In a world where so much needs to change, Sojourners’ Mitchell Atencio and Josiah R. Daniels interview people who have faith in a new future and are working toward repair.

This series features interviews with artists, activists, authors, scholars, contemplatives, and others who are willing to name the ways our world and churches are broken — and how we can all work to build a better future.

Subscribe to our newsletter: You'll be the first to know when new interviews are published, plus you'll get bonus material that we won’t publish online.

Photo of Jamelle Bouie. Graphic by Ryan McQuade.

The Constitution isn’t just a symbol, it’s the base document for our democratic republic. And Jamelle Bouie says that in a time of crisis, it's important to remember that in a democracy, we have ownership over its meaning.

Photo of Musa al-Gharbi. Graphic by Ryan McQuade.

The term “woke” has become something of an anathema in recent years. Those on the Right use “woke” to disparage anything they think of as social justice or political correctness. Those on the Left initially deployed the term to describe a person who was socially conscious, but after it became apparent that banks and corporations were adopting “woke” coded language, and that the semantics of “wokeism” were more performative than substantive, “woke” fell out of vogue.

John Hawthorne. Graphic by Ryan McQuade

The culture war and a moral panic around "wokeness" has many in Christian higher education living in fear. Now, one former educator is charting a new path.

Yanan Rahim Navarez Melo. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

Yanan Rahim Navarez Melo is a theologian getting his MDiv at Princeton Theological Serminary. He's also an artist pushing the boundaries of a burgeoning genre known as postclassical music. Here's how he sees these two areas of study overlapping.

Gary Dorrien. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

As a theologian, ethicist, professor, priest, and author, Gary Dorrien has helped shape and excavate the overlap between social justice and faith for nearly 50 years. He has written definitively as a historian and prophetically as an activist, all while teaching generations as a professor of religion. Now, he explains why it was time to tell his own story.

Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

I’d wager that whether you are new to Sojourners or a longtime subscriber, you probably have a deep admiration for the late Salvadoran archbishop and liberation theologian, St. Óscar Romero. And if you don’t, then you’re about to.

Grace “Semler” Baldridge. Photo courtesy Semler. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

As Semler, Grace Baldridge has spent the past few years proving there was a space for people like her in the Contemporary Christian Music scene, even if she had to dig that space with her bare hands. Now, with the release of her debut album, she's looking back on how she did it — and what’s next.

Molly McCully Brown. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

Whatever multitasking, social media doomscroll, or email hell you’ve got yourself in right now, I want you to slow down, take a deep breath, and give your full attention to this interview.

Eliza Griswold. Original photo by Seamus Murphy and courtesy DeChant-Hughes Public Relations. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

In 2019, poet and reporter Eliza Griswold began reporting on Circle of Hope, a church founded in the spirit of a radical evangelicalism that motivated the likes of Tony Campolo, Ron Sider, and Jim Wallis. Her new book, Circle of Hope: A Reckoning with Love, Power, and Justice in an American Church documents her experience.

The church, founded in 1996 by the couple Rod and Gwen White, had spread to four locations by 2019. Griswold saw the flourishing, growing community as an intriguing example of evangelicalism untied from the Religious Right.

Image of Lerone A. Martin. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

A favorite movie of mine growing up was the 1999 cartoon Our Friend, Martin. It combines two of the subjects I love most: time travel and Martin Luther King Jr. The main character, Miles, a Black sixth grader, visits the childhood home of King and ends up traveling back in time to meet King at various stages of his life. Miles, who was largely unaware of King before time traveling, eventually learns that King was assassinated. In order to prevent this, Miles convinces his new friend Martin to come to the future with him. And while that decision spares King’s life, the movie makes it clear that Miles saving his friend’s life would prevent the racial equality we now enjoy in the U.S.

In the modern U.S., are we really enjoying a post-King racial equality?

Aaron Robertson. Photo by Noah Loof, courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

Digging through the basement of the Bishop Payne Library last year, I came across a book titled Black Christian Nationalism.

