Jenna Barnett (@jennacbarnett) is the senior associate culture editor at Sojourners and the host of the audio limited series Lead Us Not. She was born in San Antonio and lives in San Diego. She has a B.A. in sociology and religion from Furman University and an M.F.A in Literary Reportage from New York University.

Before joining the Sojo team, Jenna managed the International Rescue Committee’s urban gardens in San Diego, and worked as a writer for the Women PeaceMakers Program at the Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice.

She has written for McSweeney’s, Texas Monthly, the Belladonna, and New York Magazine’s Grub Street. You’re likely to find her playing basketball, watching women’s soccer, eating homemade flour tortillas, or taking her time in Scrabble.

Some Sojourners articles by Jenna Barnett:

Culture:

Brandi Carlile’s Radical Gospel of Gentleness

“What I'm talking about is radical, filthy, trembling, scary, life-changing, beautiful forgiveness,” the Grammy-winner told Sojourners in an interview.

Snorting Nutmeg at Vacation Bible School with Lucy Dacus

Her album Home Video could have just as easily been named “Youth Group” or maybe “Adventures in Suburbia.”

Features:

How Do We Recover When Our Leaders Betray Us?

Charismatic leaders like Jean Vanier can inspire our faith — or make it fall apart.

Let There Be Light

When sexual abuse occurred in their church, Rev. Heidi Hankel and her congregation refused to let it stay hidden.

Humor:

Footprints in the Sand (Unedited)

Lord, when I needed you most, why were you snacking on Flamin' Hot Cheetos?

John the Baptist’s Recipe for Honey-Crisped Locusts

Once the locusts are as hot as a wealthy hypocrite burning in hell (about 200 degrees), add the honey.

Posts By This Author

Womanhood and Parenting in the Black Lives Matter Movement

A web-exclusive interview with Erika Totten

Short Takes: Erika Totten

Bio: Erika Totten is a leader in the Black Lives Matter movement in Washington, D.C., and the black liberation movement at large. She is a former high school English literature teacher, a wife, a stay-at-home mom, and an advocate for the radical healing and self-care of black people through “emotional emancipation circles.”

1. How did you get started with “emotional emancipation” work?

Emotional emancipation circles were created in partnership with The Association of Black Psychologists and the Community Healing Network. I was blessed to be one of the first people trained in D.C. I had been doing this work before I knew what it was called. My organization is called “Unchained.” It is liberation work—psychologically, mentally, spiritually, and emotionally.

I want to tell people to be intentional about self-care. Recently, we had a black trans teen, who was an activist, commit suicide. A lot of times you need to see a counselor or therapist, which is often shunned in the black community. Because of racism, we are taught that we need to be “strong.” But it’s costing us our lives. As much as we are dismantling systems, we have to dismantle anything within ourselves that is keeping us from experiencing liberation right now.

School of Love

WHEN FATHER THOMAS PHILIPPE brought philosopher Jean Vanier on a tour of asylums, institutions, and psychiatric hospitals, Vanier discovered “a whole new world of marginalized people ... hidden away far from the rest of society, so that nobody could be reminded of their existence.” A year after this realization, recounted in The Heart of L’Arche, Vanier founded the first L’Arche community in his new home in France. Vanier shared meals, celebrations, and grievances with Raphael Simi and Philippe Seux, two men who had lived in asylums ever since their parents passed away.

Vanier was inspired by life with these friends, and motivated by a new understanding of Luke 14:12-14: “‘When you give a luncheon or a dinner, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your relatives or rich neighbors, in case they may invite you in return, and you would be repaid. But when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind. And you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you, for you will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous.’”

In the words of Vanier, “L’Arche is a school of love.” It is a “family created and sustained by God,” and it is an embodiment of the belief that “each person is unique, precious, and sacred.” In practice, L’Arche is a global network of communities: People living with and without developmental disabilities sharing meals, prayers, work, and advocacy efforts.

10 Artists of the Black Lives Matter Movement

While statistics, tweets, marches, and articles can bolster and enliven movements, art brings in the endurance. Art makes injustice a song that gets stuck in your head. Art makes murals out of obituaries, and hope out of statistics. Below, check out some of the art surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement:

1. Epitaph as protest. In “All Eyes Are Upon Us” (Sojourners April 2015) Gene Grabiner references 14 fallen people of color—men, women, and children, from 1973 to 2014—all casualties of “this war against the people.”

2. Nightmares. In her spoken word poem “black. anathema.”Jessica Edwards mourns the feared death of her unborn black child: “My soul mourning you prematurely, / clutching my empty womb bitterly.”

'This Is How We Fight Terrorism:' Syria's Sacred Music

The destruction and looting of art and historical sites in Syria is "the worst cultural disaster since the Second World War,” according to anthropologist Brian L. Daniels.

