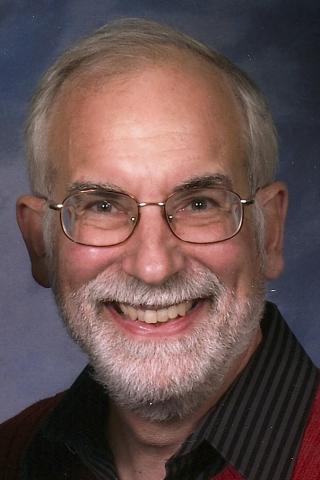

Phil Haslanger is pastor at Memorial United Church of Christ in Fitchburg, Wisconsin. He spent most of his adult life working as a journalist for The Capital Times in Madison, Wisconsin, and he still writes a monthly column there on the intersection of faith and politics.

His life has straddled those worlds of religion and politics for a long time and Sojourners has been a source of both inspiration and challenge to him over the decades. As a journalist, he served as president of the National Conference of Editorial Writers (now the Association of Opinion Journalists) in 2002 and is currently a board member for the Religion News Service.

He was ordained in the United Church of Christ in 2007 and is active in state and regional denominational activities. In the Madison area, he has been particularly active in interfaith work, interracial work and mobilizing faith communities around issues of domestic violence.

He is married to Ellen Reuter, a spiritual director and artist, and he has four grown children scattered from coast to coast.

Posts By This Author

A Woman and a Judge

It is not just in the courtroom where women are not always believed. If you have been following the news over the last few weeks, you have seen and heard and read about so many vivid and horrifying examples, whether it be sexual assault or domestic violence.

Let’s try to put aside the political ramifications of all this. The feelings and emotions that have been unleashed reach far beyond any single candidate. They get to the core of our lives — how we treat one another, how we stand up for those who are under assault, how we live as men and women in our society.

4 Stories at the NMAAHC That Changed How I See America

The woman in line with me had come to the National Museum of African American History and Culture came from Tulsa, Okla. — a city where both history and present reflect the realities of America.

She was an older African-American woman who knew Terence Crutcher, the 40-year old unarmed black man killed Sept. 16 by a white police officer now charged with manslaughter. The woman in line had been at his mournful prayer service the week before, then flew to Washington for the celebratory opening of this museum.

Preaching About Domestic Violence Is Hard — But We Must

Image via Josef Hanus / Shutterstock.com

It’s hard to stand in front of a congregation and talk about domestic violence.

It’s hard, because you never really know the stories of the people sitting there.

Who might have experienced domestic violence in their lives, in their home growing up, in a relationship during high school, on a college campus, in the home where they now reside?

Who might have experienced it last night? Who might have been told by their mother or religious leader that they cannot leave an abusive marriage because they would be breaking their vows? Who might have struck out at a partner? Who might have let their needs for control overwhelm their sense of self-restraint? Who might want to mask their violence with a smile or generous donations?

It's hard to stand in front of a congregation and talk about domestic violence. But it’s essential.

It’s essential because too often in the past, religious traditions have been used to defend an abusive patriarchy, to bind victims to marriage commitments that are undermined by intimate violence, to encourage people to “offer up” suffering rather than change the conditions that cause it.

It’s essential because shining a light of the reality of domestic violence is a critical step in creating pathways to safety for those who are victims. It’s essential because speaking out about domestic violence as a violation of God’s love can give victims strength to seek a better way. It’s essential because naming domestic violence as evil can help call perpetrators to account – and perhaps to repentance and treatment.

Job Knew What It's Like to Feel Trapped

Image via BortN66 / Shutterstock

The story of Job is one of the literary classics in the Bible. It is a story that tries to sort out why bad things happen to good people. It is a story that tries to make sense out of suffering. It is a story that concludes with an epic confrontation between Job and God. And it is a story that captures the isolation, the misunderstanding, and the feelings of abandonment.

Job’s friends and his wife are convinced that it is Job’s sin that has led to his misfortunes. That has a familiar ring to people trapped in violent and abusive relationships. “Why did you make him mad?” friends ask. “Why don’t you just leave?”

And inside the relationship, the abuser often threatens even greater harm if the victim tells anyone about what is happening. And if the victim decides to leave, the risk of violence increases, often with lethal consequences.

As Job said of God, “If I go forward, he is not there; or backward, I cannot perceive him; on the left he hides, and I cannot behold him; I turn to the right, but I cannot see him…If only I could vanish in darkness and thick darkness would cover my face!” (Job 23:8-9, 17)

Victims of domestic violence – both women and men as well as children – often feel isolated, abandoned by family and friends who are uncomfortable or afraid of the topic, trapped by religious traditions that stress male dominance and the indissolubility of marriage and feel forgotten by God. Job knew that feeling.

