Da'Shawn Mosley is an editor and journalist in the Washington, D.C., metro area whose beats include the arts, LGBTQIA issues, race, and U.S. politics. He is also a fiction writer, poet, and essayist. Da'Shawn earned a B.A. in English Language and Literature from the University of Chicago, studied creative writing at the South Carolina Governor's School for the Arts and Humanities, and was featured in the PBS documentary Becoming an Artist. His fiction earned him the 2019 A Suite of One's Own: A Writer's Residency, awarded by Kiese Laymon, and he has been published in America magazine and The Adroit Journal.

Posts By This Author

‘Dead to Me’ Should Be Dead to No One

I AM CONVINCED that 20 years from now, Dead to Me will finally get the praise it’s due, ending up in some culture magazine’s ranking of the best TV comedies of all time. (I’m giving you a head start, Sojourners: Beat Rolling Stone to the punch.)

Dead to Me, a Netflix show about a woman and her children grieving her husband after he is killed in a hit-and-run, is sort of what you would get if you merged another destined TV classic from Netflix — Grace and Frankie — with the Joan Didion memoir The Year of Magical Thinking and then sprinkled in a police investigation. The show is laugh-so-hard-you-cry funny and yet is driven by situations that would probably make you weep if you paused to think.

I barely had time to do that, though, because Dead to Me is a twisty thriller centered around a hilarious opposites-attract friendship between the widowed protagonist Jen (Christina Applegate) and a jolly woman she meets at group grief therapy named Judy (Linda Cardellini). Throw in some great meditations on friendship, forgiveness, motherhood, absence, and why everything is so screwed up if the whole world is in God’s hands; a Christian youth dance troupe; and an astounding performance by the actor James Marsden, and you have one of the best TV shows ever.

Finding the Imago Dei in ‘P-Valley’

P-VALLEY IS A DRAMA about employees of a fictional strip club in Mississippi called The Pynk. Watching the show, which Starz has renewed for a third season, gives me déjà vu. In the opening minutes of the first episode, we see a neighborhood overtaken by a flood, the camera eventually focusing on a floating suitcase — which a woman who looks like she just survived a hurricane grabs. I’m reminded of Toni Morrison’s titular character Beloved, who “walked out of the water”; it’s all instantly reminiscent of the Southern, sin-filled aura of stories by Flannery O’Connor. A few minutes later, I’m hit with production design as colorful as that of the TV show Pose — unabashed theatricality.

This description should feel as dizzying as twirling around a stripper pole — that’s the inevitable impact of the artistic and spiritual heft P-Valley wields. The show, which is an adaptation of a play by Pulitzer Prize winner and Tony Award nominee Katori Hall, is about nothing less than free will. Hall explores complex topics such as sex work, abuse by men, abortion, and homophobia. Here in the Mississippi Delta, viewers get to know a mostly Black community trying to live as freely as the Constitution of their nation built by slaves declares white men should.

The Gift of ‘The Good Wife’

THE BEST WORD to describe The Good Wife (2009-2016) in comparison to its prestige TV peers may be generous. Its predecessors (The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, Breaking Bad) in the TV golden age of the early 2000s set the expectation that serious dramas on the small screen have seasons of about 13 episodes each and air on platforms you must pay for (cable channels such as HBO and AMC, and now subscription streaming services like Netflix). In contrast, less-than-highbrow thrillers with a bit of humor, like the police procedural NCIS, pour out nearly double that amount of content per season on free network TV.

But The Good Wife on CBS defied that expectation. Here was a network drama that was just as revelatory about humanity as the best of cable’s offerings while also being hilarious, accessible, and plentiful (seven seasons of no fewer than 22 episodes each). In a world where complex female TV protagonists are still too rare, revisiting The Good Wife is a holiday break well spent.

A Family’s Resilience in the Face of Discrimination and Surveillance

IT'S CLICHÉ AT this point to call television dramas with rich storytelling and emotional depth (think The Wire and Breaking Bad) novelistic. But no show may be more novelistic than Pachinko on Apple TV+. Like the book by Min Jin Lee on which it is based, Pachinko encompasses four generations of a Korean family, following them from Korea to Japan throughout much of the 20th century. But while the book moves linearly, the TV show shifts back and forth from 1989 to the 1920s onward, with one actor (Minha Kim) playing the protagonist Sunja when she is a young woman and another (Oscar-winner Yuh-Jung Youn from Minari) when she is a grandmother.

