Faith-Marie Zamblé is an artist, writer, and M.F.A. candidate in dramaturgy and dramatic criticism at the Yale School of Drama.

Posts By This Author

The Solar Power of the Dog

“DO NOT LOOK AWAY. Do not avert your gaze. Do not turn aside.” These words met me a few weeks ago via ecologist Joanna Macy’s ever-relevant book World as Lover, World as Self. I love these words, even though their charge is not an easy one. Looking at what is, without turning away, without aversion, takes incredible strength of will, especially in a culture that banks on our inability to pay attention or handle despair. Nonetheless, for Macy, the illumination of sustainable futures is impossible without first facing our grief. Which brings me, in an extremely roundabout way, to Jane Campion’s film The Power of the Dog and Lorde’s 2021 album Solar Power.

Glennon Doyle Was a Lifeline—Just Not the One I Expected

WHEN I PICKED up Get Untamed—a journal based on Glennon Doyle’s best-selling memoir Untamed—at a secondhand bookstore, I was, as the kids say, down bad. Real bad. A year of overscheduling, overcommitting, and underhydrating had turned me into the caretaker of a creative and existential abyss. In that bookstore, I was reaching for more than a how-to book. I was reaching for a lifeline. And I found one—just not in the way I expected.

Doyle emerged onto the nonfiction scene with Carry On, Warrior in 2013, followed by Love Warrior in 2016. The latter book was raw and vulnerable, detailing the dissolution and resurrection of Doyle’s first marriage. Acclaimed by Oprah, Brené Brown, and Elizabeth Gilbert, Love Warrior celebrated love’s ability to overcome all obstacles—from addiction to internalized misogyny—in a marriage. Then Doyle met retired professional soccer player Abby Wambach. Doyle and her husband divorced. Now Doyle and Wambach are, by all accounts, happily married. The events leading to this form the basis for Untamed.

Walled-In Tragedy

“NOTHING EVER HAPPEN under ground in Louisiana / Cause they ain’t no under ground in Louisiana. / There is only / under water.” With these words, playwright Tony Kushner draws us into the conundrum at the heart of the musical Caroline, or Change: How do you swim when you’re already so far below sea level? Caroline Thibodeaux (played by Sharon D Clarke in Roundabout Theatre Company’s Broadway revival production) is our eponymous anti-heroine, a 39-year-old maid and divorced mother of four, trying desperately to answer this question in every area of her life.

Based in part on Kushner’s own childhood, Caroline, or Change speaks through the sounds of Motown, gospel, klezmer, and blues—handily packaged by composer Jeanine Tesori—to tell the story of an uneasy friendship between Caroline and her employer’s son, 8-year-old Noah Gellman. The Gellman home becomes a larger metaphor for a country stratified by a brutal socioeconomic caste system, emphasized in the staging by a multilevel set. The structure of 1960s America is made visible, placing each character in predetermined roles, and thus unable to truly see each other.

America May Not Have Bread, but it Sure Has Circuses

THE MET GALA is fascinating. Part chaos and part fundraiser, the Gala has created a treasure trove of cultural touchstones and meme-worthy content over the past few years. Created in the 1940s to benefit the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, the Gala is, at its core, a paean to the sartorial arts. In many ways, it’s the gift that keeps on giving, especially if you, like me, are not opposed to a lot of pomp and very little circumstance. However, in the thick of my 2 a.m. behind-the-scenes-at-the-Met video binge, a thought occurred to me that I’ve been turning over ever since: America may not have bread, but it sure has circuses.

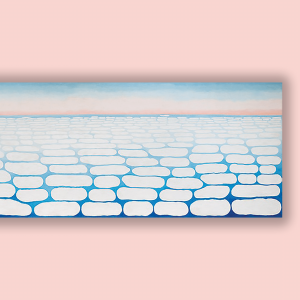

Exploring Grief and Change With Georgia O'Keeffe

NEARLY EVERYONE I know is moving. Homes that were once beloved, or at least tolerable, now represent forced encampment. Like rats departing a sinking ship, many of us are running from the wreckage of 2020 with little more than the clothes on our backs and enough money for a security deposit. Change is in the air. Yet, as the adage goes, “The more things change …” Cells renew, but bones remain.