What I Learned from My Time in Solitary

I started this year in solitary confinement.

It’s not that I am regularly in prison or that I had behaved so badly. I was simply in a mock solitary cell located in the sanctuary of a church. I was only there for an hour. I knew I would be getting out.

But that hour did offer a glimpse into the world of how solitary confinement is used – and abused – in our nation’s prisons. And it offered a glimpse at the reform efforts that are gaining steam all across the country, including in my home state of Wisconsin.

When Kate Edwards, a Buddhist chaplain who has worked in the Wisconsin prison for the past five-and-half years, closed the door behind me, I was alone, but hardly in silence.

Wearing Black in Advent

On a Sunday when the dominant color in Christian churches is pink — a symbol of joy for the third Sunday of Advent — I was wearing a black shirt, black pants, and a blue tie. Others in our congregation were wearing various combinations of black or blue.

This was a modest way of showing solidarity with African Americans and a reminder that “Black Lives Matter” while still showing empathy for the police in the Madison, Wisconsin, area who have worked hard over the years to have a diverse force that works to serve rather than dominate the varied racial and ethnic communities that exist here.

But even with a nod to the pressure police are under these days, the dominant focus was on the series of killings of unarmed black people. And we know that not all police departments have made the same efforts that have happened here over a generation — and that our police departments are not perfect either.

The movement to wear black on December 14 came from several African-American denominations across the nation. Here in Wisconsin, Rev. Scott Anderson, Executive Director of the Wisconsin Council of Churches, joined faith leaders in urging people to wear black to church on that Sunday.

The Emptiness of Gun Violence

The empty shoes came in all shapes and sizes — cowboy boots and sneakers, children’s sparkly shoes and women’s dress shoes. They filled step after step going up toward the entrance of the Wisconsin State Capitol.

The shoes — 467 pair of them — represented the death toll from guns in just one state: Wisconsin.

"I want you to look at these empty shoes," Jeri Bonavia, told the crowd gathered on the Capitol steps on Monday. "I want you to bear witness. All across our state, families are aching with emptiness."

Bonavia is the executive director of the Wisconsin Anti-Violence Effort, which is using this display of empty shoes in five cities around the state this week.

In the nationwide scheme of things, Wisconsin has a lower death rate from guns than the nation as a whole. The annual average of 467 from murder, suicide and accidents is just a fraction of the approximately 30,000 gun deaths each year across the U.S.

And yet the row upon row of empty shoes on the steps spoke to the heartache that comes with each death, whatever the toll in whatever state.

On Domestic Violence, the Church Has a Long Way to Go

I thought at first that it was a fictional scene, conflating in one example some of the problems those of us in Christianity face when confronted with issues of domestic violence. The scene was set up as a call to rethink how we articulate our theology in areas like sacrifice and forgiveness and commitment and gender roles.

Here’s what I wrote in The Capital Times in Madison, Wis., that was posted on Sunday:

“A woman has been suffering physical abuse at the hands of her husband. She finally summons up the courage to talk to her pastor about it.

“His advice: First, you need to recognize that your suffering is like Jesus’ suffering. Next, you need to forgive like Jesus forgave. Then remember that you made a commitment to marry this man for life. He is the head of your family, so you need to make sure you are doing what he wants so as not to trigger his anger.

“And then an offer: Let me meet with the two of you and help you patch up your marriage.”

I described it as a fictional scenario. And then I heard this from a friend: “that was the response from my minster regarding my first husband 30 years ago ...”

I’d like to think that many pastors these days are a least a bit wiser both theologically and practically in how they deal with someone facing domestic violence. That’s reflected in a groundbreaking survey released last week by Sojourners at The Summit: World Change Through Faith & Justice.

Reframing Failure

I’ve recently been thinking a lot about failure.

Not my failures, though I suspect we could come up with a few.

No, I’ve thinking about Scott Walker’s failed governorship in Wisconsin.

And Barack Obama’s failed presidency in the nation.

And our failed foreign policy.

And the failed Affordable Care Act.

And Walker’s failed jobs policy for the Badger State. And so on.

Then I started thinking about the failure of our political dialogue these days.

Capital Punishment and the Power of Art

The botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma on Tuesday has refocused the nation on the inherent contradictions in the death penalty. But here in Wisconsin last week, an opera helped focus the attention of one community on the many human issues woven into the debate over crime and punishment.

In real life at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, a mix of lethal drugs injected into the body of Lockett caused seizures rather than immediate death. On stage in the opera version of Dead Man Walking, the drug machine clicks, hums, and whirrs with efficiency, leaving the fictional character Joe DerRocher dead on the stage.

