Kathy Khang, a columnist for Sojourners magazine, is the author of Raise Your Voice (InterVarsity Press, 2018) and co-author of More Than Serving Tea (InterVarsity Press, 2006). She blogs at www.kathykhang.com, tweets and Instagrams as @mskathykhang, posts at www.facebook.com/kathykhangauthor, and partners with other writers, pastors, and Christian leaders to highlight and move the conversation forward on issues of race, ethnicity, and gender within the church. Kathy also has worked for the past 19 years with a national parachurch organization.

Posts By This Author

What About Fires Closer to Home?

JUST WEEKS before the fire, I was in front of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, walking around the exterior and enjoying the architecture and ornate sculptures depicting stories of the Christian faith. I didn’t go inside, and I may never have the chance because of how long it will take to rebuild Notre Dame. The iconic wooden spire and roof are gone, as experts try to assess how to support the remaining structure and make it safe. There is international support and money to rebuild, because it appears a tragic accident has destroyed a place that is considered sacred even to those who consider themselves secular.

And that is why so many of us should keep going back to why the burning of three black churches in Louisiana didn’t fill 24-hour news cycles or make us—me—stop and turn on the news.

Desperate for a Spiritual Spring

I DON'T SET New Year’s resolutions. Jan. 1 is always either too early or too late for me to predict or dream about what is new. Those seeds are planted in the fall with tulip and daffodil bulbs and cool-weather crops, or in the spring with the vegetable gardens and annuals.

Where I am in the Midwest, the church calendar is coinciding with nature. As I write this, the temperature is hovering just above zero degrees Fahrenheit, with wind chills dipping close to 50 below zero. People die in this sort of weather; newscasters are reminding their viewers to call loved ones and neighbors to make sure they have heat and are staying out of the elements.

While fall is my favorite season and winter contains Christmas, I need spring. It’s when the roots of ferns and other perennials seemingly dead under the frozen earth, the buds on branches that have managed to stay connected to the trunk despite ice, and my heart weighed down by depression and seasonal affective disorder desperately start to crawl out of the layers to find air, sun, and warmth. I am desperate for a spiritual spring.

The Price of the Church’s Assimilation

I SPENT MOST of my childhood in a Methodist church, but I didn’t learn the liturgy. It was sung in Korean, and as soon as I started kindergarten, I exchanged fluency in my original language for assimilation. My parents did their best to teach my sister and me as much about our language and customs as they could, but they had to teach us in between their own assimilation for survival. It wasn’t until years later, when I was on a campus ministry team that sang from hymnals and overhead projectors, that I connected the Korean words of my church upbringing with a Korean-American faith.

As I’ve begun working through the personal cost of assimilation, I’ve looked at the price the church is paying for its own assimilation. At the sound of that, you may think that the rest of this column focuses on legalized abortion, same-sex marriage, and maybe even immigration and border security. Well, it does and it doesn’t.

I wonder if white evangelicalism has thought of itself as the underdog, the persecuted, and the eventual white savior in order to assimilate into a Western culture that glorifies winning, beating all odds, and rising as the unexpected hero. How can this country simultaneously be a Christian nation and persecute Christians? Neither is accurate, but both claims are invoked in modern politics and the rhetoric of white evangelicalism—where white evangelicals assimilate into a blind patriotism that ignores history and orthodoxy.

Dear White Santa (the sequel)...

I'M TOO OLD, and so are my children, to set out cookies and milk for you. But I’m still hopeful enough to write you another letter.

Last year, with all the earnestness I could muster, I asked you for a white people intervention—many white progressive and evangelical Christians in the same room for a cleansing flood of white tears, some deep breathing and healing prayer, and time to plan to dismantle white supremacy from the inside.

But I have not received word that an intervention took place. I assume invitations to it went out or it got canceled, postponed, or taken over by the announcement of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy’s retirement. (Was that supposed to be a Christmas-in-summer gift?)

On Leaving Our Church of Two Decades

I DID NOT leave my church on a whim.