The image on a postcard on my desk, taken by the infamous Carl Van Vechten, is Georgia O’Keeffe next to one of her iconic cow skulls. Her eyes are closed as she cradles the skull in her hand and leans her head against it. The gesture, almost reverent in its grace, seems to acknowledge the animal who once was. The picture is a study in contrast, much like O’Keeffe’s life. According to the postcard, the photo was captured at O’Keeffe’s New York penthouse in 1936. By this point, she’d already made her first pilgrimages to the American Southwest, a region that would provide her with artistic inspiration until her death in 1986. It was also a refuge from the stress of her marriage to the influential photographer and philanderer Alfred Stieglitz. Maybe it’s fitting then that one of the few O’Keeffe pieces I’ve seen in person is related to her attempts to find sanctuary.

A Layer of Sterility

A FEW WEEKS ago, a friend invited me to New York with them to see some art. After taking the commuter train down from New Haven, Conn., we made our way through Grand Central Station, onto the subway, then up a steep escalator, eventually arriving at the gallery’s entrance.

Visiting Manhattan during a pandemic is a fascinating study in strangeness. The Times Square subway station is so quiet you can hear your own footsteps. Sweaty players duel on a basketball court, and I am shocked by seeing unmasked faces in public. Even the experience of gallery hopping, one that used to be extremely familiar to me, feels askew. A few of the places we visit require a signed liability waiver before entering. Each desk is punctuated by a giant bottle of hand sanitizer. This imposing combination does not stop me from enjoying the work I see, however. There are many juxtapositions of color and line that sparkle in my brain. An image of a fabric store, itself made out of fabric, proves especially delightful. I see some art books that I think I might like to have in my home. I am glad to have gone.

Michaela Coel's Latest Project Can't Be Measured In Shiny Awards

I MAY DESTROY YOU, Michaela Coel’s brilliant 12-episode series released last summer on HBO (and BBC One), chronicles the haphazard recovery of millennial writer Arabella Essiedu after she survives a sexual assault. In Coel’s hands, Arabella (played by Coel herself) is never reduced to a battered woman or a perfect victim. She remains, throughout, entirely human—as do her friends and family. Watching the show reminded me of a line from Bertolt Brecht’s Messingkauf Dialogues in which an actor protests that he cannot play both “butcher and sheep.” Coel seems to disagree. Her Arabella is both warm and wildly narcissistic, armed with a righteousness that often wobbles into unbridled megalomania.

I May Destroy You is a champion of nuance. Although rape is allowed its own category of awfulness, Coel, as writer, draws her audience into other situations that aren’t so clear cut.Each episode is as compassionate as it is damning of human selfishness and myopia. Considering how little mainstream television centers the trauma and healing of Black women (much less with complexity), the critical acclaim Coel has accrued thus far is not surprising. Unfortunately, as is so often the case with art made by people of color, Black women in particular, this acclaim has yet to materialize in awards. I have mixed feelings about awards, especially when the diversity conversation in Hollywood seems in love with its own stagnancy. However, that doesn’t mean awards aren’t nice to have, or that their conferral signifies nothing; awards often reveal the white cultural establishment’s willingness to give something up. After all, if I May Destroy You gets nominated for a [insert trophy here], “Memily in Maris” might not win!

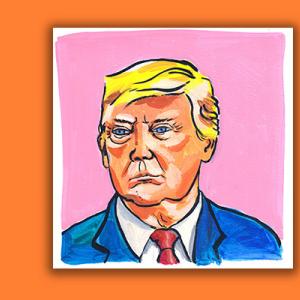

Will Trump's Portrait Orange-Wash a Disastrous Presidency?

IT'S UNLIKELY THAT Donald Trump is fretting over his presidential portrait. With further legal troubles and several industries turned against him, the man has bigger fish to fry. But as we’ve learned time and time again through the ravages of the coronavirus and police violence, just because Trump isn’t worried about something doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter. The unconfirmed, though expected, portrait offers a chance for him to shape a legacy that is in dire need of salvaging. Trump’s painting could serve to underscore—or attempt to elide—the unconventional nature of his time in office, potentially adding a glossy filter to a difficult period in American history. Of course, filtering is more than part and parcel of portraiture. It’s the very nature of the job.