The human losses are devastating: At least 210,000 people have died in the ongoing battle between the Assad regime and the Syrian rebels. ISIS has joined the violence and exploited the instability in the country, taking control of large parts of northern and eastern Syria.

And now, in the unofficial war over Syria’s cultural heritage, art is the main casualty. As of September 2014, five out of six of Syria’s Word Heritage sites had been destroyed including Aleppo’s 12th century Umayyad mosque.

ISIS’ ruthless participation in the Syrian conflict only increases the danger to Syrian art and history: In ISIS controlled Mosul, Iraq, art, music, and history have been removed from school curriculum. In February, ISIS released a video of its fighters smashing ancient statues and artifacts in the Mosul museum in an effort to weed out “heresy,” prompting the UNESCO Director-General to call for an emergency meeting with the Security Council to advocate for the “protection of Iraq’s cultural heritage as an integral element for the country’s security.”

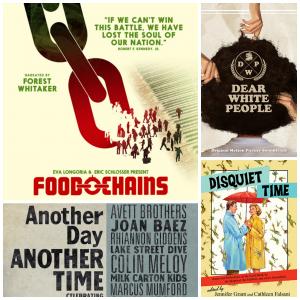

New & Noteworthy

Going it Alone

Reclaiming 'Angry' Feminism and Other Lessons from 'She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry'

Bras weren’t the only things the second-wave feminists burned in the ‘60s. But that’s all I learned about the movement in school and casual conversation (on the rare occasions when feminist movements were brought up). The documentary, She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, fills in what our education system and historical imaginations leave out.

Second-wave feminists also burned oppressive patriarchy, definitions of feminine beauty, and, most poignant to me, their hard-earned diplomas. They literally set fire to bachelors degrees, masters degrees, and PhD certificates. An activist in the film explained, "We had graduated and learned nothing about women."

This documentary shows us what the textbooks didn’t and still don’t show often enough — the early, angry, undoubtedly beautiful grassroots radicals.

Of course, not all anger is beautiful. Some anger is abusive, relentless, and uncontrollable. I noticed three types of anger in the documentary — one beautiful, and two problematic.

Saints and Nomads

MARILYNNE ROBINSON’S Lila is the love story we thought we already knew, but didn’t. Lila takes us back to Gilead, Iowa, the same setting as Robinson’s novels Gilead and Home, describing the backstory and courtship of old Rev. Ames and the much younger Lila from a completely new point of view.

In Gilead, Ames describes his immediate, unlikely love for Lila, the hard-working wanderer. But Ames’ description of the feeling of love is more vivid than his description of the woman he loves.

The reverse is true in Lila. We learn Lila’s story through thick third-person prose. Robinson’s narration often reflects Lila’s stream of consciousness—a scattered, questioning pattern of thought, apt for a woman digesting the idea of small-town permanency after an exciting, scary, shame-filled life on the road. In the novel’s opening scene, Lila is just a small child, neglected and dying on the front steps of her house. Doll, a loving and hardened itinerant, kidnaps her just in time. It’s unclear if Doll stole or saved Lila. We can’t ever be sure. Either way, her love for Lila is fierce, and Lila comes to depend on it as they travel around the country, living off of door-to-door labor and inside jokes.

TIMELINE: LGBT People and the Recent Church

A timeline on the church concerning the LGBT community

The Torture Report: A Historical Perspective

The release of a 600-page executive summary of the CIA torture report on Tuesday gave confirmation and imagery to many of our saddest suspicions and vague understandings of the CIA’s use of torture. The report, conducted by the Senate Intelligence Committee between 2009 and 2013, reveals that the U.S. carried out post-9/11 “enhanced interrogation techniques” in an ineffective and fear-fueled effort to prevent terrorism. In an attempt to protect our nation, we lost our values, and then tried to destroy the evidence. Still, many shameful specifics are now public knowledge:

Interrogators have exposed detainees to dark, cold isolation, forced rectal feedings, threats to family members, simulated drowning, 180 hours of sleep deprivation, and much more. The Justice Department still hasn’t pressed any federal charges.

This government transparency is new, but the sins are old. Sojourners has advocated for the end and exposure of U.S. torture techniques for years. Take a look at the Sojourners articles below to learn more about the effects of the program and the dreary history that precipitated the report.

Four Questions for Beth Katz

Beth Latz is founder and executive director of Project Interfaith, projectinterfaith.org

1. Why did you decide to launch Project Interfaith?

There are a couple experiences in my life that led me to found PI. One would be that my grandparents immigrated to this country after experiencing harsh persecution as a result of their Jewish identity. Another would be growing up as a religious and ethnic minority and encountering a lot of people making assumptions about what that means. I didn’t always feel welcome or free to be who I am. But growing up and hearing about my grandparents’ experiences in other countries, I realized how lucky we are to have certain rights in this country. So I wanted to make sure people understand these rights and freedoms.