Hollywood often seems to assume that viewers need stories that match our limited comprehension. But lately there’s been a shift, with Korean artistry initiating the move. Hollywood, uncharacteristically, embraced the South Korean thriller Parasite, the first non-English-language film to win Best Picture at the Oscars, and went equally wild for the South Korean TV drama Squid Game, the first non-English-language show nominated for Screen Actors Guild Awards (winning three). Subtitles—kisses of obscurity in Hollywood—become something sweeter: Trust? If so, Pachinko puts double the faith in non-Korean- and non-Japanese-speaking viewers, subtitling the Korean in yellow and the Japanese in blue and juxtaposing the colors when both languages flow from a character's mouth in a single line of dialogue. At times, the bottom of the screen resembles Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.”

Perfection Is the Lord's

ONE OF MY favorite quotes is from the novelist Taiye Selasi—or, more specifically, Selasi’s editor. Selasi was nervous before the release of her debut novel, Ghana Must Go. How would it be received? What if it wasn’t perfect? She called her editor, and the advice was simple: “Perfection is the Lord’s.”

This came to mind as I watched the final season of Pose, a scripted FX drama focused on the New York City ballroom culture, in which groups of LGBTQ+ people influenced by the fashion industry compete in dance, runway, and posing competitions. Pose isn’t just about trans and queer people as they try to survive the AIDS epidemic; it stars trans actors. It’s moving not just because of its subject matter but also because it’s unafraid to make what many scholars consider a grave mistake in art: crossing the line into sentimentality.

Let dialogue be cheesy. Let characters’ instincts to battle it out on the dance floor after every tragedy be as ridiculous as most musical numbers in Glee. Let feelings be unrefined. These seem to be Pose’s creeds, and I often eyerolled at the show’s adherence to them. And yet I kept watching. It was—there’s no other word for it—love.

Kendrick Lamar Is Forcing Us to Reckon With His Brokenness

All the glory Kendrick Lamar has received for his three Grammy Album of the Year nominated works of Christ-influenced, socially conscious rap masks a difficult truth: To be a fan of his music, you have to disregard its desecration of women.

Discomfort May Be the Point

WHEN I THINK about the 2015 HBO miniseries Show Me a Hero, the person who first comes to mind is Nick Wasicsko. This is understandable: According to its HBO blurb, the politician is the show’s main protagonist. But this scripted drama is about the real-life 1980s and ’90s struggle for public housing in Yonkers, N.Y., when low-income people of color worked for integration and the city government resisted—even as daily contempt-of-court fines threatened to bankrupt it. So, it feels weird to focus on the white Mayor Wasicsko, although he (eventually) fights for the public housing too.

This discomfort may be the point. “The thing I don’t buy anymore,” said the show’s co-writer, David Simon (The Wire, Treme), “is if we elect the right guy, the great men of history, that’ll save us. ... Our problems are systemic, and we’re going to have to solve them as people.”

Kanye West Is Not Done Changing the World, for Better or Worse

Looking at Kanye West can be both difficult and easy. Easy because of his genius: how he put Chicago on the map as a hub for brilliant rap music, widened the lane for non-gangster rappers, and somehow made tunes seriously considering Jesus so sonically innovative and catchy that some become radio staples, paving the path for Kendrick Lamar and Chance the Rapper. Difficult because of his public antics: the outbursts, the flamboyance, the drama. Recently Kanye’s displays have even become dangerous, harassing his wife Kim Kardashian, who has filed for divorce, and threatening her rumored boyfriend Pete Davidson.

‘Tehran’ Is a Timely Look at Life Beyond the U.S

THE POWER OF the TV drama Tehran, about an Israeli spy who was born in Iran to a Jewish family and returns to her birthplace to help destroy a nuclear reactor, lies partly in how it parallels reality. On the other side of the screen, President Joe Biden continues to face the fallout of President Donald Trump’s decisions to withdraw the United States from the Iran nuclear deal and recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, while tensions between Iran and Israel simmer.

But relevance alone doesn’t win an International Emmy Award for Best Drama. With her lifelong ties to both Israel and Iran, Tehran’s hacker-agent Tamar Rabinyan is a unique protagonist, and Tehran perfectly executes the thrills and twists that draw people to the spy genre. The show also is violent—guns, blood, an attempted rape that ends with the killing of the attacker, and a shot of a man hanged from a crane, presumably executed by the government. The more I watched, the more I felt a pang in my chest, wondering whether Rabinyan would survive.

