Cassidy Klein (she/her) is a journalist, writer, editor, and former Sojourners fellow living in Chicago. Find more of her work at cassidyrklein.weebly.com.

Posts By This Author

The Catholic Law Students Who Help Trans Folks Change Legal Names

Last year, Sammi Mrowka, a graduate student at San Diego State University who is nonbinary and transgender, completed the legal process for changing their name and gender marker on IDs. Mrowka, who uses “he” and “they” pronouns, participated in a name and gender marker change clinic run by law students at the University of San Diego, who helped him fill out the paperwork.

A Man-Made Mountain Proclaiming God's Love

WE STOOD AT the base of a sticky, bright mountain, a 50-foot-high altar of hay and clay and thousands of gallons of paint proclaiming “GOD IS LOVE” in chunky letters. We shaded our faces from the hazy-sizzling sky to see the white cross at the very top, blue stripes streaming down the sides, a parade of happy flowers at the base. “Say Jesus I’m a sinner please come upon my body and into my heart” is written into a giant cherry-red heart.

My friends and I were 19 years old and seeing Salvation Mountain, the folk-art stronghold, for the first time. We learned about Salvation Mountain the way most people do these days: through friends on Instagram. We drove three hours east from San Diego to Niland, a tiny census designated place in Southern California’s Imperial Valley, a desert landscape of sagebrush, sand, and brassy wind. Salvation Mountain’s artist, Leonard Knight, began building the mountain in 1984 and maintained it every day until his health began to fail in 2011. He died in 2014.

The prayer in the big red heart was what Knight prayed on the day he experienced a born-again moment and heard God call him to build a mountain proclaiming universal love to the world. When we visited, he’d been dead for a few years, and the mountain was getting cracked and worn, the paint tearing up in chunks. Knight built other structures next to the mountain, including a shaded “forest” of what he called “car tire trees”: stacks of tires for trunks and crisscrossed poles for branches, mixed with adobe and straw and painted bright colors. We quietly moved among them. “God is love” appeared again and again on the crevices and lumps, like a psalm. I felt it in my chest, that ache it takes to devote all of one’s creativity and being to God.

When Heaven Isn’t Comfort

AT 16, WHEN I finally named that I had an eating disorder, I stood in the doorway of my bedroom and Googled “patron saint for people with eating disorders.” Knowing I needed help, I first looked for guidance in my faith tradition. It began a lonely and shaky journey of figuring out what faith means in the context of my yearslong struggle, why this was happening, and what to do when answers weren’t there.

Anna Gazmarian’s Devout: A Memoir of Doubt traces her evangelical upbringing and bipolar diagnosis as she searches “for a faith that can exist alongside doubt, a faith that is built on trust rather than fear.” Growing up, Gazmarian was taught in church that depression signals a lack of faith, recalling a time a pastor told the congregation that his bipolar diagnosis was caused by his own sin. As she seeks treatment, Gazmarian engages with scripture through her experiences of mania and depression, doubt and despair, looking for validation and comfort between the lines of Bible verses.

Gazmarian’s prose is clear, engaging, accessible, and alive. With gentleness and compassion — toward herself and all who struggle with mental health — she writes about how she learns to believe that God is with her.

‘For I Was a Stranger and You Shot Me’

In a nation built on white nationalism, keeping people fearful of the “other” is useful because it keeps up the illusion of law, order, and control — the foundations of white supremacy. Crime protection is now the dominant reason people own guns. Samuel Perry and Andrew Whitehead write in their book Taking America Back for God, that White Christian nationalists tend to want a strong military, capital punishment, and oppose gun control.

Yet again and again, Christians are commanded to welcome the stranger and be not afraid. “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers,” the author writes in Hebrews 13:2. “For by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it.”

