Walter Brueggemann, a Sojourners contributing editor, is professor emeritus at Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia.

Posts By This Author

Called to a Dangerous Oddness

THE PROPHETS CAN only be understood if you understand that their context is an ideological “totalism” that intends to contain all thinkable, imaginable, doable social possibilities. That totalism always wants to monopolize imagination and technology so that there seem to be no serious alternatives.

In the ancient world of the Bible, that totalism is represented and embodied by the monarchy of Solomon in the Jerusalem temple. The king was surrounded by priests in the temple and by scribes who did the fine print to legitimate everything. And that totalism was completely intolerant of any alternative thinking.

We are able, in the Old Testament, to identify many of the features of Solomon’s totalism. First of all, it was an economy of extraction that regularly transferred wealth from subsistence farmers to the elite in Jerusalem, who lived off the surplus, and the device and strategy for that extraction was an exploitative tax system.

That totalism also needs a strong military. Solomon was an arms dealer. Partly, Solomon’s military was for show, and partly it was for intimidation. The totalism also had to exercise enormous economic opulence to impress people with wealth, so that Solomon’s temple is essentially an exhibit of Solomon’s much, much gold. The temple, and the priests who operated the temple, fashioned a series of purity laws to determine who the purer people and the impurer people were, to determine who had access and who was excluded from the goodies.

The three-chambered temple of King Solomon is a lot like a commercial airline. There was the outer court for women and gentiles. There was the inner court for guys in suits. And there was the holy of holies where only the high priests could go. And that’s a lot like the tourist cabin and the first-class cabin and the cockpit where only the high priests can go. Everything is delineated by rank, and therefore by opportunities that come with it. And this whole enterprise of extraction and exhibit and grandiose commoditization was all blessed by a very anemic God, whose only function was to bless the regime. So that under Solomon, you get a chosen king, a chosen city, and a chosen land, to the exclusion of all those who were not chosen.

What you can see in the biblical record is that this totalism was completely impatient with and intolerant of any alternative thinking. It was prepared to crush any alternative thinking, which was represented by the prophets.

What you get is the expulsion of the prophets, or the killing of the prophets, because they challenge the totalism that was legitimated by this anemic God.

Eruptions of Poetry

IN THE WAY the history of the Old Testament works, for 400 years you get a recital of the kings of the family of Solomon, and these are the point persons for the extraction system. But when you read along in First and Second Kings, what you see periodically are eruptions of poetry. These are the prophets who come from nowhere. They regularly unsettle the kings, and they come to occupy space in the historical recital. You can see first of all that those prophets are without a pedigree. They don’t have any credentials that legitimate what they want to say. Second, they come from nowhere. They are people who do not accept the truth of the totalism, and the way they articulate their coming from elsewhere is that they either say, “Thus says the Lord,” or they say “The word of the Lord came to me,” and “the Lord” becomes a kind of a signal that this is a word that will not fit or accommodate the totalism.

The prophets, moreover, were deeply grounded in the old covenantal traditions and the wisdom traditions, so they knew that there were structures and limits inherent to the way of creation that could not be violated with impunity. They have a very vigorous notion of the governance of God. But along with that sense of tradition, they have an acute sense of social reality.

The Company of the Unafraid

WHEN WE ARE contained in the world that is immediately in front of us, we will inescapably end in despair. The inventory of despair-producers is well known: The failure of public institutions; the collapse of moral consensus; the failure of political nerve; growing economic inequity; and the pervasiveness of top-down violence against the vulnerable.

The good news of the gospel is that we need not be contained within that immediate world, and “hopers” refuse to be so contained: Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen (Hebrews 11:1

From Copernicus to Kaepernick

THOMAS KUHN INTRODUCED the term “paradigm shift” into common parlance in the 1960s. New paradigms teach us to see the world differently. When we receive a new paradigm, all the data flees the old one and settles into the new. For Kuhn, the classic example of a paradigm shift is the way Copernicus’ solar-centered model of the world displaced Ptolemy’s Earth-centered theory during the European Renaissance.

I knew all of that. But when Irish poet Micheal O’Siadhail referred to Copernicus as “Copernik” in his recent release, The Five Quintets, it set me toward a new thought. “Copernik” (first name Nicolaus) sounds a lot like “Kaepernick” (first name Colin).

