Diana Butler Bass blogs at Christianity for the Rest of Us and The Huffington Post, and is the author of A People’s History of Christianity: The Other Side of the Story.

Posts By This Author

Why I Don’t Fear Denominational Schisms

IN THE DECADES before the Civil War, three of the nation’s largest Protestant denominations—Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists—split over slavery, biblical interpretation, and abolition. Historians have long claimed that these denominational schisms paved the way for a national rift. Once these Protestant churches failed to hold together, breaking into regional bodies of South and North, wrote C.C. Goen in Broken Churches, Broken Nation, “a major bond of national unity” dissolved and hastened America’s warring fate.

As the churches divided over slavery then, so they are dividing over sexuality and gender now. Many of the biblical arguments and hermeneutic approaches once used to support slavery are now employed to reject the humanity, gifts, and dignity of women and LGBTQ persons. If you read 19th century sermons or tracts from Southern Presbyterians, for example, you only need to swap out a few words and you have a blog about how the Bible doesn’t allow women to preach or gay and lesbian couples to marry. Mark Twain once quipped that history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. In this case, however, the similarities are so striking that history appears to plagiarize itself.

In recent years, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and Presbyterians have all faced contentious splits over these issues, and now the United Methodist Church—the largest mainline Protestant denomination—is struggling with the same.

History may plagiarize, but it will not repeat. These denominations aren’t as significant as they once were, culturally or politically. The Baptists not only split over slavery but remained permanently divided in Northern and Southern branches, then divided and divided again. The Methodists reunited in the 20th century, as did the Presbyterians. But for all their remarkable contributions, neither denomination regained its former status.

A Horizontal View

JUDAISM AND CHRISTIANITY urge followers to seek heavenly things, to model their lives on heavenly virtues, and to have hope in heaven. In the New Testament, heaven most often appears as the “kingdom of heaven,” God’s political and social vision for humanity, an idea that Jesus uses to criticize the Roman Empire’s oppressive domination system. Jesus’s own prayer, “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10), seeks to align earthly ethics with the divine order of God’s own dwelling place. Heaven is an intrusive reality, the ever present realm of God hovering all around, sometimes even synonymous with God, as Marcus Borg writes. The Bible says the kingdom of heaven “has come near” (Matthew 4:17), and if heaven is nearby, so is God. Heaven is here-and-now, not there-and-then.

To speak of heaven, therefore, is another way to speak of the earth. But the vision for the earth that “heaven” presents is not in keeping with the world’s violence, oppression, and injustice; rather, it is an alternate vision of peace, blessing, and abundance, the world as God intended it to be. Heaven has been depicted as far away, unattainable in this life.

Can Christianity Be Saved? A Response to Ross Douthat

In recent days, conservatives have attacked the Episcopal Church. The reason? The church has just concluded its once every three-year national meeting, and in this gathering the denomination affirmed a liturgy to bless same-sex unions. Conservatives assert that the Episcopal Church's ever-increasing social and political progressivism has led to a precipitous membership decline and ruined the denomination.

Many of the criticisms were mean-spirited or partisan, continuing a decade-long internal debate about the Episcopal Church's future. However, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat broadened the discussion, moving beyond inside-baseball ecclesial politics to ask a larger question: "Can Liberal Christianity be Saved?"

The question is a good one, for the liberal Christian tradition is an important part of American culture, from dazzling literary and intellectual achievements to great social reform movements. Mr. Douthat recognizes these contributions and rightly praises this aspect of liberal Christianity as "an immensely positive force in our national life."

Despite this history, however, Mr. Douthat insists that any denomination committed to contemporary liberalism will ultimately collapse. According to him, the Episcopal Church and its allegedly trendy faith, a faith that varies from a more worthy form of classical liberalism, is facing imminent death.

When Religion and Spirituality Collide

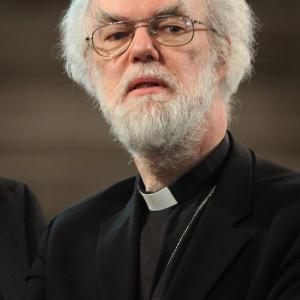

Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, the leader of the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion, recently announced that he would step down by year's end. A few days later, the Church of England rejected a Williams-backed unity plan for global Anglicanism, a church fractured by issues of gender and sexual identity. The timing of the resignation and the defeat are probably not coincidental. These events signal Anglicans' institutional failure.

But why should anyone, other than Anglicans and their Episcopal cousins in the U.S., care? The Anglican fight over gay clergy is usually framed as a left and right conflict, part of the larger saga of political division. But this narrative obscures a more significant tension in Western societies: the increasing gap between spirituality and religion, and the failure of traditional religious institutions to learn from the divide.

God in Wisconsin: Scott Walker's Misguided 'Obedience'

Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords: Speaking for the Soul

The Real Housewives of Proverbs 31

Civility: The Problem of Being Nice

Is Western Christianity Suffering From Spiritual Amnesia?

Baseball, Tiger Woods, March Madness, and the American Soul

Advent: Apocalypse Now?

Psalm 109:8 -- A Prayer to Destroy Obama?

Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition

Thou Shalt Not Abuse the Ten Commandments

ABC's Nightline has been running a series on the Ten Commandments in which they explore the issues and dimensions of each commandment in contemporary society.