The Queer Orthodox Artist Seeking to ‘Make the World an Altar’

ACCORDING TO AN Orthodox miracle story, St. Nicholas — the fourth century archbishop who inspired the figure of Santa Claus — quieted a raging sea. When sailors were caught in a storm on the Mediterranean, they called out for help. Nicholas appeared, walking on the waves before them. He blessed the ship, and the storm calmed. This is why he became the patron saint of sailors. It’s also why Mary Marza, a queer Orthodox artist in her mid-20s who is based in Los Angeles, illustrated St. Nicholas as a “waterbender.” Waterbenders, from the animated series Avatar: The Last Airbender, can control water and its movements. This is one of many works featured on her Instagram art account, Art of Marza.

“I liked the concept of blending saints with the elements or just blending the saints with things from my favorite stories and pop culture,” Marza wrote in an Instagram caption about this portrayal of St. Nicholas.

Marza (who asked to use her art account name instead of her real last name for this article) creates digital art and stickers that blend Orthodox iconography and prayer with street art and anime. The grungy, graffiti-and-animation-inspired aesthetic of her art and its confluence with iconography is part of her longing to “[see] God in places where people assume we can’t find Him,” she wrote on Instagram.

‘Unruly Saint’ Explores What Dorothy Day’s Biographers Overlook

Day is who Mayfield looks to when her soul is parched and she longs to be renewed with God’s love “in order to keep going.” I found Unruly Saint spiritually nourishing in this way: It wrestles with the questions of how we keep going, how we keep having hope in our exhausting world, how we keep our inner light burning. “She wanted to keep a flame lit for people wondering how to break the cycles of war and oppression built into our histories and hearts,” Mayfield writes.

Can Fr. Martin ‘Build a Bridge’ Between LGBTQ Catholics and the Church?

The filmmakers tell the stories of LGBTQ Catholics and their families with gentleness and respect. “Nothing converts like stories,” Martin says in the film.

The Mystical Neon Heart Behind @PaperCutPrayers

With his knife, brightly colored paper, and the meditations of his heart, Benjamin PowerGriffin cuts “what prayer feels like, or what I yearn for it to feel like,” he said.

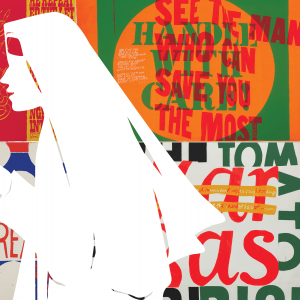

Finding Solace in the Work of the Pop Art Nun

FOR SISTER MARY CORITA, the supermarket parking lot in Hollywood she walked through each day to get to her art studio was filled with “sources.” Grocery advertisements, power lines, cracks in the asphalt, songs from car radios—all of these, to her, were “points of departure” that, when examined in a new way, tell us something about ourselves and God. “There is no line where art stops and life begins,” she wrote.

Corita Kent, a Catholic sister described by Artnet as “the pop art nun who combined Warhol with social justice,” delighted in Los Angeles’ chaotic 1960s cityscape. Her serigraphs (silk-screen prints) wrestle with injustice, racism, poverty, war, God, peace, and love in bursting neon and fluorescent lettering, transforming popular advertisements and songs into statements of hope.

“To create is to relate,” Kent wrote in Footnotes and Headlines. “We trust in the artist in everybody. It seems that perhaps there is nothing unholy, nothing unrelated.”

“She broke barriers her whole life, but always with joy,” Nellie Scott, director of the Corita Art Center, told Sojourners. “People often call her the joyous revolutionary.”

Kent was born in Iowa in 1918 and raised in a large Catholic family. Her family moved to Hollywood when she was young, and at age 18, Kent joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, who ran the high school she attended. She went on to teach art at Immaculate Heart College, becoming head of the art department in 1964.

The changes going on in both the art world and Catholicism excited and inspired Kent. In 1962, the year that Pope John XXIII convened Vatican II, Kent saw the first exhibit of Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” paintings and dove into the world of pop art. “New ideas are bursting all around and all this comes into you and is changed by you,” she wrote in Learning by Heart.

Coloradans Carry the Trauma of Mass Shootings In Our Bones

With each new instance of gun violence, creation cries out with the victims. Creation also helps us center ourselves in relation to God when God feels absent.