It followed for me that Copernik (with his solar-centered hypothesis) and Kaepernick (with his refusal to stand during the national anthem at NFL games) were up to the same thing. Both performed new paradigms. While Copernik’s is now settled theory, Kaepernick’s remains highly contested. It is, moreover, highly contested precisely because it is a new paradigm that threatens everything invested in the old paradigm.

The old paradigm, so treasured in the NFL, consists in a drama of violence, money, and sex (covered by pseudo-nationalism). It provides for rich white “owners” to stage violent struggles between mostly black players. That old paradigm requires black players to conform to the ideology of white owners who use the U.S. flag to legitimate their enormous wealth and control, as if these were somehow patriotic. And because the liturgy of sex-money-violence-nationalism has become so ordinary and routine, no one notices it—exactly how the owners prefer.

Now comes Colin Kaepernick with a new paradigm that asserts that black players are free agents who are not “owned” and who do not need to participate in, collude with, or endorse the owner’s ideology.

Walter Brueggemann: Jesus Acted Out the Alternative to Empire

The first prophetic task is to be clear on the force and illegitimacy of the totalism. And what we have to recognize is that almost all of us, conservative and liberals — almost all of us, clergy and laity — are to some extent inured in the totalism. We take it as normative. And to take that as normative is a great narcotic that makes us passive and apathetic. Becoming clear and unambiguous about the force of the totalism is a teaching point that we really have to work at.

From the Archives: May 1991

THE BOOK of Isaiah believes profoundly that God’s promises will prevail in, with, and through geopolitical reality. Note what an “unreal” long shot such a conviction is. I submit that only such a conviction can energize and authorize peacemaking. For without such a passion and certitude, we will soon or late succumb to realpolitik. Thus the root of peacemaking is a theological possibility and not a socioeconomic possibility. That is, the chance for peace rests in the trustworthiness of God and the issue of God keeping faith with God’s promises.

The text that authorizes this odd, subversive conviction has two features that are worth our noting. First, the text is poetry. It is not an argument about policy, but daring, inventive impressionistic rhetoric. Second, the text is poetry on the lips of God as a promise from God. That is, the speech of God is a beginning point for newness. The text, and every use of the text, is a political act as daring and as outrageous as was Martin Luther King Jr. when he said, “I have a dream.”

Peace is a dream that is uttered first on the lips of God, a dream that speaks against all settled political reality, an act of imagination from the throne of heaven in which we are invited to participate.

This article originally appeared in the May 1991 issue of Sojourners. Read the full article in the archives.

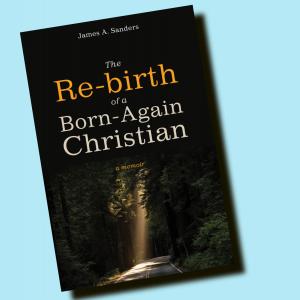

A Scholar's Faith

JIM SANDERS IS among the most respected and influential world-class Old Testament scholars of the last (my) generation. His signature interpretive impulse is what he calls a “monotheizing process.” By this Sanders means an urge toward affirmation of and obedience to the one true God, an affirmation and obedience that issues in love of the enemy in a way that requires dialogic engagement. By the term “process” Sanders insists that “monotheizing” is a dynamic, ongoing act that never reaches closure but always invites new energy and imagination. Thus, one can find in Sanders’ work both large-hearted energy and passion.

The present book is a narrative account of his life, attentive to two important themes. It traces Sanders’ maturation as a scholar with a teaching career at Colgate Rochester Divinity School, Union Theological Seminary, and Claremont School of Theology. Sanders’ great scholarly work has been his generative contribution to textual matters, with an initial focus on the Dead Sea Scrolls and then work at the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center in Claremont, Calif., where he was the key figure.

That scholarly maturation is matched in the narrative by an account of how Sanders has emerged as a powerful and insistent advocate for social justice. In his telling he grew up in South Memphis in a community that practiced racial apartheid with what he terms an “iron curtain” between whites and blacks, reinforced by an evangelicalism of the privatizing kind.

The turning point for Sanders was his college and seminary experience at Vanderbilt University. He has very little to say about his formal study in those degree programs. What counts in his memory is his involvement in campus Christian ministry programs where he came to understand the urgency of social ethics that forcefully summoned him beyond his initial evangelicalism. Led by good mentoring, he discerned the systemic practice of injustice that contradicted his newly aware sense of the gospel.