It actually took me and my spouse two years to slowly rip the bandage off and leave. After more than a decade of sitting on the left side of the sanctuary, serving on the worship team, starting a drama group, learning the language of the denomination and congregation, pricing countless items at the annual rummage sale, and teaching confirmands, we decided it wasn’t the church. It was us.

It wasn’t about what was said or wasn’t said on a single Sunday after yet another national tragedy or shocking event. It wasn’t one sermon or one congregational prayer. It was a long silence over years—silence from the pulpit, silence from the hymns and contemporary love songs to Jesus and God, silence from the congregation even when the denomination tried to make a sound, silence as #BlackLivesMatter trended, silence after #Charleston.

The silence was so loud, it almost drowned out the painful words that were spoken. They attempted to diminish and ignore the pain that was real for us and our family, week after week, month after month, year after year. We were asked to bring a dish for the cultural potluck, but not too much, so our feelings wouldn’t be hurt if people didn’t like what we brought.

Finding 'Voice'

I USED TO BE in the business of making moving and packaging supplies, as well as kindling.

Yes, I was a newspaper reporter. The demise of print news has been alleged for decades, and though I no longer am a newspaper reporter, I still turn to my pile of semi-read news to help me the start the occasional fire.

I’m not sure what category book authoring falls under, but it certainly feels riskier than print news. Perhaps that’s why it took me so long to drum up the courage and time to put it all down. A newspaper story has a shelf life of about 12 to 48 hours, depending on the news cycle, and then it can literally be recycled. These days—with Twitter and a thumb-happy resident in a famous white house—it seems the news cycles even faster. Critique of digital news can be brutal, but it’s also fast. A book takes much more time to read, never mind the time it takes to write, and one of my fears is that time opens up space for critique.

Keeping the Faith in Trump's America

Jmaggiophoto / Shutterstock.com

"In the wake of this election, the role of faith communities is imperative," writes Jim Wallis in "Resistance and Healing." With this in mind, we asked a few Christian leaders how followers of Jesus can best practice resistance and healing in Trump's America. Though varied, the responses we received have a common theme: Christians must stand in solidarity with the vulnerable. Now and always. —The Editors

Resistance is Holy Work

by Brittany Packnett

RESISTANCE IS HOLY WORK. Resistance is what it means to tell the truth and defend people in public, even—and especially—when it is inconvenient, dangerous, and uncomfortable.

What truths must we tell? We must tell the truth that the entire world is not white, straight, Christian, cis-gendered, American-born, male, or able-bodied, and that those of us who aren’t matter just as much as those of us who are. We must tell the truth that rhetoric and policies that encourage violence against those same people is not of God and not of the freedom we espouse. We must tell the truth that if all of us were truly created equal, then the cancer of xenophobia makes all of us sick—and that none of us are truly free until we are all free.

We did not lose an election as much as we validated and normalized a way of life that is beneath our humanity—and, therefore, which requires our resistance. The Christ I serve did not sit idly by in times like these—for in eras like this one, inaction is a sin. Inaction perpetuates this latest wave of hate just as much as if you painted a swastika yourself. Hate should never be welcome in our homes, at our tables, in our worship, or in our country.

It is holy to resist such things. Holy resistance means calling out that hate by name and casting it out of where you are—of where you want God to be. Casting it out means no longer making excuses that your grandfather just talks like that because he is elderly; it means withholding your tithes and membership from those places that will not be safe havens and sanctuaries for those persecuted under potential new rules of law; it means challenging the notion that we stitch together a false unity rather than acknowledge the explicit danger many of us are now placed in.

Holy resistance means praying for those who persecute—but protecting the persecuted. Christians must be people of moral conscience, those who conscientiously object to hatred, division, racism, and sexism as unashamedly as we claim Christ. The call to be in the world and not of it was for such a time as this—we must be the light that shines on injustice and calls out our humanity to replace the evil we see.

Resistance is holy work. That makes it our work.