I laughed, snapped a photo to send it to my friend and co-editor Josiah, and kept on looking for the book I had meant to find. Josiah and I joked about how the book might confound liberal Christians who are overly focused on rooting out “white Christian nationalism” without clearly defining what that phrase actually means, considering whether it's a problem in their own congregations, or listening to good-faith criticisms of their efforts. But I couldn’t stop thinking about the book. Written by Albert B. Cleage, Jr., a pastor from Detroit, it is a provocative proposal that drew from separatist politics and liberation theology in the quest for the freedom of Black people.

Rev. Munther Isaac. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

When I visited Rev. Munther Isaac in Bethlehem, the West Bank, in October, he mentioned that he was previously opposed to liberation theologian James H. Cone. Isaac was trained in theologically conservative teachings, growing up in a conservative church and then leaving Palestine to attend a conservative seminary in the U.S.

Robert Downen. Photo courtesy Downen, graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

What I’ve most appreciated about Downen is that investment in community. To report on abuse in the SBC, Downen had to earn the trust of everyone from powerful, complementarian pastors to radical, queer exvangelicals. His reporting, as we discussed below, is focused on impacts of power and policy instead of being driven by personalities.

In our interview, we discussed how anti-democracy organizing and Christian sex abuse overlap, what reporters need from their communities, and why he treats religious organizations as institutions with power.

A Trump flag flies on a crane on the corner of Spring St. and California St. on the south side of Socorro, New Mexico,on Nov. 16, 2024. REUTERS/Andrew Hay

For a long time, I’ve wondered how, on a practical level, something like mass deportations would work. Specifically, I’ve wondered how churches providing shelter to immigrants will respond if and when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents show up to deport people seeking refuge. What can faith communities, activists, and people of conscience do to tangibly help immigrants right now?

Mason Mennenga. Photo courtesy Mennenga. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

If you’ve encountered Mason Mennenga online, it’s likely due to one of his viral tweets.

Gems like “bible college girls are like ‘marriage is so hard’ yeah, you married a 19-year old evangelical man” and “christians will name their kids after old testament prophets and then are shocked that their kids eventually speak out against injustices.” Occasionally, he dunks on a conservative personality, or he becomes the punching bag for conservative voices frustrated by his progressive theology.

But Mennenga is more than a social media account. He hosts two podcasts, writes about theology and culture, and works as director of admissions at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities.

Andrew Wilkes. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

Back when X was called Twitter, and back when I had social media, I met Andrew Wilkes. I had read some of Wilkes’ writings on Black radicalism and capitalism, and immediately decided he was someone worth following. Not only was he writing on topics that occupied a major preoccupation of my own, but he was also a Black Christian. While I think it is largely a myth that leftist politics is primarily a “white space” (whatever that means), I think it’s fair to say that Black Christian leftists are a rarity. So when I discovered Wilkes, I made a commitment to follow his work.

Robert Monson. Original photo by Joseph Peterson courtesy Robert Monson. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

I’ve followed Robert Monson’s work for years. Monson is a writer and theologian who focuses on Black theology, contemplation, and disability. He is also one of the first people outside my direct orbit to encourage my writing (not just my reporting), and I’ve always found him to be encouraging, joyful, and thoughtful.

Lately, as I have been reading Monson’s work, I’ve found that he is becoming rather soft. Now, before you think those are fighting words, I’ve thought this because it’s the term that Monson uses to describe himself and his aspirations as a man. He sees softness as an ethic to live into, a way of honoring his personhood and the personhood of others.

D. Danyelle Thomas. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

D. Danyelle Thomas, the digital pastor of Unfit Christian and the author of The Day That God Saw Me as Black, also finds theological meaning in fiction. One of the conversation partners for her book is the literature of Toni Morrison. I love Morrison because her characters are often struggling with life’s deepest theological questions while also proudly asserting that they are Black and beautiful. Thomas articulated this idea in her own words, saying, “I don’t navigate this world without my Blackness, so I certainly won’t navigate my relationship with God without it.”

