Maria J. Stephan, co-author (with Erica Chenoweth) of Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, is chief organizer of the Horizons Project, where she works to build a just, inclusive, and peaceful democracy in the U.S.

Posts By This Author

Faith and the Authoritarian Playbook

In 2012 I was a U.S. State Department officer deployed to Turkey to work with the Syrian opposition. It was an opportunity to support Syrian activists waging a remarkable popular struggle against an authoritarian government that had responded to peaceful protest with bullets and torture. For nearly a year, Syrian Sunnis, Christians, Kurds, Druze, Alawites, and others used demonstrations, sit-ins, resistance music, colorful graffiti, consumer boycotts, and dozens of other nonviolent tactics to challenge the Bashar al-Assad administration. But the nonviolent movement was unable to remain resilient in the face of brutality, external support for civil resistance was weak, and finally Syrians took up arms. This played into Assad’s hand. Death, displacement, and destruction skyrocketed. Extremists exploited the chaos. The Syrian nonviolent pro-democracy forces were inspired and courageous but lacked organization and adequate support to prepare them for the long haul. This haunts me to this day.

I’ve worked around the world with scholars, activists, policy makers, and faith communities to design effective support for nonviolent struggles to defend and advance freedom and dignity. I’ve been mentored by leaders of the U.S. civil rights movement, the greatest pro-democracy movement in our history, whose strategic campaigns to dismantle racial authoritarianism hold great relevance today.

As we head into the 2024 election, the risks to freedom and democracy are higher than they’ve been for decades. Religious communities who understand that democracy is the best modern governing system for protecting religious freedom and advancing shared values have a critical role to play as partisans for democracy.

10 Ways Christians Can Protect Democracy

Commitment to democratic norms is not a matter of political partisanship. The vast majority of Americans believe in, practice, and defend democracy — but there are partisan elites with powerful antidemocratic impulses gaining a foothold. People of faith have values rooted deeper than any political ideology and have led powerful pro-democracy movements around the world. In Hope and History, Vincent G. Harding reminds us that history, like our democracy, is not a spectacle but a task; it’s “a destiny that is still ours to create.”

Can Multiracial Democracy Survive?

DEMOCRACIES OFTEN DIE by a thousand small cuts. The slide from a robust, if unfinished, democracy to an authoritarian government is incremental and uses inherent weaknesses in a country’s institution and culture. In the U.S., racism has been a core weakness debilitating progress toward a vibrant inclusive democracy, exploited by autocrats to maintain power no matter the cost to human dignity and freedom.

Since 2015, the U.S. democracy score has slid from 92 to 83, according to Freedom House’s global index, lower than any democracy in Western Europe. At a point when pro-democracy and anti-racism movements need to be strongest in the U.S., we find them at odds.

I work in many pro-democracy coalitions committed to political and ideological pluralism where it is challenging to identify the role of white supremacy and Christian nationalism in undermining democratic norms. Conservatives see these as “leftist” issues and moderates fear dividing an already fragile coalition. I also work with political progressives who often see police brutality and mass incarceration as aberrations in a functioning democracy rather than direct attacks on democracy itself, as political scientists Vesla M. Weaver and Gwen Prowse have laid out in their analysis of racial authoritarianism and as Black intellectuals and activists have understood for decades.

Authoritarianism is a system that concentrates wealth and power in a relatively small group of unaccountable people. Authoritarian systems are made up of authoritarian leaders and their institutional enablers, including members of political parties, media outlets, businesses, and religious institutions who provide autocrats with critical sources of social, political, economic, and financial power. Authoritarian systems engage in a range of anti-democratic behaviors to consolidate or expand power, such as weaponizing disinformation, gutting institutional checks on power, subverting free and fair elections, undermining civil liberties, and condoning political violence.