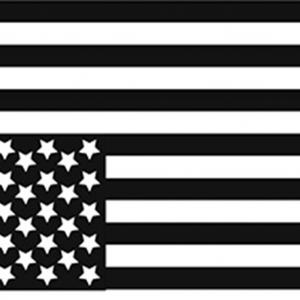

Distress Signal

The flag should never be displayed with the union down, except as a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property.

—U.S. Flag Code

IT SEEMS RATHER odd that a normal part of my catching-up-at-the-end-of-the-day conversation with my partner is discussing the whiplash of political events. Leaks are not conversations about the sink. Notes are not to be turned into the teacher. Tapes are not our latest vintage find. They are all political subjects and part of the ever-evolving new normal. And just as spring was forcing its way into bloom, it was announced that Officer Betty Shelby of the Tulsa (Okla.) Police Dept. was found not guilty of first- degree manslaughter in the shooting death of unarmed Terence Crutcher.

More than a New Group of Friends

THERE IS THIS unsightly patch of spider veins behind my right knee. It started out years ago after my body had carried to term the weight of three pregnancies and endured the recovery associated with childbirth. A little spider vein turned into a few, which turned into a patch that eventually went from simply visually unappealing into painful and bulging.

I had hoped an injection would take care of both the pain and the patch of blues and greens. However, after closer examination via ultrasound, I learned that a larger vein, which to my untrained eye had nothing to do with that painful patch, was actually the key to treatment. We couldn’t start on the surface. We had to dive deeper.

Now there’s an analogy.

It hasn’t been enough for the church in the United States to talk about racism and sexism. Building relationships across racial divides is good, but it isn’t enough. Your new black, white, Asian, Latino, or Native friend doesn’t give you a pass. Sure, it’s a great photo op or church story, but deep down inside it will take more than everyone making a new group of friends.

It hasn’t been enough to talk about unity without addressing the cost of uniformity. It hasn’t been enough to research the most segregated hour of the week and then quote Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. The unsightly and painful patch of damaged veins goes much deeper and requires far more than a single injection. The brokenness of the church requires surgery—amputation, transplant, transfusion, or a combination of all of the above. The healing of the church requires a Jesus that is not dressed in Sunday best because there never was such a thing.

Opting Out of the Black-White Binary

Ongala / Shutterstock

THE CIVIL RIGHTS movement. #BlackLivesMatter. Racial reconciliation. It would be easy for me to imagine the words of Eliza in the musical “Hamilton” and sing, “I’m erasing myself from the narrative.”

At first glance, those statements, movements, and conversations might be mistakenly boiled down to division and brokenness between two Americas—one black, one white.

But I’m neither. I’m “yellow.”

I didn’t choose to erase myself in history, but it’s what I learned. Asian Americans weren’t erased from American history as much as we just didn’t exist in the Plymouth Rock story of East Coast immigration, with its emphasis on Europe’s poor and hungry “huddled masses.” We learned that “assimilation” was as much about becoming “white” as it was about becoming “American.” We learned that the civil rights movement was a fight for equal rights for black Americans, with little connection to “others” like myself. There was no category for someone who looked like me unless it was Oriental, chink, or gook—racial slurs I first heard as a child on suburban playgrounds (and still hear as an adult), slurs tied to a history and wars I knew very little about. In America, race is a social construct divided most simply between black and white.

I also learned that the best I could hope for was to become a model minority, an “honorary white” who would never be considered a “real” American.

So I just didn’t become one. In an act of rebellion, I chose not to become a naturalized U.S. citizen until a few years ago. In the process I learned what it means to opt into a binary conversation with a different, clear, defined perspective. I needed to learn who I was, created as a Korean-American woman carrying God’s image. I needed to learn that Jesus, Mary, Martha, and Esther weren’t blue-eyed or blonde.

Easter People in a Good Friday World

The Irony of 'Craftivism'

MY MEDIUM OF choice is usually words. My activism often takes the shape of a column, sermon, or talk, a march or protest, lobbying representatives, attending meetings “to be a voice,” and voting. But recently, I took on activism with a needle and went back to a hobby of mine to bring my words to life: cross-stitching.