Image of Kristin Kobes Du Mez. Photo credit: Deborah Hoag. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

You might think that the people who most fundamentally believe in humanity’s fallen, sinful nature — Calvinists — would also be the most reticent to concentrate power in a small sect of humans.

But often, as Kristin Kobes Du Mez told me in our interview, Calvinists are one of the Christian groups on the front lines of movements where power is concentrated in singular leaders, singular expressions of Christianity, or singular heads-of-households. Kobes Du Mez, a historian at Calvin University , finds this baffling, but can’t deny that the movements are linked. As she sees it, Christian patriarchy, Christian nationalism, and anti-democracy movements are connected by their approach to power.

In a new documentary short, For Our Daughters, Kobes Du Mez and director Carl Byker address the connection of these movements through the stories of sexual abuse victim-advocates: Rachael Denhollander, Cait West, Christa Brown, and others tell the stories of how sexual abuse was allowed, ignored, or covered-up in their communities while analyzing what Christianity has to say about it.

Titus Kaphar. Courtesy Revolution Ready Films. Photo by Mario Sorrenti.

In the first few moments of Exhibiting Forgiveness, La’Ron (John Earl Jelks) is beaten after he defends a store clerk in a convenience store robbery. The violence, like most of the violence in the film, is just out of view. Soon the scene shifts and Tarrell (André Holland) wakes from a nightmare. His wife Aisha (Andra Day) reassures Tarrell that he is safe in the beautiful world they are building for themselves as artists and parents.

Richard B. Hays and Christopher B. Hays. Original image of Richard courtesy Duke University. Original image of Christopher courtesy Fuller Theological Seminary. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

“Some people out there in the readership are all in a tizzy that ‘Richard Hays has changed his mind! He’s changed sides! He’s not on our team anymore!’ They think this is some kind of a radical reversal. In spite of what he wrote in the first book, [The Widening of God’s Mercy] is consistent with the man that I had grown up with and known my entire life.”

Photo credit: Haley Bateman. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners.

I contain multiple identities. On the one hand, I am a Black man whose ancestors were enslaved, then pushed into ghettos, and now exploited through the unjust prison labor system. On the other hand, I am living on the stolen land of the Duwamish people. I can’t escape the colonial history of the U.S. and its reverberating effects.

There are times when I try to convince myself that, because I am a Black person living in the U.S., it’s not my responsibility to wrestle with the legacy of colonialism and how I might be a beneficiary of that history. However, after my conversation with author and activist Patty Krawec, I am convinced that I need to view myself through a more complicated lens.

Image of Flamy Grant. Photo by Sydney Valiente. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

Flamy Grant called in to her morning interview after participating in a day-long silent retreat. Well, not a silent retreat exactly — it was a vocal rest.

After spending the last year touring the U.S. off the success of her album, Grant, who prefers to use her stage name in interviews, needed to rest her voice. Since her rise to Christian music stardom — or infamy, depending on how one feels about a drag queen topping the Christian charts — she has performed in bars, clubs, and churches spreading the good news in glitter.

Image of Terry J. Stokes. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

In Against Me!’s song “I Was a Teenage Anarchist,” Laura Jane Grace sings, “I was a teenage anarchist / But the politics were too convenient.” The song is a catchy tune that has stuck with me, even if I’ve outgrown the punk-rock-emo scene. But unlike Grace, I have not outgrown my anarchistic impulses.

Popularly, anarchy is associated with “chaos,” but I think of it more in terms of avant-garde jazz, where everyone is working together in their own unique way to create a sort of consensus.

So, when I recently heard of a new book focused entirely on the nexus between anarchism and Christianity, I had to investigate.