Throughout the centuries, portraiture has been the province of the wealthy and, despite its biographical nature, is a genre that conceals nearly as much as it reveals. Louis XIV, another larger-than-life leader, exhibits this multiplicity of meaning all too well in his portraits. Painter Charles Poerson clothes Louis XIV in the garb of Jupiter—complete with lightning bolts in hand—to signify his victory over a series of nobility uprisings known as the Fronde. By shrouding the king’s humanity, Poerson makes Louis into someone divine, armed with greater might than mere mortals. Who needs the imago dei when you can simply be God? A different portrait replaces the gouty king’s legs with the calves of a younger man. In short, the sovereign portrait is synonymous with a kind of psychological trompe l’oeil, created to preserve power and project glory. American presidential portraits differ in their ends, though they are invested in other kinds of self-delusion: equality and equanimity.

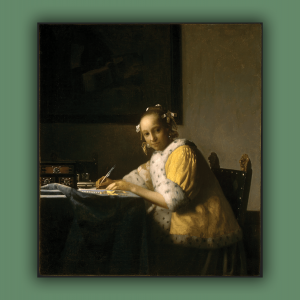

Even You Have the Right to Pontificate About Vermeer

IF YOU WOULD be so kind, I’d like for you to do an experiment with me. Think about a famous work of art, a painting so widely considered Important and Valuable its status could never be questioned. Maybe you’re debating between “The Starry Night” or “Mona Lisa.” Maybe you’re considering something else entirely: Monet’s endless assortment of water lilies, for example. Good. Hold the image in your mind and recall, if you can, the work’s textures, its colors and its moods. Do you like the piece? Do you remember when you first encountered it?

Now, having answered those questions, imagine that someone has stolen it. This mysterious person explains that they are holding the painting hostage until works falsely attributed to the artist in question are exposed as fraudulent. They sign their manifesto with the words, “You will come to agree with me.” What would that do for the public imagination?

Blue Balliett explores this question in her 2004 novel, Chasing Vermeer, and though its main characters are sleuthy sixth graders, I find its basic premise has much to offer even to jaded adults (see: me). A Vermeer painting on its way to the Art Institute of Chicago—“A Lady Writing”—disappears mid-journey, and the thief posits a series of challenges to art historians and the broader world. Petra and Calder, two intrepid University of Chicago Laboratory School students, find themselves caught in the painting’s thrall and, through a series of dreams and coincidences, set out to find the “Lady.” But they’re not alone.

What If Medusa Was Right?

IN THE GREEK mythology I was taught as a child, a recurring plot always struck me as deeply unfair. A god seduces—or rapes—a mortal woman, who either succumbs to the coercion or tries to resist. If she resists, she is punished. If she gives in, a jealous goddess punishes her.

The fact that my classmates and I had to read these myths without being encouraged to deconstruct them still disturbs me. My desire is not to sanitize art nor neuter its political incorrectness, but rather to see people (especially children) realize their agency as readers, particularly in instances where misogyny should be questioned. Which is why the installation of Luciano Garbati’s sculpture Medusa With the Head of Perseus in New York City represents a delightful inversion.

As the story goes, Medusa was a beautiful young woman, unfairly punished for being a victim of Poseidon’s lust. Because the rape takes place in Athena’s temple, Athena, believing her sanctuary defiled, turns Medusa into a monster. Medusa, now with snakes for hair, is so hideous that she can transform anyone who beholds her to stone. Perseus, a demigod himself, is tasked with killing Medusa, a duty he executes via beheading. A 16th-century bronze by Benvenuto Cellini, titled Perseus With the Head of Medusa, depicts Perseus in his moment of triumph. He holds Medusa’s head aloft while snakes emerge from her neck.

Octavia Butler and Toni Morrison Gave Us New Eyes to See

A FEW YEARS ago, an acquaintance and I found ourselves debating the value of art in a capitalist society—a suitably light topic for a summer evening. My companion believed strongly that art must explicitly denounce the world’s injustices, and if it did not, it was reinforcing exploitative systems. I, ever the aesthete, found this stance reasonably sound from a moral perspective but incredibly dubious otherwise.

Then, as now, I consider art’s greatest function to be its capacity for expanding our conceptions of reality, not simply acting as moralistic propaganda. After all, the foundational thing you learn in art history is that the first artists were mystics, healers, and spiritual interlocutors—not politicians.

We started making art, it seems, to cross the border between our world and one beyond. Prehistoric wall paintings of cows and lumpy carvings of fertility goddesses serve as the earliest indications of our species’ artistic inclinations, blurring the lines between religious ritual and art object. Even as the world crumbles around us, I am convinced we must hold onto art’s spiritual properties rather than succumbing to the allure of work that only addresses our current systems.