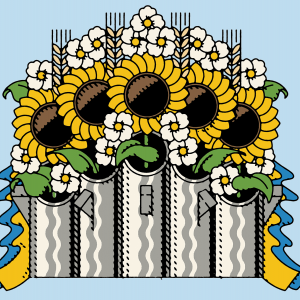

In Ukraine, Civil Resistance is Led by Unarmed Civilians

VLADIMIR PUTIN'S BRUTAL military intervention into Ukraine, and the Ukrainian people’s courageous stand in defense of democracy, human rights, and human dignity, will go down as one of the most consequential events of the early 21st century. While we mourn the tragic loss of life and growing humanitarian crisis caused by Putin’s invasion, the global community has an opportunity to double down on its support for civil resisters and peacebuilders in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus while massively increasing investment in nonmilitary approaches to challenging war and tyranny around the world, including in the United States.

Sadly, I’m quite familiar with Putin’s authoritarian playbook. In 2001, I worked with a Russian human rights organization that focused on atrocities committed by Russian forces in Chechnya. At the U.S. State Department 11 years later, my work had turned to Syria when Putin backed the Assad regime in dropping barrel bombs and using chemical weapons against the Syrian people. Putin’s scorched-earth tactics and his willingness to target civilians are all too familiar, but no less despicable.

Why Today’s Protests Are Easier to Start…and Less Successful

IN LESS THAN two weeks in late 2019, three heads of government (in Iraq, Lebanon, and Bolivia) agreed to step down under pressure from mass protests. Earlier last year, long-standing military dictators in Sudan and Algeria were forced from power following popular uprisings.

On their own, these events are remarkable. What makes them truly extraordinary is that they came amid a worldwide protest wave from Hong Kong to Manipur to Chile that has toppled governments, led to new social policies, and challenged basic economic structures.

Authoritarian regimes are not protesters’ only targets. In Chile, considered an oasis of stability in South America, protests triggered by a hike in subway fares have grown into popular demands for an end to corruption and economic inequality. And the global climate movement has used walkouts, sit-ins, and civil disobedience to dramatize the need for urgent action. In each case, popular dissatisfaction with traditional institutional approaches has encouraged a turn to extra-institutional (and at times extra-legal) resistance.

Surprisingly, this proliferation of people-power movements has taken place amid a period of declining effectiveness for movements. While around 70 percent of major nonviolent movements in the 1990s succeeded, only around 30 percent did so from 2010 to 2017. Protests have been easier to start but more difficult to resolve. So, have the movements of 2019 broken these trends?

We link the declining rates of effectiveness and their potential reversal to the emergence of parallel global networks of protesters and repressive governments (both dictatorships and democracies), who use increasing access to global information to rapidly learn from one another. This means that ideas, symbols, and tactics that both help movements succeed and successfully suppress them spread quickly from their origins to other struggles. In the past, waves of successful protests often lasted years. What we are seeing now—and are likely to see more of in the future—are short, sharp waves of successful protests followed by short waves of failures.

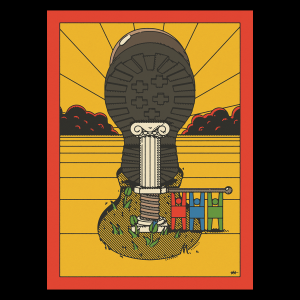

The Price of Freedom

AUTHORITARIANISM is on the march. The rise of right-wing populism in Hungary, Poland, the Philippines, and now the United States highlights the fragility of democracy. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban has propagated anti-immigrant sentiment while cracking down on independent media. Poland’s nationalist party has challenged judicial independence while asserting state control over media. Philippine’s President Rodrigo Duterte has vowed to strip civil liberties and employ violent vigilantism to address drug problems. In the U.S., Donald Trump mobilized a largely white base while railing against societal groups, including Muslims and immigrants, to win the election.

Authoritarian figures elected in democratic contexts often ignore constitutions, gut institutions, consolidate power, and snuff out domestic dissent. Dictators are often vindictive; they put themselves above the law and thrive on fear and popular apathy. Their toolkit includes ridiculing and delegitimizing protesters, pitting societal groups against each other, and coopting potential challengers.