Friedel Dausab. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

I was listening to BBC’s Focus on Africa this summer when I first heard Dausab interviewed about his role in the landmark court case to overturn Namibia’s anti-LGBTQ+ legislation. In a throw-away line, the host indicated that Dausab was a Christian — and Dausab didn’t equivocate.

“As a born-again Christian, I always go back to Jesus …,” Dausab told the host.

Who was this born-again Christian that brought down Namibia’s sodomy laws? I wanted to meet this guy.

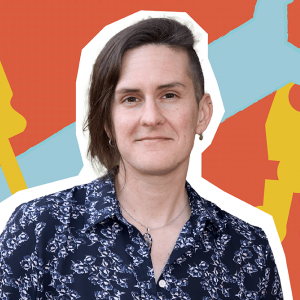

M Jade Kaiser. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

Two queer pastors, Anna Blaedel and M Jade Kaiser, were having dinner together in 2017, when they posed a question to each other in the spirit of meaningful fun: What would it be like if they could create a public space for conversations about and liturgical resources for transformation, at the outer margins of Christianity and beyond?

Abby Olcese. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

In her forthcoming book, Films for All Seasons: Experiencing the Church Year at the Movies, Abby Olcese guides the church through the liturgical season via spiritual reflection on movies. Rather than tell readers how a movie is to be interpreted, Olcese guides participants on watching, considering, and discussing 27 films, each aligned with the liturgical calendar.

Rev. Anastasia E. B. Kidd. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

Travel back in time with me to the early 2000s: Celebrities were openly fat-shamed in tabloids, and supermarkets were overrun by all things “low” — low-calorie, low-fat, low-carb, low-sodium, or low-sugar. Diets like Atkins, paleo, keto, raw foods, and juice cleanses abounded. TV shows like “The Biggest Loser” and “My 600-lb Life” were used to paint fat people as lazy, undisciplined, and disgusting.

Lydia Wylie-Kellermann. Graphic by Ryan McQuade/Sojourners

Over the course of my life, I have been part of political communities that placed high emphasis on the perceived future of hypothetical children.

On the Right, “think of the children” is at the forefront of the movements to end abortion and diminish protections for LGBTQ+ people. On the Left, you’ll hear the same rally cry for movements that aim to reduce climate change or increase gun control. The invocation of children holds serious power. It makes us step outside our own self-focused considerations and instead wonder about a group with minimal power and autonomy.

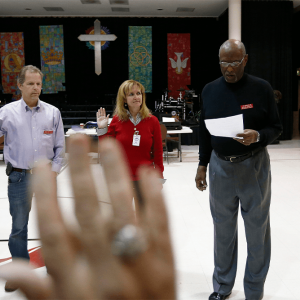

Bill Partlow (second from right), chief judge for precinct 140, at Harrison United Methodist Church administers the Election Day oath to poll workers during the 2012 presidential election in Pineville, N.C., Nov. 6, 2012. REUTERS/Chris Keane

It goes without saying that we’ve got plenty of dread to spare this year. Since President Joe Biden won the presidency in 2020, former President Donald Trump and his allies have falsely claimed that the election was rigged. Millions of Americans agree. Meanwhile, many other Americans fear how far Trump could take his authoritarian impulses in a second term. As our political culture becomes more tightly wound, the nuts and bolts of our democracy seem to be coming loose. For the average citizen, it can be hard to verify every claim we see circulated in partisan media or online. Despite election law being clear that a party can choose its nominee at convention, for example, many Republicans claimed it was “too late” for Biden to step down from his reelection campaign.

Kelly Quindlen. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

In the queer, young adult novel She Drives Me Crazy, author Kelly Quindlen employs a couple of my favorite romance tropes: A fake-dating scenario and an enemies-to-lovers story arc. But when I first read the novel a few years back, I was also delighted by all the plotlines and character traits I’d never encountered in a sapphic YA romance: The two main characters — high schoolers Scottie (star of the girls’ basketball team) and Irene (captain of the cheerleading squad) — are both Catholic, and, most significantly, their Catholicism is not in conflict with their sexuality. Both Scottie and Irene’s parents are affirming; their queerness is a nonissue for their families and their church.