Through the miracle of social media, I was connected to Alicia Watkins—who offers back-stitched pithy sayings, and images of microbes, through her Etsy shop, including a pattern to stitch “Nevertheless, she persisted” on a tiny piece of fabric. Tiny stitches formed the letters and communicated what many women across the globe do, through a type of art form that is often disparaged as “women’s work.” Watkins and I are not alone. Shannon Downey of Chicago calls the activity “craftivism,” and through it she raised more than $5,000 in November 2016 to combat gun violence.

The irony is not lost on me. It’s actually what I love about needlework. Textile art, embroidery, sewing, darning—across time and space they have been women’s work, girls’ work, the work of the poor. Nowadays we can sell the work online and get paid through PayPal, never actually connecting in real life, not even through a middle-person. But I was taught to sew because clothes and socks were not as disposable as they are now, 40 years later.

Dear White Santa

NOW THAT WE can say “Merry Christmas” again (Did we forget to thank you for this? Thanks. No, really. Thanks a lot.), I wanted to cut to the chase with my wish list this year. It’s short.

I would like a white people intervention. Please get as many white Christians—progressive and evangelical—in the same room for a cleansing flood of white tears, some deep breathing and healing prayer, and time to plan to dismantle white supremacy. As just one of several million Asian Americans, I can only do so much to keep educating white people about the system their ancestors—who did or did not enslave people or benefit from slavery (by the way, all Americans who aren’t African American benefitted from the evil of slavery)—created and continued to adapt and adopt.

When We Expect Too Little of the Church

SOME PEOPLE SEEM to relish being described as “prophetic voices.” I’ve never enjoyed being called that. Old Testament prophets seem rather lonely and cranky, and, despite some of the things I write, I am not cranky after I have my coffee.

I wanted to write this column with more levity, more joy, and more hope. My first upbeat draft didn’t feel quite right, a bit forced, but I submitted it—trying to honor the deadline and ignoring my gut that was telling me the words didn’t match my heart.

Hours later, white supremacists marched at the University of Virginia carrying Tiki torches and shouting Nazi slogans.

3 Steps to Repairing Community

Image via Wes Dickinson/Flickr

Repairing isn’t as easy as it sounds. It’s rarely as straightforward as we hope for. And sometimes it’s downright costly, or worse, impossible. If the church wants to be a part of repairing entire communities, we need to be willing to do at least three things: Gather the experts, put in the time, and give and live sacrificially.

The Woman Who Spoke When Jesus Was Silent

Sometimes there are no advocates, no allies, no other choices but to be the one to take a risk with no guarantee or promise of success, of justice, of healing.

In Times of Dire Distress

Maybe I am the only one wondering “What can I do?” as I watch and read the news of demonstrations throughout the country. I have a lot of excuses. I can’t go to the protests tonight because my son has a concert. I don’t coordinate the church service and announcements, so I can’t control what will and won’t be said. I’m on sabbatical so I won’t be a part of the conversations that I hope will happen between colleagues at meetings. But I hope I am not the only one wondering what can be, needs to be, ought to be done.

The videos are chilling – Eric Garner’s life is being choked out of him until he goes limp on the sidewalk and Tamir Rice is being gunned down, the police squad door barely opening as the officer drives by. The images of protests and protesters being tear gassed and throwing canisters back at police armed in riot gear remind me of the summer I spent in Korea, marching in protests against U.S. military presence. That was the summer I learned about wearing damp handkerchiefs near my eyes and over my nose to help with the sting of tear gas and how to wet the wick of a homemade Molotov cocktail before lighting and lobbing. A few years later in a hotel room in Indiana after a job interview, I watched protests and riots take over Los Angeles. Living with, wrestling with injustice day in and day out is a bit like a kettle of water just about to hit boiling. At some point, the water boils, the steam is released.

An Open Letter to the Evangelical Church: I Am Not Your Punch Line

There are few things as exhausting, draining, and disheartening as family drama. I’m not talking low-level sibling rivalry over who gets shotgun all the time. I’m talking deep-rooted family issues that go generations back. That kind of family drama shows up in the most inopportune times in the most inappropriate places — at someone’s wedding or funeral, at the family reunion, or while grocery shopping.

