Drew Elizarde-Miller is an erstwhile pastor and the National Coordinator of the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines-U.S. Network. Drew is based in Portland, Ore., where he lives with his partner Trisha and dog Pancit.

Posts By This Author

The Evasive Nature of Declaring 'War' on a Pandemic

The way presidents and governments use language reflects the society they want to construct — and for the United States, presidents have long attempted to build a narrative that hides he real impacts of war and makes the United States look the part of a noble hero. Crisis and pandemics don’t start wars, and they won’t end war, but the United States may use crisis to beat the drums of war.

Filipino Churches are Resisting Corrupt Government. The U.S. Church Should Take Notes

Impeachment suggests charging a president with misconduct that would disqualify them from public office — that’s not what Filipinos as asking for. Unseating Dutarte from office implies that there is a need for people power — a movement to assert democracy and not merely hang ones hopes in a system that has been known to fail or serve only a few. Impeachment calls the government to act, “unseat” calls the general masses to protest and hold government accountable.

This Human Rights Activist Was Detained, Interrogated, Denied Entry. Why?

For a country that so often claims to purport liberty and democracy, the displacement of 400,000 people in Marawi and the 20,000 killings under Duterte’s drug war should concern the United States. But in the treatment of Jerome Aba, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents enacted an ideology of scarcity, Islamaphobia, and “America First.” It is an ideology that carries international U.S. military intervention and control as the key to safety. And as a Muslim and peace advocate, Aba was a threat to that and treated as an “enemy combatant”.

Under Trump and Duterte, Christians Must Rise Against Militarism

The heightening militarism following Trump’s invitation to Duterte is neither unrelated nor isolated from U.S imperialism in the Philippines — a history that is often manipulated through religious language.

5 Things That Could Stop the Drug War Killings in the Philippines

Philippines Drug War Protest on October 10, 2016 at the Philippines Consulate General NYC. Photo by Vocal-NY / Flickr.com

On April 10, New York Times journalist Daniel Berehulak received the Pulitzer for his photojournalism on the drug war in the Philippines. His gritty depiction of the killings in the Philippines, under President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war, is perhaps fitting for Holy Week — calling to mind stark images of blood and crucifixion.

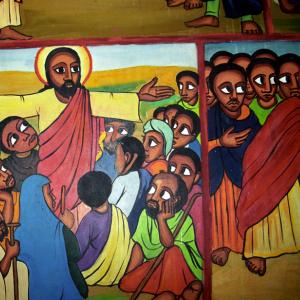

Why We Need a Filipino Jesus

At an evacuation hosted by the United Church of Christ in the Philippines, I met the “suffering but struggling Jesus” when I spoke with Bai Bibyaon, the only female chieftan of the Lumad. Bai is over 90 years old, and, like Christ fleeing angry crowds and the surveillance of the Roman Empire, Bai has fled her ancestral land from the violence of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, all to be in sanctuary with her people, the Manobo. She told me, “Our ancestral land, on the Pantaron Mountain, is the only remaining virgin forest in Mindanao. All we want is peace, and to be in our ancestral lands without the Armed Forces of the Philippines or mining companies destroying our land."

Ferguson: Between Jesus and Barabbas

In an intimate conversation between Jesus and his disciples, just before Jesus predicts that Peter will deny him three times, Jesus asks Peter, “Will you lay down your life for me?” As Jesus’ crucifixion approaches, his question to Peter becomes reality, and the people who know of Jesus or his movement must make a choice — to suffer and die with Jesus, or to slip away in fear and passivity — to welcome Christ, or to reject Christ.

Peter is certainly not the only one to face this decision. Judas must choose to betray Christ or not; the high priests must choose between power and mercy; Pilate must choose the approval of the people or trust his own conscience. These individuals, however, do not stand alone in their decision-making, but among one of the strongest but often overlooked characters in Scripture — the crowd. As Jesus stands before Pilate, it is not Pilate who truly holds power — it is the raging crowd before him that demands for the freedom of Barabbas and the crucifixion of Jesus.

When looking back on the crowd’s decision, it is easy to see how wrong it was until we begin to ask where we stand among the crowd in our time. In the case of Ferguson and the grand jury’s decision on Darren Wilson, most of us stand in the crowd, waiting to see what the grand jury and the state may do while we decide what we must do. All eyes are on the jury, yet many of us who are watching realize that the real power does not reside in Gov. Jay Nixon or the grand jury, but in us. Just as it is the crowd who sways Pilate to crucify Jesus, so it is we who can determine whether justice comes in Ferguson and everywhere where racism exists. As bell hooks writes, “Whether or not any of us become racists is a choice we make. And we are called to choose again and again where we stand on the issue of racism in different moments of our lives.” Today, we have another choice. The grand jury is under the spotlight, but we are all responsible.

White People Need a Non-White Jesus

In the wake of Megyn Kelly’s statement that “Jesus was a white man,” critics have quickly and unanimously responded that Jesus was not a white man.

Rev. Laura Barkley debunked Kelly’s statements for Sojourners, noting that Jesus “was a Palestinian Jew in first-century Nazareth.”

Fast for Families -- Remembering Our Bodies, the Land, and Community

On Sunday, with lots of turkey, stuffing and pie still in the fridge, I joined the #Fast4families movement, abstaining from food and drink for a day in order to pray for immigration reform. At first, I hesitated because it wasn’t necessarily my ideal time for fasting — besides being Thanksgiving weekend, I was about to enter the last two weeks of my academic semester, the most mentally demanding and sleep-depriving time of my year.

Quickly, however, I realized that all the worries I had going into the fast came from my white, privileged, experience of the world. Because of my privilege, I could believe in the illusion that immigration reform does not affect me.

The more I thought about this, the more I concluded that my reasons for not fasting were pointing to the ugliness of my own privilege and participation in racism, for if we do not actively challenge racism, we affirm it. This is what Jesus was getting at in Matthew 12:30, when he said, “Whoever is not with me is against me, and whoever does not gather with me scatters.” Jesus does not call us to merely advocate, but asks us invest our whole lives.

My hesitancy to fast was also a reflection of Western spirituality, which privileges the mind over the body and knowledge over action. Before I knew about the fast, my inclination was to spend my day’s energy on academic work, ignoring the body I live in, as well as those bodies that suffer far more than I ever would under an oppressive immigration system.