.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!