But when family drama shows up in the church, it grieves me. It riles me up like nothing else does because it is in my identity as a Christian and Jesus-follower where I am all of who God created me to be and has called me to be — Asian and American, Korean, female, friend, daughter, wife, mother, sister, aunt, writer, manager, advocate, activist. The church is the place where I and everyone else SHOULD be able to get real and raw and honest to work out the kinks and twists, to name the places of pain and hurt, and to find both healing and full restoration and redemption.

So when the church uses bits and pieces of “my” culture — the way my parents speak English (or the way majority culture people interpret the way my parents speak English) or the way I look (or the way the majority culture would reproduce what they think I look like) – for laughs and giggles, it’s not simply a weak attempt at humor. It’s wrong. It’s hurtful. It’s not honoring. It can start out as “an honest mistake” with “good intentions,” but ignored, it can lead to sin.

Fortunately, there is room for mistakes, apologies, dialogue, learning, and forgiveness.

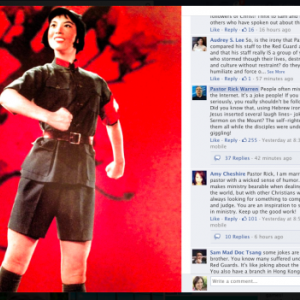

I Emailed Pastor Rick Warren and There Is No 'If'

So, here is the dilemma. Do I think so highly of myself to think that Warren’s apology and reference to an email is actually about me? That is ridiculous. I know there were others who emailed him. But for the sake of argument, let’s assume Warren is talking about my email, which I re-read. I never say “I am offended.” I had a lot of questions because I wanted to understand. I wanted to hear and open up dialogue because I didn’t understand Warren’s logic, humor, or joke. I really didn’t understand why Warren’s supporters would then try to shut down those who were offended (and I include myself in the camp of those hurt, upset, offended AND distressed) by telling us/me to be more Christian like they themselves were being.

There is no “if.” I am hurt, upset, offended, and distressed, not just because “an” image was posted, but that Warren posted the image of a Red Guard soldier as a joke, because people pointed out the disconcerting nature of posting such an image — and then Warren told us to get over it, alluded to how the self-righteous didn’t get Jesus’ jokes but Jesus’ disciples did, and then erased any proof of his public missteps and his followers’ mean-spirited comments that appeared to go unmoderated.

I am hurt, upset, offended, and distressed when fellow Christians are quick to use Matthew 18 publicly to admonish me (and others) to take this issue up privately without recognizing the irony of their actions, when fellow Christians accuse me of playing the race card without trying to understand the race card they can pretend doesn’t exist but still benefit from, when fellow Christians accuse me of having nothing better to do than attack a man of God who has done great things for the Kingdom.

Dear Pastor Rick Warren, I Think You Don’t Get It

Author's Note: As of sometime Tuesday afternoon, the original Facebook post and tweet of this image has been removed. That is wonderful news. He has also issued an apology on Dr. Sam Tsang’s blog (linked later in this post) but not on his Facebook page or Twitter because it has all been removed. However, I am leaving up my original post because deleting something doesn’t actually address the issue, and the subsequent comments by supporters were never addressed. Those supporters may think the post was removed because he got tired of the angry Asians who don’t get it. Right now, it feels like I’ve been silenced. Pastor Warren actually did read many of the comments voicing concern about the post and responded with a rather ungracious response. My kids constantly hear me talk about the consequences of posting something up on social media and the permanence of that.

You know it’s going to be an interesting day when you wake up to Facebook tags and messages about “something you would blog about.”

My dear readers, you know me too well.

This photo appeared yesterday on Rick Warren’s Facebook page and Twitter feed. Apparently the image captures “the typical attitude of Saddleback Staff as they start work each day.” Hmmm. I didn’t realize Saddleback was akin to the Red Army. Warren’s defense (and that of his supporters) is one that I AM SO SICK AND TIRED OF HEARING!