Tehran is not all stress, though—at least not for the viewer. Rabinyan’s family members become entangled with the show’s plot in a pleasurably Shakespearean fashion, mirroring each other and possessing information their kin may not know but the viewer does. A romance grows between Rabinyan and an Iranian hacker named Milad. When the show pauses the action to linger on characters and personal relationships, we can reflect on the humanity of Muslim and Jewish lives. Even clichéd techniques provide this opportunity, such as a scene in slo-mo—which I would have foregone for regular-speed footage—of Iranian university students protesting restrictions imposed by their government as other students counterprotest in support of the government’s conservative stance.

Seeing Ourselves On Screen

SOME TV SHOWS are as great as our greatest literature. Programs such as The Sopranos, The Wire, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad are Dickensian in their sprawl and Shakespearean in their tragic characters’ deceptions. But one show in this current Golden Age of television is the most oft-overlooked of its peers, one whose greater feat—or unfairness to screenwriters—is that it’s not scripted. I’m talking about A&E’s reality show Hoarders.

I’m not kidding. What often draws people to watch those suffering from hoarding disorder and the psychologists, professional organizers, and loved ones trying to help them overcome mental illness is the typical reality TV magnet: Seeing the life of someone worse off than you. But there’s more to Hoarders than that. A good episode is nothing less than a short story similar to those by Alice Munro, vivid in its deep analysis of real life, family dynamics, and psyches in danger and repair. Almost every night for the past month, watching has been like studying fiction writing in some of the best (and cheapest) creative writing courses I’ve ever taken.

A Buddy Comedy With Heart

I WOULDN'T WISH on anyone the narrative dilemma facing the writers of United States of Al. The CBS show is a buddy comedy about a young Afghan man who finally gets a visa to come to the U.S., thanks to a Marine, Riley, for whom he was an interpreter during the Afghanistan War, whose life he saved, and with whom he’s living in the States. But United States of Al’s second season, with an Oct. 7 premiere, may need to encompass even more grief than its predecessor. The U.S. has withdrawn from Afghanistan, and the Taliban has taken over. We’ve seen the video of Afghan people trying to hold on to a U.S. military plane as it takes off, the clip ending right before some of them fall. Human remains were later found in the plane’s wheel well. What will happen when United States of Al’s protagonist sees that video?

‘Freedom’ Is Everywhere, But What Does It Mean?

Aretha Franklin, Simone Biles, and Britney Spears deserve some respect.

Aretha Franklin Biopic ‘Respect’ Highlights Dangers of Patriarchy

Respect is a must-see work, moving in its revelation of a superstar whose glow many of us have seen, the shadows surrounding them more hidden from view. Ms. Franklin was not just an incredible singer but also a civil rights activist like her father.

Mary Lou Williams' Jazz Is for the Masses

FROM THE 1920s until her death in 1981, Black jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams injected energy and innovation into the genre and, via three jazz Masses composed after her conversion to Catholicism in the 1950s, into the church. Still, her music is sometimes overlooked, while the popularity of male jazz musicians’ work—including her mentees Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker—persists.

In this century, Deanna Witkowski is amplifying Williams’ works of music and faith. Witkowski is a jazz pianist herself, inspired by Williams, and a doctoral student in the jazz studies program at the University of Pittsburgh. She is restoring and recording general and liturgical compositions by Williams, some of which haven’t been recorded since 1944. And she has written a biography of the pioneer, Mary Lou Williams: Music for the Soul (Liturgical Press). Witkowski spoke with Sojourners associate editor Da’Shawn Mosley about the book and its namesake.

Da’Shawn Mosley: How did you become interested enough in Mary Lou Williams to write a biography of her?

Deanna Witkowski: In 2000, Dr. Billy Taylor, a jazz musician himself and the judge from a jazz piano competition I had played the year before, contacted me and said, “Come bring your quintet to play at the Mary Lou Williams Women in Jazz Festival at the Kennedy Center in the spring.” And so of course I said, “Yes, I would love to do this.” And then thought, “I really don’t know Mary Lou Williams’ music.” That’s a very common thing, even among jazz musicians or aficionados. She has this reputation [as] this great pianist and composer who wrote big-band music for Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman and mentored all these famous jazz musicians—so we know Thelonious Monk. But her compositions aren’t very well known.