Dead Man Walking — the book by Sr. Helen Prejean about her work with prisoners on death row and the families of their victims — became an award-winning movie in the mid-1990s starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn. It was recreated as an opera in 2000 and since then has played in 40 cities.

What happened in Madison, Wis., last week was more than the presentation of an opera. It was the culmination of six weeks of some 20 events engaging about 1,500 community members in discussion of many facets of the criminal justice system. The two performances of the opera itself drew about 3,000 people. It was a classic example of art engaging life.

Capital punishment itself is not so much of an issue in Wisconsin – the state has banned it since 1853. But Wisconsin does have the highest rate of black male incarceration in the nation. Its prison system tilts far more toward punishment than toward treatment and rehabilitation. It imprisons twice as many people as its neighboring and demographically similar state of Minnesota.

Can We Be a Society of Second Chances?

For most folks, these names will not mean much: Eric Pizer, Christopher Barber, and Andrew Harris.

They are names that may have a bit resonance in Wisconsin, where I am from. What they represent, though, are the struggles we face as a society dealing with concepts of repentance and redemption. They represent the way those concepts get overrun by politicians seeking to exploit the public’s fears. We as a people, after all, do not seem to be in a very forgiving mood these days.

So the distinctive stories of these three Wisconsin residents might offer a good starting point for Christians thinking about what our faith tradition calls us to during this season of Lent.

Creating a Port in a Storm of Domestic Violence

I had a chance to play the role of Bad Pastor Phil last week.

The occasion was a conference at St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, Wis. called “Your Congregation: A Port in the Storm for a Victim of Domestic Violence.” Bad Pastor Phil did not provide a very good port in the storm.

The group of people from some 25 parishes and congregations in the greater Madison area had just witnessed a squirm-inducing scene where Sam came home from work the day after he had hit his wife, Mary. She had prepared his favorite meal, hoping she could make him happy.

Nothing could make Sam happy, of course, other than feeling that he was totally in control of Mary. So he demeaned her, ordered her around, threw the drink of imaginary Scotch and water she had prepared for him across the room, and finally stomped out of the house.

Sam was played by Darald Hanusa of the Midwest Domestic Violence Resource Center, a social work therapist with three decades of experience treating men who batter women. Mary was played by Terry Hoffman, who earlier in the day told a gripping story of the real-life abuse she experienced at the hands of her now former husband.

So now Sam and Mary were on their way to see their pastor. We have a problem communicating, they told me. Sam said it was all Mary’s fault. Mary tried to explain that she was trying to do the best she could, but I asked her what she was doing that was pushing Sam’s anger buttons. She tried to reply, but I kept turning the conversation back to Sam.

I reminded Mary that in the New Testament of the Bible, there were two letters from Paul that said a wife should be submissive to her husband. I ignored the fear that was all over her face.

I was acting out the role that all too often churches have played in real life. Perhaps they are not as crude as I portrayed it, but getting faith-based communities to focus on domestic violence is a growing theme these days.

Syria: It Will Take More Than Saying No to Military Strikes

There’s a catch phrase that comes to the fore when people start looking for religious reasons not to enter a war like the one now raging in Syria: “Who would Jesus bomb?”

Jesus would not have bombed anyone, of course. Bombs were not weapons of choice in his day. But the cruelty of war was no stranger to his era. The Romans could be every bit as cruel as Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. They executed dissidents like Jesus himself with ease. They leveled the city of Jerusalem.

But if it is hard to imagine Jesus targeting a cruise missile aimed at another nation, it is not hard to imaging him encouraging his followers to stand with those who are most vulnerable, to seek ways to defend others from cruelty, to come to the aid of those refugees displaced by war. The question is how best to do that.

Overcoming Stereotypes

I was in my office on a quiet afternoon when I saw the car pull into the parking lot.

Those of us who work in churches are familiar with people stopping by seeking a bit of financial help. But people stop by churches for lots of reasons. It’s best to wait to see what they want before making assumptions.

As I watched the African-American gentlemen get out of his car, I sighed. My peaceful afternoon was going to be interrupted by yet another request for help. We could do that, but it would take some time. He came into the church and I greeted him.

“Hi, how are you?”

“Fine,” he said. “But I think I’m lost. I’ve got this appointment at a business near here, but I think I missed a turn. Can you help me figure out where it is?”

So why did I assume he was looking for a handout? The only variable was the color of his skin. And in that moment, I realized how quickly I make judgments about people based on stereotypes that lurk within me. And I was grateful that I had kept that stereotype to myself when I greeted the man.

'God is Good. God is Great. Hope is Eternal:' Lessons in Life and Dying

My friend Mike died last week.