Layshia Clarendon. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners. Original photo by Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports via Reuters.

“To me being Christian means f---ing s--- up,” Layshia Clarendon told ESPN’s Katie Barnes. “That’s what Jesus came to do. It means disrupting and fighting for the most marginalized people.” During the 2020 WNBA season, they helped lead players in protesting police violence against Breonna Taylor and other Black women. Clarendon helped launch the WNBA’s Social Justice Council, alongside players like Sydney Colson, Breanna Stewart, Tierra Ruffin-Pratt, A’ja Wilson, and Satou Sabally. Clarendon signed on to the Athletes for Ceasefire in Gaza, and they launched a foundation to provide grants that help transgender people access health care and other services.

Keegan Osinski. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

In recent years, the work of librarians has been sucked into the center of the “culture wars” as fascist and authoritarian movements in the U.S. attempt to censor materials, especially about queerness and racial justice. Meanwhile, justice movements have recognized how libraries are a shining example of public-funded community goods.

Jamie Grace. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

As I remember it, I was first introduced to Jamie Grace’s career while listening to a Christian radio show in 2011. At the time, she was a 19-year-old college student majoring in child and youth development, recently signed to a major Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) label, and was less than a year away from being nominated for the 2012 Grammy Award for Contemporary Christian Music Song. She was a Black woman in an industry largely made up of white men; she was open about her diagnoses of Tourette syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder at a time when I wasn’t aware of many people who were; and she was a very skilled guitar player, songwriter, and singer. As such, it seemed obvious that she had a bright future in an industry that needed new energy.

Rev. Shannon TL Kearns. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

By now, you may know that men, broadly speaking, are suffering. Despite the structure of a patriarchal society where men still reap various financial and social benefits, men are regularly facing disparate outcomes on a wide range of measures. Nearly four times as many men as women died by suicide in the U.S., 1 in 7 men report having no close friends, and men see disparate outcomes in mental health, premature deaths, and education.

Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

Over nearly three decades, Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove — a self-described “preacher, author, and community builder” — has often played Baruch to Rev. William J. Barber II’s Jeremiah. Through efforts like the Moral Mondays movement and the Poor People’s Campaign, the pair has worked to articulate what they describe as a “Third Reconstruction,” reflected in an agenda that unites the nation’s poor to confront “the interlocking injustices of systemic racism, poverty, ecological devastation.”

Attendees of the 20th Annual Patriotic Music Festival recite the Pledge of Allegiance at the Trinity Episcopal Church in New Orleans on July 1, 2018. Photo: U.S. Marine Corps by Lance Cpl. Tessa D. Watts / Alamy via Reuters Connect

At the beginning of their book, Baptizing America, Brian Kaylor and Beau Underwood return to the Christian nationalist display at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2022. No, that’s not a typo.

"A lot of psychologists, sociologists, and theologians talk about the fact that forgiveness is really for the forgiver and not the person being forgiven. But that’s not true in a lot of our American narratives [where] forgiveness is actually for the person who did the wrong, so they can be “healed.” We’ve lost the victims in that conversation."

Alessandra Harris. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

In this week’s conversation with writer and novelist Alessandra Harris, we spoke about her love of writing and when she first realized she wanted to be a writer. She was in fourth grade and the story she had written about a genie was chosen by her teacher to receive a prize. When you’re a kid, there’s just something extremely compelling about the fantasy of encountering a genie who will grant you wishes galore. Of course, as a kid, our wishes are rather innocent and self-centered: “I wish I could meet Michael Jordan,” “I wish the Chicago Bulls could win one more championship,” and, last but not least, “I wish for more wishes.” As you grow up, you realize genies aren’t real but that doesn’t prevent you from imagining what you’d wish for if you had three, two, or even a single wish. And as we age, our wishes tend to transform into a single hope for something innocent and unselfish.