But authoritarian figures have an Achilles’ heel. To stay in power, they depend on the obedience and cooperation of ordinary people. If and when large numbers of people from key sectors of society (workers, bureaucrats, students, business leaders, police) stop giving their skills and resources to the ruler, he or she can no longer rule.

Historically, the most powerful antidote to authoritarian figures has been strategic organizing and collective action. That includes civil resistance, employing tactics such as marches, consumer boycotts, labor strikes, go-slow tactics, and demonstrations. In democracies, civil resistance has often been used alongside institutional approaches (elections, legislation, court cases) to defend and advance political and economic rights.

How Can We Help the Nonviolent Struggle in Syria?

Image via wong yu liang / Shutterstock

Three years ago, I was a U.S. State Department officer deployed to Turkey to work with the Syrian opposition. It was an amazing opportunity to support Syrian activists and civic leaders waging an improbable — yet remarkable — popular struggle, against a criminal regime that responded to peaceful protests with bullets and torture. For [the previous] eight months since the start of the revolution in March 2011, Syrian activists — Sunni, Christian, Kurdish, Druze, and Alawite — had used demonstrations, sit-ins, resistance music, colorful graffiti, online satire, and dozens of other nonviolent tactics to challenge the Assad regime. My task, along with that of my U.S. government and international colleagues, was to aid their efforts.

A year earlier, I co-wrote and published a book with Erica Chenoweth, called Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. In it, we tested the conventional wisdom that only violence works against formidable foes like dictatorships and foreign military occupations. In studying 323 violent and nonviolent campaigns from 1900-2006, Erica and I found that nonviolent civil resistance was twice as successful as armed struggle — even against militarily superior opponents willing to use violence. We also found that nonviolent struggle helps consolidate democracy and civil peace.

Resisting ISIS

Image via Flickr / Aram Tahhan / CC BY-NC 2.0

IN JULY 2013 in Raqqa, the first city liberated from regime control in northeastern Syria, a Muslim schoolteacher named Soaad Nofal marched daily to ISIS headquarters. She carried a cardboard sign with messages challenging the behaviors of members of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria as un-Islamic after the kidnapping of nonviolent activists. After Nofal was joined by hundreds of other protesters, a small number of activists were released. It is a small achievement, but an indication of what communities supported in responsible ways from the outside could achieve on a larger scale in areas controlled or threatened by ISIS.

In the fight against ISIS, unarmed civilians would seem to be powerless. How can collective nonviolent action stand a chance against a heavily armed, well-financed, and highly organized extremist group that engages in public beheadings, kidnappings, and forced recruitment of child soldiers and sex slaves? One whose ideology sanctions the killing of “infidels” and the creation of a caliphate?

Libya's Revolution: A Model for the Region?

Recent analyses of the Arab Spring have questioned the efficacy of nonviolent resistance compared to armed struggle in ousting authoritarian regimes. The relatively expeditious victories of the nonviolent uprisings (not "revolutions," as some suggest) in Tunisia and Egypt stand in stark contrast to Libya, where a disparate amalgam of armed groups, guided politically by the Libyan Transitional National Council (TNC) and backed militarily by NATO, are on the verge of removing Moammar Gadhafi from power. As someone who has written extensively about civil resistance, notably in the Middle East, while at the same time working on the Libya portfolio within the State Department, I've been grappling with the meaning and significance of the Libyan revolution and its possible impact on the region.

First of all, like most people, including my State Department colleagues, as well as democrats and freedom fighters around the world, I am delighted that an especially odious and delusional Libyan dictator is getting the boot. I applaud the bravery and determination of the Libyan people, who have endured four decades of a despicable dictatorship and have made great sacrifices to arrive at this point. I hail the extensive planning that my U.S. government colleagues have undertaken over the past five months, in concert with Libyan and international partners, to support a post-Gadhafi transition process.