This interview is part of The Reconstruct, a weekly newsletter from Sojourners. In a world where so much needs to change, Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair. Subscribe here.

The Reconstruct will be taking a week off on Tuesday, Nov. 5 as we will be primarily focused on the election.

You might think that the people who most fundamentally believe in humanity’s fallen, sinful nature — Calvinists — would also be the most reticent to concentrate power in a small sect of humans.

But often, as Kristin Kobes Du Mez told me in our interview, Calvinists are one of the Christian groups on the front lines of movements where power is concentrated in singular leaders, singular expressions of Christianity, or singular heads-of-households. Kobes Du Mez, a historian at Calvin University, finds this baffling, but can’t deny that the movements are linked. As she sees it, Christian patriarchy, Christian nationalism, and anti-democracy movements are connected by their approach to power.

In a new documentary short, For Our Daughters, Kobes Du Mez and director Carl Byker address the connection of these movements through the stories of sexual abuse victim-advocates: Rachael Denhollander, Cait West, Christa Brown, and others tell the stories of how sexual abuse was allowed, ignored, or covered-up in their communities while analyzing what Christianity has to say about it.

As the gut-wrenching stories are told, the film keeps its focus squarely on the question of power: Who wields it, why are Christian men willing to protect their power at all costs, and who does that harm? The film then takes another turn to ask: Where does this abuse of power seep into our political lives? How does abuse of power in the small communities of churches align with the abuses of power in our larger communities of cities, states, and nations?

In our interview, Kobes Du Mez explained the origins of the documentary, her work on Christian arguments for democracy, and the power of victim-advocate stories.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mitchell Atencio, Sojourners: What was the timeline and process for making this documentary?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez: I was approached by the director, Carl Byker, maybe a couple of years ago with interest in doing a project related to Jesus and John Wayne.

So, we started talking and playing around with different ideas. If you know anything about the documentary film world, nothing is a straight line. [You’re] conceiving of multiple different projects, testing things out. The footage that went into For Our Daughters was initially just [starting] with some of these women’s voices, based on the last chapter of Jesus and John Wayne.

Doing initial interviews — they were so powerful. For somebody like me, I know these stories, I’ve been in this space for years now, I’ve been following these stories for more than a decade. Still, it was startling to hear them expressed in this fashion and to hear the women themselves. [They] explain what happened with such clarity and with such power.

I’ve been watching these survivor spaces. I’ve been watching all the attempts to discredit and smear survivors and advocates. But it was actually Carl, the director, and other members of the film team who were absolutely blown away, not having heard these stories and not having been familiar with them.

So, we were sitting there, and Carl said, “We need to do something with this.” And there’s a long timeline for a larger project. But he really was convicted that these voices needed to have a wider hearing in this moment.

Long answer to a short question, but [ For Our Daughters] wasn’t what we’re going to do. It was the women’s stories that told us we need to do this.

I’m wondering about the timing of the election being around the corner. It seemed like the timing was consciously tied to the political arena. Is that right?

Yeah, absolutely. If you read Jesus and John Wayne, I came to the story of abuse inside evangelical spaces by writing a broader history of politics and gender. [Specifically] of evangelical masculinity as linked with militarism and a militant Christian nationalism.

I make the case in the book that the common thread here is a conception of power and Christianity. Power that is power over others. Power that is about hierarchy, authority, and submission. And a coercive power.

I link this Christian nationalist quest for power and ends-justifies-the-means mentality with abuse of women inside these spaces. And the coverups of that abuse. Consistently [we see] this pattern over and over again.

Yes, there’s a political framing to the project that inspired this. Because of that, we thought it was important to release in this moment, both for Christian women, for women who find themselves in these spaces, and for all American women.

It’s these women who can say, “We’ve lived inside these communities that are structured by this kind of power, and we bear the scars.” And right now, many of the Christian nationalist pastors who are taking a leading role in articulating the Christian nationalist framework and infusing — not just sectors of the Republican Party, but if you read a document like Project 2025, you can draw direct links between contributors to that project and the men who are spouting patriarchal teachings and implicated in abuse scandals.

Growing up, many in my community naively thought that sex abuse scandals were just a Catholic thing or a celibacy thing. And then when the Southern Baptist abuse scandal broke, some said it was a complementarian and conservative issue.

For readers who don’t think of themselves as Christian nationalist or complementarian or think that abuse scandals aren’t happening in their camp, what can they take away from the documentary?

Just because you’re not hearing stories doesn’t mean there aren’t stories to be heard. As soon as you start speaking on this issue and writing on this issue for several years [as I have], you will start hearing stories.