Paul Ashton, a CAMRA member, samples one of the first pints drawn at the Hull Beer Festival held at Holy Trinity Church in Hull, U.K. Via Reuters.

Last week, the University of Michigan announced that it would begin selling alcohol at its football games.

For decades, alcohol sales had been largely limited at college football events, but in 2019 the Southeastern Conference began allowing its schools to sell alcohol at games. Now, more than 80 percent of the top football schools sell alcohol on game day.

In the U.S. church, opinions on alcohol seem more polarized than politics. On the one hand, many conservative and fundamentalist faith traditions treat all alcohol consumption as a sin, some going so far as to suggest that Jesus turned water into nonalcoholic wine. On the other, progressive and moderate faith traditions incorporate alcohol into church with events like beer-and-hymns, theology-on-tap, and “pub churches.”

An Israeli soldier stands next to a tank near the Israel-Gaza Border, in southern Israel on May 7. REUTERS/Amir Cohen

Ofer Cassif, whose grandparents came to Israel from Poland in 1934 as part of the Zionist movement, is a secular Israeli Marxist and a leading voice against the war in Gaza. During the first Palestinian Intifada in 1987, Cassif refused Israeli military service in the Occupied Territories and was incarcerated in military prison. In 2019, he was elected to Israel’s parliament as the only Jewish member of the Arab-majority Hadash-Ta’al party. In January, Cassif publicly supported South Africa’s petition to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to investigate Israel for violation of the 1948 Genocide Convention in its war on Gaza. In February, some parliament members tried — unsuccessfully — to impeach him.

Photo courtesy Joe Ingle. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

Anyone who has spent even a second in a prison knows it’s hell. Growing up in church, I noticed people who participated in the church’s prison ministry were both respected and feared. Respected because they were doing what the writer of Hebrews admonishes believers to do regarding those in chains: Remember them as though you were in prison with them (13:3). But they were feared because many of them had actually been in prison. Rather than the prison system or the criminal legal system being classified as barbaric, it was the prisoners who were typically understood to be barbarians.

Joe Ingle has spent a lot of time in prison. Ingle is a writer and death row minister who has been active in prison ministry since the ’70s. A native of North Carolina and a graduate of Union Theological Seminary, Ingle has dedicated his life to being present with and advocating for the 1.9 million people incarcerated in the U.S., especially the more than 2,300 incarcerated people on death row.

Photo courtesy Ashley Lynn Hengst. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners

Only 1 in 4 adults play sports each year, according to a 2015 study from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. This is despite nearly three in four respondents reporting playing as kids, and a majority of adults saying sports improved their mental and physical health ... Ashley Lynn Hengst sees opportunities for the church to help decrease those disparities and build space for more people of all ages to play sports. Hengst serves in pastoral care at All Saints Church in Pasadena, Calif., after a decade working for the Y in youth development.

Brenda Salter McNeil. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

Brenda Salter McNeil is an ordained minister in the Evangelical Covenant Church, associate professor of reconciliation studies at Seattle Pacific University, and the author of multiple books on the topic of racial reconciliation. McNeil is acutely aware of critical attitudes toward racial reconciliation and is seeking to emphasize the importance of reparations and intersectionality in her new book, Empowered to Repair. I sat down with McNeil to talk about reconciliation, Obama, and Black support for former president Donald J. Trump.

Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners. Photo courtesy Jason “Propaganda” Petty.

Every few months, a headline flashes across my news feed: “Climate change could destroy the coffee industry,” or something similar.

Even as a regular coffee drinker, what concerns me isn’t the change to my morning cup, it’s the lives and livelihoods of the farmers who plant, grow, cultivate, and prepare my coffee beans. The majority of coffee is grown in the global South, which is alsobearing the brunt of climate change. Meanwhile, a majority of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions also come from the global North.