We were the same age. We grew up together in Marinette in northeast Wisconsin. Worked our way through Boy Scouts together. Played at each other’s houses. Studied in the same classrooms. And then, over time, we drifted apart. Until this past year. That’s when I learned that Mike was dying of cancer.

In less than 12 months, we re-established a friendship and Mike and his wife, Nancy, taught me amazing lessons about living with the prospect of dying.

In our initial contacts, Nancy wrote of Mike:

“He is doing well with his treatments. I am amazed, each day, how well he handles this journey we are on. Never once have we asked ‘why us?’ We feel so blessed that we have each day to love each other and enjoy our retirement one day at a time. Not everyone is so lucky to have a long goodbye with the one they love.“

An Invocation for May Day

Editor's Note: The following is the text of an invocation being given at the May Day Rally in Madison, Wis.

When we gather at a place like our State Capitol, there are people here from all sorts of religious and non-religious backgrounds.

There are Christians and Jews, Muslims and Buddhists, Hindus and and Bahai, Humanists and people who are pretty sure they believe something, but don’t know exactly how the heck to describe it.

What connects us all this day is a spirit of hospitality, a spirit of compassion and a spirit of justice.

At their worst, religious and other beliefs can isolate us in little camps where we see outsiders as threats. At their best, they call us to hospitality, not only to those we know, but to the strangers in our midst – those who come from other places, speak other languages, seek a new life. At their best, they call us to embrace those who seek to be part of our community.

Green Pastures and Valleys of Death

Last week was on in which what God envisions for our world seemed so very, very far away.

We watched in horror last Monday as two bombs exploded at the finish line of the Boston Marathon. We wept as we heard about the death of an 8-year-old boy, a 23-year-old grad student, a 29-year-old restaurant manager. We shuddered as we thought about the 170 people injured in the bombings, many of them losing feet or legs. We asked why. Why did this happen? How could human beings do this to others?

Tuesday, we learned about poisoned letters being sent to elected officials. Real poison, not just the poisonous words that are so much of our political dialogue. Is this really what God envisioned for us?

Churches Must Step Up to Help Abused Spouses

A caller into a Christian radio station was telling the hosts about some of the strains in her marriage. Soon, she was talking about the physical abuse she was receiving from her husband.

And the response of the hosts of this Christian radio show? “What are you doing that is making him so mad?”

There’s a sad history in too many Christian churches of pastors telling abused wives that their duty is, as one author noted, “to trust that God would honor her action by either stopping the abuse or giving her the strength to endure it.”

I don’t think that view is as common in churches as it once was. And in many churches pastors and other faith leaders will act thoughtfully and quickly to come to the aid of a victim of abuse. But the undercurrent of tolerating abuse lingers.

A renowned theology professor from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Bruce Ware, preached a few years ago that when women refuse to submit to their husbands, men will sometimes respond with abuse. He did not condone that, but he seemed to accept it as inevitable.

Drones Are Corroding Our Nation's Soul

The drone operators sit at consoles on military bases around the U.S. They track their targets and when the moment is right, they send the command to fire. And then people die.

Drones have been in the news a lot over the past month as Congress has considered the nomination of John Brennan to head the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Brennan has been the chief architect of the drone policies of the Obama administration.

The constitutional questions have gotten quite a public airing, but drones raise deeper moral questions about what constraints there are on weapons of war.

Yes, drones are efficient, effective, and economical. But what do they do to the soul of this nation, to the psyches of those who push the buttons from half a world away? If they are moral for the U.S. to use at will in any nation of the world, are they moral for other nations to use against us?

War on Workers

WITH A ONE-TWO punch, 2012 was bracketed by the speedy and unexpected adoption of so-called "right-to-work" laws to undermine labor unions in two Midwestern states—Indiana and Michigan. That was preceded in 2011 by other bad news for labor: frontal assaults on public employee unions in Wisconsin and in Ohio. The assault in Wisconsin succeeded despite the political firestorm it generated, but Ohio voters overrode the efforts of their governor and legislators to gut public-employee bargaining rights.

Yes, the labor wars are on full force in the Midwest—and they are challenging faith communities to dig back into their teachings about the dignity of work, the rights of workers, and the pursuit of justice.

Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, retired auxiliary bishop of the Catholic archdiocese of Detroit, minced no words in his article for the Kalamazoo Gazette in mid-December. "Right-to-work laws go against everything we believe," he wrote. "At the core of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and all great religions are the values of dignity and respect, values from which economic justice and the right to organize can never be separated."

The phrase "right to work" sounds noble, but these laws are not about guaranteeing anyone meaningful employment. Instead, they prohibit union contracts with employers from requiring non-union employees—who benefit from the union's work negotiating wages and benefits—to pay dues in recognition of that fact.