In this film, because we are looking at evangelical spaces, we can see that a particular theology of authority and submission is operative in terms of how the women are treated, but also how they respond.

Many didn’t even have the capacity to [immediately] identify what happened to them as abuse. Theology runs through and through here, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t twisted theologies at work in mainline or progressive spaces. And certainly, I think you would encounter the same temptations from church members to cover things up.

If allegations surface, the overwhelming desire to protect the “witness of the church,” to protect the man’s ministry, these things do extend beyond conservative evangelical spaces. Inside conservative evangelical spaces, maybe we can say there’s a perfect storm here. But I certainly wouldn’t want to suggest that this problem is unique to those spaces.

It is, however, a profound problem inside evangelical spaces and linked to this Christian nationalist vision, which ups the stakes for everything [in their minds]. If Christianity is “under attack,” if Christians are “under siege,” if the ends will always justify the means, then you have to [protect] that bond aggressively. You have to defeat them before they defeat you.

That kind of rhetoric absolutely exacerbates the situation inside conservative circles. But again, I think you’d want to look closely and not give a pass to dynamics inside more progressive spaces. They would look a little different. I think there’s a higher likelihood of people inside those spaces having an awareness around issues like abuse and best practices — contact law enforcement and things like that.

In conservative evangelical spaces, for decades, they’ve really worked to reject those perspectives and to insulate people inside their communities from these broader discourses around abuse and women’s rights.

What does your research say about what happens when this goes right? What happens when sex abuse is responded to correctly?

Full disclosure: I’m not trained in the area of abuse response prevention. Obviously, I read some in that area. But I’m a historian and I’m much better at describing what has happened.

I don’t know if I can say more frequently, but in the last couple of years, I’ve encountered a couple of cases where it seems like churches have responded very well. They take allegations seriously and notify law enforcement — for all of its limitations, that brings in outside accountability.

Very few churches are equipped to handle situations like these, which often require some level of investigation. My experience is in higher education — so Title IX and so on. Having served in that capacity, a carefully vetted investigation is really important for all parties.

Simply taking those steps, I have seen a couple of cases where that has been done. Another piece, which is often a really painful piece, is to then go public and use the failures of leadership, the perpetrator, and to genuinely use elder boards and so on to hold pastors accountable — to actually do the work they’re supposed to be doing.

That public step is often what’s missing. There aren’t a lot of successful cases in part because that public step, up until recently, has often been missing. So, it’s hard to know. The cases I [am able] to examine as a historian are just this tiny fraction of abuse scenarios and outcomes inside the church.

Since the film’s release, I’ve been hearing so many stories from women — and men. I just got an email late last night from a man I know saying, “We watched it twice last night because this happened to our granddaughter, and this has helped us understand those dynamics.”

So, taking it seriously, notifying law enforcement so there’s that external accountability, knowing your limitations of what you can deal with internally, and then acting upon it with proper discipline and exposure. While protecting the victim and their family and providing support. It can happen. Those cases don’t make the news as often.

That said, I always hold my breath. Because sometimes it seems like a case has been handled well, but even that is [public relations].

And [later we learn] it was actually much deeper. I don’t want to be a cynic at all. I love to hold up good examples, but I’m always cautious. Give it a little time to make sure this holds.

So often, I’ve seen a little bit of exposure, a little apology, a very quick turn to forgiveness and restoration. And you realize the exposure and the confession only scratch the surface. It masked what really happened.

Before I ask you about the connection between sexual abuse and Christian nationalism, do you think of Christian nationalism as a continuation of an old movement or something different and new?

It’s both. Christian nationalism as a term really hit the mainstream media in the weeks and months after Jan. 6, 2021. As a historian who has a book that mentions Christian nationalism, I was blown away.

[I was] brought in on a lot of interviews and literally the first thing I would insist on saying to every journalist was, “This Christian nationalism is nothing new to scholars. We’ve been talking about this for a long time, and we can identify different iterations of it over time and how it changed over time.

This vision of a “Christian nation that reflects God’s laws,” or “true Americans are Christian,” you can find iterations of that going back to the Puritans. You can find it in Manifest Destiny, you can find more progressive iterations in the early 20th century. Progressive Christianity had a certain vision of the “Christian nation.”

Some would even suggest we look at the “beloved community,” in the Civil Rights movement.

And, it is new in that the dominant form of Christian nationalism, when people say, “Yes, America should be a Christian nation today,” — we have a lot of survey data that spells out exactly what they mean by that.