Why I Can't Write About Aesthetics Right Now

IF YOU EXPECT a column about art, you may have turned to the wrong page. Though I would very much like to be writing about aesthetics, I’m afraid I cannot do so outright. The problem is simple: Our world is on fire, has been for a very long time, and we can no longer afford to avoid the why. Our country looks in the mirror and cannot recognize its face because its self-concept is built on lies. To be an American, it seems, is to be in a state of constant dissociation. Perhaps that is the fine print in our social contract—mandated distance from our inner worlds and the violence we inflict on each other.

But, if we are constantly looking away from ourselves, what are we looking at instead? The answer is, again, simple. We—this “we” primarily composed of white people—have traded a clear vision of reality away for the tawdry allure of images. Put frankly, we worship a portrait of America that has not yet come into being.

Fiona Apple: Patron Saint of Prophetic Women

FIONA APPLE’S 2020 internet takeover began the moment she released her newest album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, in April. This cyber movement was not orchestrated by Apple, who does not have any social media accounts, but rather by the countless women tweeting, Instagramming, and exulting over the album. I probably have the algorithm to thank for the prevalence of these posts in my feed, as they were mostly from my demographic—millennial women with overflowing collections of books and high-waisted pants. Yet, algorithm or no, the joy I witnessed was completely organic, and if you’ve heard the album, you’ll understand why.

Many people’s introduction to Fiona Apple is not her strong, eclectic body of work. Instead, it’s her infamous speech at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards in which she exhorts viewers, especially adolescents, not to model their lives after “what we think is cool.” After that, Apple seemed to vanish from the public eye, emerging every so often with an absurdly long album title that tied bundles of complicated songs together.

I’m beating around the bush with the word “complicated.” What I really mean is “angry.” Fiona Apple is one of the few women in music who is allowed to be furious in an unpretty way. She has become a secular patron saint for prophetic women whose insight makes them vulnerable to the ridicule of others.

The Trouble With the Word ‘Curated’

CONFESSION: I HAVE a bone to pick with the word “curated” this month. I’m finding that the word, while generally useful in art contexts, let me down during Lent this year.

Let me explain.

“Curation” evolved from the word “curare” (to take care of) but, as it exists now, covers anything from making playlists to putting on a painting exhibition. I don’t have an issue with the chameleonic nature of the term, though I know it’s beginning to vex actual museum curators. What is difficult for me to wrap my mind around is the fussiness that curation implies.

It’s synonymous with caring for objects and, subsequently, caring for an audience by displaying the objects in an interesting and informative way. But, as a representation of spiritual wilderness, Lent seems diametrically opposed to the idea of a carefully considered experience. In Lent, nothing is planned. This year, I simply showed up in the metaphorical desert and started walking.

More People of Color Are Protecting Art Than Curating It

A FEW MONTHS ago, I found myself in a familiar position: at a museum, taking selfies with an artwork, which, in my defense, was made of mirrored surfaces in the shape of Queen Elizabeth II’s face. The opportunity was too good to resist. There I was, snapping away, long coat and checkered socks coordinating with a print near me that read, “Empire buying begins at home.” That’s when I heard disgruntled murmurs.

I pretended to photograph more art, all the while inching closer to the source—museum security guards. I listened to them commiserate over their low pay and meager benefits compared to salaried employees, and the unfairness of hourly wages in the case of emergency museum closings. I completely agreed with them.

Since my introduction to art museums, it’s become increasingly clear that the values many tout (equity, multiculturalism, and inclusion, for example) are far too vulnerable to the wiles of capital, capital, and capital. Not only is there a problem with wage and benefit gaps, there’s an interesting breakdown of who works in museums and what positions they hold. I remember my first visit to the Art Institute of Chicago: I was an awed high school freshman racing down hallways with my friends, trying to complete an educational scavenger hunt. I did well, but that’s in part because my teachers didn’t ask me to find a person of color who wasn’t a security guard.

Dear Friend, This Is a Human Moment

Dear friend,

It was quite a year, wasn’t it? Some might say 2019 was grim: I wish I could disagree. I wish I could offer artwork to capture the world’s ills, move us to radical change, or even get us to be kinder to our neighbors. Unfortunately, there is no one piece existing on these terms.

Instead, I will tell you something I witnessed in 2019, hope and wonder that I tucked into my coat pocket because it reminded me of what the Kenyan filmmaker Likarion Wainaina said: “I want to make work that makes people more human.”

The following, my friend, is a human moment.