How God Intervenes

KENYATTA GILBERT: What does “being prophetic” mean to you today?

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN: I think it means to identify with some clarity and boldness the kinds of political and economic practices that contradict the purposes of God. And if they contradict the purposes of God, they will come to no good end. If you think about economic injustice or ecological abuse of the environment, it is the path of disaster. In the Old Testament they traced the path of disaster, and it seems to me that our work now is to trace the path of disaster in which we are engaged.

The amazing thing about the prophets is that they were able to pivot, after they had done that, to talk with confidence that God is working out an alternative world of well-being, of justice, of peace, of security—in spite of the contradictions.

How do we establish a sense of clarity about who we think God is in this world of radical pluralism? As long as we try to talk in terms of labels or creeds or mantras, we will never get on the same page. But if we talk about human possibility and human hurt and human suffering, then it doesn’t matter whether we’re talking with Muslims or Christians or liberals or conservatives; the irreducible reality of human hurt is undeniable.

What We Can Learn From God's Inner Conflict

Image via GaudiLab / Shutterstock.com

Hosea 11:1-11, by the force of prophetic imagination, takes us inside the troubled interiority of God. It does not, however, start there. It begins, rather, with an external encounter between God and God’s people, Israel. The poetry is cast in the imagery of “father-son,” with God cast as father and Israel cast as son. (It could as well have been cast as “mother-daughter,” but that would not happen in that ancient patriarchal society). The imagery of “father-son” was operative in Israelite imagination since God’s first declaration, “Israel is my first born son” (Exodus 4:22). Status as first-born son carries with it immense entitlement, but also inescapable responsibility to uphold the honor of the father and the family.

The Urgency of Wisdom

Image via urfin/Shutterstock.com

The present political campaign in which we are enmeshed is in many ways an exhibit of foolishness that mocks wisdom. Thus we get a great deal of careless speech. We get assaults on the poor. We get indifference to hopeless debt that is evoked by history and guaranteed by policy. We get illusions of technological fixes to relational problems, as though some technical solution can effectively assuage global warning that is grounded in unbridled greed.

We Don't Have to Let the State Define Our Identity

In this season of Lent, Isaiah 55:1-9 may be a sobering text for us. In this election season amid shrill or buoyant rhetoric, we may not notice that there are real choices to be made — even as Jews in ancient Babylon were confronted with real choices of a most elemental kind.

The Earth Awakens

stockphoto mania / Shutterstock

WHEN WE CONSIDER the crisis of climate change, many of us swing back and forth between a narrative of despair in which “there is nothing we can do” and a narrative of hope that affirms that good futures are available when we act responsibly. Surely Laudato Si’, the encyclical released by Pope Francis last spring, has given enormous impetus to the narrative of possibility, summoning us to act intentionally and systemically about climate change.

The issue of climate change is a recent one, but the matter of revivifying the creation is a very old one in faith. In ancient Israel, as now, care for creation required a vision of an alternative economy grounded in fidelity.

The economy of ancient Israel, a small economy, was controlled and administered by the socio-political elites in the capital cities of Samaria in the north and Jerusalem in the south. Those elites clustered around the king and included the priests, the scribes, the tax collectors, and no doubt other powerful people. Those urban elites extracted wealth from the small, at-risk peasant-farmers who at best lived a precarious subsistence life. The process of extraction included taxation and high interest rates on loans. These were financial arrangements that drove many of the peasants into hopeless debt so that they were rendered helpless in the economy.

While that arrangement was exploitative, it no doubt appeared, at least from an urban perspective, to be normal, because the surplus wealth and the high standard of living it made possible seemed natural and guaranteed. The power people who operated the economy could assume surplus wealth, and the exploited peasants were impotent in the face of that power. The arrangement appeared to be safe to perpetuity.

Speeches of judgment

Except that a strange thing happened in ancient Israel in the eighth century B.C.E. (750-700 B.C.E.). There appeared in Israel, inexplicably, a series of unconnected, uncredentialed poets who by their imaginative utterance disrupted that seemingly secure economic arrangement. We characteristically list in that period of Israelite history four prophets—Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, and Micah. They came from various backgrounds, but they shared a common passion and a stylized mode of evocative speech.