City of Brotherly Justice?

PENNSYLVANIA CAPTURED THE attention of many of us this year via the superb crime drama Mare of Easttown on HBO, but there’s another incredible television show set in the state that we should be watching. I’m talking about Philly D.A., on PBS. An eight-episode documentary series focused on activist-attorney Larry Krasner’s unusual election to the role of Philadelphia’s district attorney and his desire to drastically reform the office, Philly D.A. is gripping and revelatory in how it explores the intricacies of his efforts. In the social justice sphere, we have big ideas of how government systems and traditions can be altered and abandoned, but most of us never get the chance to implement them. Philly D.A. depicts a staff doing just that and shows how difficult it is.

We see assistant DAs and staff members who have worked in the office for years, for several administrations, and have households and families—we see them be fired because they’re believed to be too entrenched in how things were done in the past. We see surviving loved ones of murdered citizens wonder why, after many years of the DA’s office recommending the death penalty, Krasner does not see it as a good solution. We see judges and other officials express their fear that, in the pursuit of innovation, all aspects of a functioning system are being tampered with, negatively affecting the city’s safety.

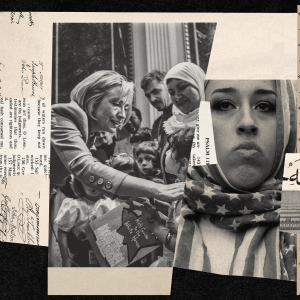

U.S. Politics' Narrow Gate

EXCEPT FOR ABRAHAM LINCOLN and Thomas Jefferson, every president of the United States was or is a professing Christian.

Only in the case of John F. Kennedy, it seems, has a president’s Christian faith counted against him in the opinion of a significant number of citizens, and in Kennedy’s case it was because he was Catholic rather than Protestant. The Christian belief of public officials in any branch of national, state, or local government hardly ever raises concern among the U.S. public. But the opposite is true when it comes to Muslim officials.

Many conservative Americans say they fear that the U.S. will become a nation influenced by Islamic tenets instead of Christian ones. Commentators on Fox News often express alarm about sharia (Islamic law). Jeanine Pirro, host of the network’s Justice with Jeanine Pirro, accused Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., a Muslim woman of Somali descent, of supporting Islamic rule in the United States. Omar and Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan are the only two Muslim women ever elected to Congress, and two of the three Muslims ever to serve in the U.S. legislature; Twitter users criticized Omar for wearing a hijab and Tlaib for wearing, at her congressional swearing-in, a traditional Palestinian dress called a thobe, made by her mother. Another Fox News host, Pete Hegseth, said that, based on how Tlaib “talked about President Trump having a hate agenda, I could, therefore, look at her and say that she has a Hamas agenda.” The Associated Press had to debunk the claim that Tlaib’s thobe was a “symbol of Hamas terrorists,” a sign that many Americans may have believed it to be true.

The alienation and hate go even further. A Florida Republican politician said in a fundraising email that falsely claimed that Omar worked for the nation of Qatar, “We should hang these traitors where they stand.” Another man called Omar’s office and said he would “put a bullet in her skull.” Following the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, when lawmakers were still in the building trying to certify President Joe Biden’s election, Tlaib discussed on the House floor her constant fear due to the death threats she regularly receives.

“I worry,” she said, “every day.”

The Book of Abby

THE PROPHET JOB had a hard life, but I think even he, if listening to Abby’s story, would say, “Damn.”

He’s not listening to her troubles, though: Abby’s therapist is. No, wait, she’s not listening either, for a reason that will spur Abby’s friends to joke about just how sad Abby’s life really is.

I’m describing Work in Progress, a scripted comedy produced by Showtime and co-written by Tim Mason, Lilly Wachowski (The Matrix, Sense 8), and Abby McEnany, who stars as a fictionalized version of herself.

“Abby is a mid-forties self-identified queer dyke whose life is a quiet and ongoing crisis,” Showtime’s website describes, not revealing that Abby lives with OCD, washing her hands repeatedly and recording her life meticulously in notebooks, in case she forgets anything she’s ever done. It doesn’t reveal that Abby, throughout much of her life, has been called Pat—a reference to the Saturday Night Live character from the early ’90s—and is often mistaken for a man, asked to leave public bathrooms, and struggles with her weight. It certainly doesn’t reveal what we learn in the first few minutes of Work in Progress: In a couple of weeks, if Abby’s life doesn’t get better, she plans to take her own life.