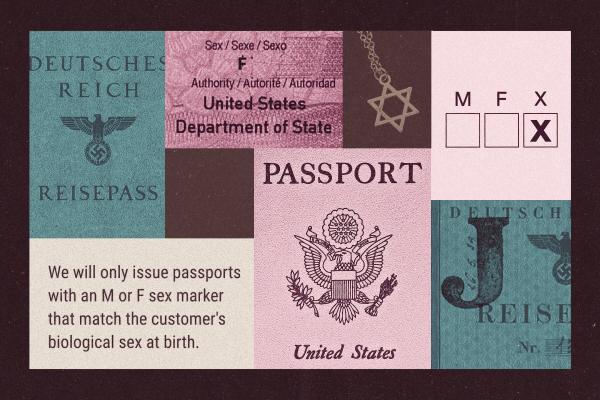

Unlike some of the other versions, [the current movement’s] relationship to democracy is key here. This is not a movement that wants to expand democracy and not a movement that wants to elevate all Americans. This is very much an us-versus-them mentality that wants to restrict access to political power to Christians — and to particular Christians — who share their agenda. And what is that agenda? It aligns closely with the Right-wing of the Republican Party.

I get impatient with people who think it came out of nowhere. It didn’t. But I also get impatient with people who say, “Oh, yeah everybody was a Christian nationalist in American history,” without the specificity of what form that took.

What is unique about today’s Christian nationalism is that relationship to democracy. Christian nationalists, increasingly, are quite open about their abandonment of democracy. Knowing that, because of demographic changes, the numbers are no longer on their side.

We have what Robert P. Jones has called the “end of white Christian America.” Just look at the popular vote in recent elections. It is clear that democracy will not help them achieve their aims. So now we have more explicit anti-democratic, and even authoritarian, leanings within those who espouse this “Christian America” ideal.

As it relates to your film specifically, there’s a desire to decrease democracy for women — to eliminate women’s right to vote — right?

That is not the majority position. But I include that example in my book because I came across it in my research. At first, I had no intention — I thought it was super fringe. “Some of these Christian patriarchy guys are saying that women shouldn’t vote. I can’t include that because I’m going to get accused of centering on the fringe figures, the extremists, and trying to make everybody look bad.” But then I just kept bumping up against it.

When I was looking at the conversation around it, I realized [eliminating women’s suffrage] is the logical outcome of their teachings — of male headship, of a patriarch having full power over his wife and children, of him representing God’s authority. I included it, not as the main story by any stretch, but I included it in Jesus and John Wayne as an example. And I’m seeing that surface with greater frequency now in Christian nationalist spaces.

More broadly speaking, we can absolutely say that there is a tight correlation between Christian nationalism with gender traditionalism and patriarchy.

The first voice in the film, Cait West, her story is that she was growing up in a fairly normal Christian home until her dad came under the influence of Doug Wilson’s teachings [which] pulled them into this Christian patriarchy space, and she was forced to be a stay-at-home-daughter.

Doug Wilson [has had] a prominent role in the Christian patriarchy movement; more recently, he’s taken on a prominent role in advancing this Christian nationalist agenda. He’s a prime example of the intersection of these ideas and the growing power [of those ideas].

Why is democracy part of the antidote to ideas like Christian patriarchy or Christian nationalism?

I was out in D.C. [recently] as part of the unveiling of the Christian Faith and Democracy statement that I worked on for several months as part of a drafting committee. I spent several months really digging into Christian theology and Christian history to make a case for democracy as a Christian and to fellow Christians.

One caveat: Democracy is not the only form of government that Christians have advocated for or will advocate for. As some Christian nationalists like to point out, democracy is indeed not in the Bible.

I make the case that democracy, in our time, is the best mode of government to recognize the image of God in our fellow citizens, to protect one another from abuses of power, and to protect ourselves from becoming abusers of power. And I think that’s really key.

I was a special contributor to one part of the statement, and that was the part about sin. What has always shocked me is how Calvinists and Reformed folks are often those on the front lines of this Christian nationalist movement and are wanting to take over the country for God’s glory; they have a theology that says we are all fallen. And that includes them. It includes those with power. The more power you give people, the more power they have to do evil.

As a Christian, democracy provides us with some very essential, healthy checks and balances against abuses of power. And that’s really important for Christians themselves. Because what’s extremely dangerous is when we, as Christians, lose a sense of humility and a sense of our own fallibility and conflate our desires with God’s will.

I see that happening over and over again in Christian nationalist circles — an utter lack of humility and absolute conviction that they are doing God’s will. Anybody who critiques them is attacking God, and if God and Christianity are at stake and under threat — because apparently God isn’t powerful enough to cut through this — then the ends will always justify the means to protect “Christianity.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!