New & Noteworthy

Truth and Satire

The witty film satire Dear White People is a comic entry point into a serious, much-needed conversation about race relations on college campuses. The storylines of four African-American students at a prestigious university spotlight a culture of racism that is easily and dangerously concealed by academia’s progressive posture. dearwhitepeoplemovie.com

The Most Affirming Sanctuary of My Life (So Far)

Editor's Note: In this new series, we explore the ongoing conversation within the church over LGBT identities, affirmation, and inclusion. As the push for equality expands, how are communities of faith participating and responding — and is it enough? We will be examining this at a deeper level in the January issue of Sojourners magazine, with a cover story from evangelical ethicist David Gushee. Subscribe Now to receive that issue.

During the opening worship service at the Reformation Project’s Washington, D.C., conference, a weekend of events promoting the biblical affirmation of the LGBT community, something seemed amiss. I looked around the church pews to find what fueled my unease. Maybe it was the guitar-charged praise music alongside traditional liturgy. Or maybe it was the older white man listening intently to the younger gay black woman. Evangelical vibrato next to mainline rigidity, old next to young, white next to black, gay next to straight next to bi next to transgendered.

It was a Galatians 3 kind of room — a reminder that in Jesus there is no longer “Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female.” Gay or straight.

“For all of you are one in Christ Jesus.”

It was that sacred “oneness” that surprised me. Nothing was actually amiss — all things were new. There was a colorful rareness and a refreshing affirmation.

Rev. Allyson Robinson gave the opening address of the conference, offering prayer, Scripture, encouragement, and a few warnings for the LGBT-affirming church. The warnings came in the form of analogy in which she likened the temptations of Jesus in the desert to the temptations of the affirming church on the verge of a culture war victory.

STORYMAP: 5 Game-Changing Aid Groups

A map depicting five quality aid groups nationally and abroad

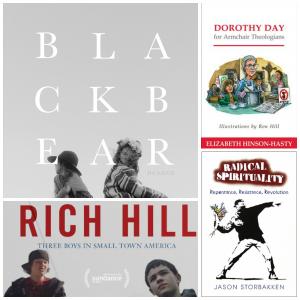

New & Noteworthy

Calling to the Deep

In Radical Spirituality: Repentance, Resistance, Revolution, Jason Storbakken, co-founder with his wife, Vonetta, of the Radical Living Christian community in Brooklyn, N.Y., fluidly weaves scripture work with political critique and his own fascinating history in this call to find deeper life in Christ found on the margins. Orbis

VIDEO: A Dream Deferred in Ferguson

Ryan Herring reads Langston Hughes' "Harlem" as photos of Ferguson are displayed.

5 Pop Culture Jesuses

The Jesus of pop culture is multiethnic and well-traveled, pious and irreverent, singing and silent. A fictional portrayal that is blasphemy to one viewer is sacred to another. The diversity of Jesus’ depictions reflects the diversity of the pop culture audience. Most recently, another fictional Jesus has appeared in Compton, smoking weed and promoting “black-Latin” reconciliation in the new comedy Black Jesus. The sitcom presents a Jesus who uses at times crude language to ultimately promote a consistent gospel message of love. While this Jesus “shares in the pleasures” of his largely poor, African-American community, “he also challenges their prejudices, violence, and self-seeking.” Read more in Danny Duncan Collum’s “The Christ of Compton” (Sojourners, November 2014).

Check out this list to read about five portrayals of Jesus in recent pop culture history.

1. Lion Jesus

In The Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis sets up a less than subtle allegory of Jesus in the form of a lion named Aslan. Aslan transforms a void into a world through song. He welcomes children. He dies and comes back to life. But still, he is a lion, fierce and elusive, helping to convey both the intimidating power and the radical love of Jesus.

“‘Safe?’ said Mr. Beaver; ‘don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course [Aslan] isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.’” –The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe (1950)

Make Way for the Female Antihero: TV Takes a Page from the Bible

These days, female television characters can almost do it all. But we, the media consumers and producers, are still deciding if we should let them make mistakes, too.

And I don’t mean just the I-dated-the-wrong-handsome-doctor mistakes, or the I’m-an-overprotective-mother mistakes. I mean the type of mistakes that warrant the label of antihero. Merriam-Webster defines an antihero as “a protagonist or notable figure who is conspicuously lacking in heroic qualities.” Over the past several years, TV has become saturated with male antiheroes. Breaking Bad made a meth dealer Emmy gold, and Dexter garnered a cult following behind a sociopathic vigilante. But hey, boys will be boys.

Girls will be girls, too, if we let them. And girls aren’t always perfect. John Landgraf, president of FX, says it’s much harder to find acceptance for the female antihero: “It's fascinating to me that we just have really different, and I think, a more rigorous set of standards for female characters than we do for male characters in this society.”