'Tough As Nails' Plays to Kinder Rules

IN MIDDLE SCHOOL I emailed CBS and asked them to make a teen version of their reality show Big Brother, in the hope that they would cast me and I could schmooze and deceive my peers to win the contest’s $500,000 prize. Schmooze and deceive weren’t my bright ideas: They formed a strategy I had seen succeed on previous seasons of Big Brother and Survivor, as clueless heroes were undone by ruthless, money-hungry, victorious villains. Even CBS’ clean-fun competition The Amazing Race had enabled contestants to backstab another team for $1 million.

So it’s unexpected that the network’s newer prime-time contest Tough as Nails plays to kinder rules—and that it has become part of my mostly drama-filled viewing habits. Twelve Americans with some of the most strenuous jobs that exist (welder, farmer, firefighter, ironworker, and more) vie in team and individual challenges to see who’s the hardest and smartest worker. As an artsy guy whose most physically demanding professional activity is typing, I would not have pictured myself in the Tough as Nails fan base. And yet, here I am.

Ruby Sales: “So What Is It They're Asking You To Do?”

IF ASKED “What era would you time travel to if you could?” many young Black and brown and Indigenous people would answer in a flash, “None of them.” Why? We’re too aware of the past and what it means for us today—we tweet about the results of American slavery and can break news of the latest injustice to emerge from centuries-long hatred of nonwhite skin faster than MSNBC. We feel the negative effects of history enough each day to not want to go back there.

But maybe we should. If all we see of ourselves on TV and social media is us sick, oppressed, or dead, what other understanding of ourselves do we miss? How can we remember that we are greater than the damage done—that our history holds more than that and so might our present?

Ruby Sales, founder and director of the SpiritHouse Project, helps young people invested in faith and social justice see themselves through the lens of their divine wealth and boundless potential rather than through eyes dimmed by media and versions of history shaped by white supremacy. Sales, who by age 17 was a Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee member registering people to vote in her home state of Alabama, has a Master of Divinity degree from the Episcopal Divinity School and is a preacher, speaker, and intergenerational mentor on racial, economic, and social justice. I spoke with her in December by phone. —Da’Shawn Mosley

Da’Shawn Mosley: I watched a YouTube video of you speaking in 2015 at St. Albans Episcopal Church in D.C. and was struck by what you said about today’s youth: that the most recent generations have incredible insight but haven’t lived enough to have hindsight.

Ruby Sales: Now that I’m working with young folks in my fellowship program and have had some time to weigh how things have changed from the ’90s to the 2000s, I think young people lack insight also. When you have been raised in a technological age, when history is no longer lived experience but is created on social media and reproduced through technology, I think that long-term memory is affected, as well as the ability to empathize and connect with human suffering. There is a difference between being able to theorize about human suffering and being able to feel it. All of these are challenges faced by generations raised in a technocracy—the decimation of history, of who we are as a people.

A Latinx Family's Hilarious, Relatable Journey To The American Dream

A GENUINE HEART can overcome many a fault in the television landscape. I don’t just mean from a plot perspective, in which a character’s good nature helps them exit a situation their good nature got them into in the first place. But also from the perspective of capturing viewers’ attention—protagonists whose warmth we feel through the screen in a way that makes us forget a show’s turnoffs: occasional weak jokes, predictable storytelling, trite dialogue—all of which the Netflix show Gentefied contains.

And yet Gentefied, a half-hour comedy with a title that plays on the words gente (Spanish for “people”) and gentrified, has quickly become a favorite. The Mexican American Morales family at its center are hilarious and relatable. Casimiro (or “Pop,” as his grandkids call him), owner of a taco restaurant in LA’s Boyle Heights neighborhood, struggles to keep his establishment open as he falls further behind on its rent and gentrification makes the neighborhood less and less familiar. Meanwhile, Casimiro’s granddaughter Ana seeks to become a successful artist; grandson Chris, a trained-in-Paris chef; and other-grandson Erik, a dependable dad. Haunting their family home are Chris’ financially stable yet estranged dad and memories of Pop’s late wife. In these tough situations full of grief (Donald Trump’s xenophobic presidency does not help), Gentefied’s creators Linda Yvette Chávez and Marvin Lemus highlight the humor and love of the Morales family journey.