The “normative” economy of the period had assumed that the economy consisted of only two participants: 1) the productive peasants, and 2) the urban elites, who did not work or produce anything but who lived well off of peasant produce. Those uncredentialed poets, however, dared to imagine and to utter that there was, inescapably, a third participant in the political economy: namely, the emancipatory God of the Exodus.

Free Speech: License or Responsibility?

Image via Stuart Miles/Shutterstock

Many countries in the global community do not have the right to free speech. In the U.S., our right to speak out is protected under the Constitution. How well do we live up to the responsibility granted with that freedom?

The Epistle of James is written to urge Christians to practice the ethic of Israel’s covenantal, prophetic tradition. In this particular text, the apostle reflects on the enormous power of speech and the potential of the tongue for doing good or evil. Appeal to the covenantal, prophetic tradition of Israel may suggest two connections for us. First, the covenantal commandments of Sinai, the Ten Commandments, already have in their purview the cruciality of "right speech" — the ninth commandment prohibits "false witness."

The original reference concerns testimony in court. In larger horizon, however, the commandment pertains to the neighbor.

Facing Up to Our Broken Covenants

Lent is our season of honesty. It is a time when we may break out of our illusions to face the reality of our life in preparation for Easter, a radical new beginning.

When, through this illusion-breaking homework, we connect with reality, we see that in our society the fabric of human community is almost totally broken. One glaring evidence of such brokenness is the current unrelieved tension between police and citizens in Ferguson, Missouri.

That tension is rooted in very old racism. It also reflects the deep and growing gap between “the ownership class” that employs the police and those who have no serious access to ownership who become victims of legalized violence.

This is one frontal manifestation of “the covenant that they broke,” as referred to in the Jeremiah text for this week: a refusal of neighborly solidarity that leads, with seeming certitude, to disastrous social consequences.

Of course the issue is not limited to Ferguson but is massively systemic in U.S. society. The brokenness consists not so much in the actual street violence perpetrated in that unequal contest. The brokenness is that such brutalizing force is accepted as conventional, necessary, and routine. It is a policy and a practice of violence acted out as “ordinary” that indicates a complete failure of neighborly imagination.

Lent is a time for honesty that may disrupt the illusion of well-being that is fostered by the advocates of indulgent privilege and strident exceptionalism that disregards the facts on the ground. Against such ideological self-sufficiency, the prophetic tradition speaks of the brokenness of the covenant that makes healthy life possible.

As long as there is denial and illusion, nothing genuinely new can happen. But when reality is faced — in this case the reality of a failed covenant between legal power and vulnerable citizens — new possibility becomes imaginable.

Grief, Courage, and Perseverance

swatchandsoda / Shutterstock

[Editor's note: This article first appeared in our December 2013 issue to commemorate the one year anniversary of the Sandy Hook shooting.]

IN THE YEAR since the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., last Dec. 14, thousands more have died by gun violence, and the NRA seems to stymie sane firearm measures at every turn. How do we stave off despair, hold on to hope, and keep moving forward when the odds feel overwhelming? —The Editors

Bigger Than Politics

What do we say to those who are weary?

by Brian Doyle

WHAT WOULD I SAY to those who are weary of assault rifles mowing down children of all ages, every few months, for as long as we can remember now? Oregon Colorado Wisconsin Pennsylvania Connecticut Texas Massachusetts Minnesota Virginia do I need to go on? I would say that this is bigger than politics. I would say this is about money. I would say Isn’t it interesting that we are the biggest weapons exporter on the planet? I would say that we lie when we say children are the most important things in our society. I would say that the next time a tall oily smarmy confident beautifully suited beautifully coiffed glowing candidate for office says the words family values, someone tosses an assault rifle on the stage with a small note attached to it that reads Is this more important than a kindergarten kid?

We all are Dawn and Mary in our hearts and why we wait until hell and horror are in front of us to unleash our glorious wild defiant courage is a mystery to me.