In October I attended a deeply moving talk at the Yale Center for British Art. Hilton Als, theater critic for The New Yorker and occasional curator, spoke about Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s work and what it means to him. Yiadom-Boakye is a British-Ghanaian painter creating transcendent worlds with her brushes. The results are beautiful images of black people plucked from her imagination, combined with Western canonical influences—particularly Johannes Vermeer’s interiority and Alice Neel’s frankness. In his engagement with her style, Als toggled assuredly between philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, writer Jamaica Kincaid, artist J.M.W. Turner, and others.

Being Amazed in an Anxious City

A YOUNG WOMAN armored in her blazer, caffeinated and tethered to the phone line of a Manhattan hedge fund, hardly seems the optimal audience for an artist whose work hinges on stillness and contemplation. And yet—if you saw an enormous book of James Turrell’s installations perched on your desk, how could you not open it?

That was my reasoning as I re-encountered Turrell’s oeuvre, third cappuccino in hand. I didn’t know it then, but Turrell’s artistic framework would provide a new way to think about New York City. More specifically, his clarity of vision vis-à-vis light and space stands in contrast to a city replete with people the critic John Berger describes as “resigned to being betrayed daily by their own hopes.”

The city that allegedly never sleeps is wonderful in many ways, but by the end of my tenure there I was increasingly overwhelmed by the hustle, noise, and collective anxiety around, well, everything. Temping at a capital investment firm, while a welcome paycheck, was not my idea of meaningful work, and sitting like a bird in a glass tower, detached from the people below, even less so. Reaching for Turrell’s book, which was likely deemed politically neutral enough for an office setting, was an act of desperation and belief that I could still be surprised, awed even. And I was.

Myth and Meritocracy

In his seminal work Mythologies, French philosopher and critical theorist Roland Barthes announces that “Myth is a type of speech.” And not simply any type of speech, but a dangerous kind. Myth is problematic, he says, because it allows a fictional brand of naturalism to subsume history. It creates a false narrative that the way things are is the way things are meant to be, leaving ample room for injustice to flourish.

Recently, the playwright Jeremy O. Harris tackled one particular section of American mythos: education. And, in typical Jeremy O. Harris fashion, his exploration is complicated.

I went to see Harris’ fantastical play “Yell: A ‘Documentary’ of My Time Here” in a state of fear and excitement, wondering what dirty laundry he would air about my then-future intellectual home.

The Point of Art

“ARTISTS EXPRESS things that people don’t have words for; that’s why it’s so important to have them in justice spaces.”

With that neat answer, the panelist sits back in her chair, satisfied, bedazzled nails glimmering in the stage lights. I roll my eyes, then immediately feel guilty. You know you’re in for a rough night when you find yourself side-eyeing a Tony Award-winning actress—at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day event, no less—but I can’t help myself. Her answer smacks of the vague, self-congratulatory art-speak I hear on a regular basis, in which people tell me their work is a “metaphor for capitalism,” without any kind of explanation.

The Art of Transcendence

IN THE SPAN OF OUR HOUR-LONG conversation, Mimi Mutesa, an emerging Ugandan-American photographer-videographer and an undergraduate student at Calvin College, a Christian Reformed school in Michigan, easily gives her thoughts on everything from the complexities of blackness to the policing of women’s bodies. However, when I ask her how her faith influences her work, there is a brief pause on the other end of the line.

“I don’t think it’s ever crossed my mind until this moment,” she says. When pressed, she explains that she’s “trying to tackle enough issues” in her art as it is, and evangelical culture has “far too many other problems” for her to address. Mutesa assures me that she still identifies as a person of faith but maintains that her relationship with God is “separate” from her relationship to art and social justice.

Perhaps this separation is a necessary one. It’s hard to imagine the average evangelical church embracing Mutesa’s colorful portraits of nude black joy. Her sentiments echo an unspoken opinion held by many young Christians, that if you want to be radical like Jesus was, you must do so on the margins of Christianity. More traditional folks may see this rush to the margins as a slick avoidance of the Christian call to profess one’s faith, or a symptom of postmodern discomfort with absolute truth. But what is more likely is that millennials of faith, especially millennials of color, want to engage with values traditionally cherished by the church but see modern-day Christianity as a direct hindrance to that sort of exploration, since significant portions of the church have been antagonists in struggles for social equality.

Reticence to conflate personal faith with artistic vision is deeply connected to a complex historical dialectic between the arts and the church: Mutesa’s midconversational pause is supported by precedent.