Reggie L. Williams. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

If you’re the type of person who discusses politics online, you’re likely to have heard of Godwin’s law. In 1990, Mike Godwin, a First Amendment lawyer, invented this rule to address a common occurrence: The longer online debate drags on, the more likely someone commits the fallacy of reductio ad Hitlerum — i.e., the comparison of someone or something to Adolf Hitler or the Nazis.

Invoking Nazis, as Godwin suggests, is a lazy way of ending a debate. I also think it’s usually motivated by a shallow understanding of history and an insensitivity toward Holocaust victims.

But there’s gotta be times when referencing the Nazis is warranted, right? I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately as U.S. politics continues down the path of polarization and a segment of Christians unabashedly preach a message of domination. We need a sharper critique of Christian nationalism and the Republican presidential candidate Donald J. Trump that’s deeper than simply labeling the former group as “Nazis” and the latter individual “Hitler.” But where do we begin?

Some of the 18,000 Lohmann Classic laying hens of the Gallipool Frasses farm are seen in the the stalling area ahead of a vote to ban factory farming in Les Montets, Switzerland, September 16, 2022. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse

Reverend Christopher Carter is a virtue ethicist, commissioned elder in the United Methodist Church, and professor of theology. He has spent much of his professional and personal life learning to better the treatment of animals as part of an integrated approach to justice for all. Carter, the author of The Spirit of Soul Food: Race, Faith, and Food Justice, defines his work as a practice of “Black veganism,” which “forces us to examine how the language of animality and ‘animal characteristics’ has been a tool used to justify the oppression of any being who deviates, by species, race, or behavior, from Western Christian anthropological norms.”

Malcolm Foley. Graphic by Candace Sanders/Sojourners.

I was in high school, visiting my grandparents’ church in Peru, Ind., and the theme for the Sunday school class was “money.” The teacher was quick to bring up a verse that has always sounded like it would be a better fit in Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack than the Bible. “The love of money is the root of all evil,” the teacher said, summarizing and abbreviating 1 Timothy 6:10. “It’s not that money itself is evil. Objects, in and of themselves, cannot be evil,” he explained. “It’s a matter of the heart.” That logic sat weirdly with me and so I raised my hand to respond. “Don’t we believe that idols are objects and that they are evil? Also, doesn’t the Bible teach us to resist temptation? So wouldn’t it make sense to resist the temptation of money to avoid all the evil that comes with it?”

From left, Bella Holleman, 10, Travis Holleman, Talon Holleman, Lucas Albanese, 1, Emmett Holleman, 7, Piper Albanese, 6, Heather Robinson, Carter Robinson, 1, Christopher Albanese, 4, (not pictured), and Nash Hartstein, 6, learn farming and animal care as part of the R.O.O.T.S. (Reaching Outside of Traditional Schooling) Youth+ Development Program at the ROOTS family homestead in Georgetown, Wednesday, March 13, 2024. R.O.O.T.S. is dedicated to homeschooling and offers hands-on, integrative life-skill workshops for ages 18 months to adults. Benjamin Chambers/Delaware News Journal / USA Today Network via Reuters.

According to a study by The Washington Post, in states where data was available, homeschool students rose by 51 percent between 2017 and 2023. By comparison, enrollment in private schools rose by only 7 percent. As a homeschool alum, these statistics brought me mixed feelings. I had a beautiful, generous, enriching experience being homeschooled from fifth through 12th grade, but I know others who had the complete opposite experience. I fear that many Americans are beginning to homeschool without knowing that Far-Right, fundamentalist Christians lead most of the networks that offer resources to homeschooling families.

Photo of David Leong. Graphic by Tiarra Lucas/Sojourners.

I originally met educator and grassroots theologian David Leong in 2016 after I emailed him on a whim, telling him I was coming to visit friends in Seattle and that I’d like to meet him for coffee. I had just read an advanced copy of his book Race and Place, about churches in urban contexts, and was impressed by the conversational tone it took when addressing issues like race, class, and gentrification.