I would also say, quietly, that this is bigger than rage and anger and snarling at idiots who pretend to hide behind the Constitution. I would say this is also about poor twisted lonely lost bent young men no one paid attention to, no one really cared about. And I would say that people like Dawn Hochsprung and Mary Scherlach, who ran right at the bent twisted kid with the rifle in Newtown, are the flash of hope and genius here. Those are the people I will celebrate on Dec. 14. There are a lot of people like Dawn Hochsprung and Mary Scherlach, may they rest in peace. We all are Dawn and Mary in our hearts and why we wait until hell and horror are in front of us to unleash our glorious wild defiant courage is a mystery to me. But it’s there. And there are a lot of days when I think the whole essence of Christianity, the actual real no kidding reason the skinny Jewish man sparked the most stunning possible revolution in history, is to gently insistently relentlessly edge us away from our savagely violent past into a future where Dawn and Mary are who we are, and you visit guns in museums, and war is a joke, and defiant peace is what we say to each other all blessed day long.

Brian Doyle is the editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland (Oregon) and the author most recently of The Thorny Grace of It, a collection of spiritual essays.

-----

An Insanity of Rationality

This spiritual disease thrives on violence and calls it good.

by Joan Chittister, OSB

THERE IS A MADNESS abroad in the land, hiding behind the Constitution, brazenly ignoring the suffering of many who, over the years, have died in its defense, and operating under the banner of rationality. It’s a rare form of spiritual disease that thrives on violence and calls it good.

They want a proper response to violence, they tell us, and, most interesting of all, they insist that only violence can control violence. If “the good guys” have guns, this argument goes, “the bad guys” won’t be able to do any harm.

The hope? The hope lies only in those who refuse to feed this addiction to violence.

This particular insanity of rationality argues that violence is an antidote to violence. Then why do we find scant proof of that anywhere? Why, for instance, hasn’t it worked in Syria, we might ask. And where was the good of it in Iraq, the land of our own misadventures, where the weapons of mass destruction we went to disarm did not even exist and the people who died in the crossfire of that insanity had not harbored bin Laden. So how much peace through violencehave all the good guys on all sides really achieved?

The insanity of rationality says it is only reasonable to arm a population to defend itself against itself. And so, day after day, the level of violence rises around us as hunting rifles and small pistols turn into larger and larger weapons of our private little wars.

Clearly this particular piece of childish logic has yet to quell the gang violence in Chicago. It didn’t even work on an army base in Texas where, we must assume, the place was loaded with legal weapons.

What’s more, it does nothing to save the lives of the good guy’s children, who pick up the good guy’s guns at the age of 2 and 3 and 4 years old and turn them on the good guy fathers who own them.

So the mayhem only increases while white men in business suits insist that their civil rights have been impugned, their right to defend themselves has been taken from them, and more guns, larger guns, insanely damaging guns are the answer. Instead of hiring more police officers, they argue that arming students and teachers themselves, nonprofessionals, will do more to maintain calm and control the damage in situations specifically designed to cause chaos than waiting for security personnel would do.

It is that kind of creeping irrationality that threatens us all.

And in the end, it is a sad commentary on our society. We have now become the most violent country in the world while our industries collapse, our educational system declines, women are denied healthcare, our infrastructure is falling apart, and there’s more money to be made selling drugs in this country than in teaching school. No wonder gun pushers fear for their lives and sell the drug that promises the security it cannot possibly give while the country is becoming more desperate for peace and security by the day.

The hope? The hope lies only in those who refuse to feed this addiction to violence. These are they who remember again that we follow the one who said “Peter, put away your sword” when it was his own life that was at stake.

The hope is you and me. Or not.

Joan Chittister, OSB, a Sojourners contributing editor, is executive director of Benetvision, author of 47 books, and co-chair of the Global Peace Initiative of Women.

How to Read the Bible

Ten books on the shelf of one of our most respected biblical scholars.

How Do We Practice an Easter Life?

These Easter readings line out the new life lived by the community of Jesus. They show, on the one hand, that Easter life is dangerous and demanding.

Good Friday: Praying in the Abyss

Photo via E. O. / Shutterstock

In Christian confession, Good Friday is the day of loss and defeat; Sunday is the day of recovery and victory. Friday and Sunday summarize the drama of the gospel that continues to be re-performed, always again, in the life of faith. In the long gospel reading of the lectionary for this week (Matthew 27:11-54), we hear the Friday element of that drama: the moment when Jesus cries out to God in abandonment (Matthew 27: 46). This reading does not carry us, for this day, toward the Sunday victory, except for the anticipatory assertion of the Roman soldier who recognized that Jesus is the power of God for new life in the world (verse 54). Given that anticipation, the reading invites the church to walk into the deep loss in hope of walking into the new life that will come at the end of the drama.

Going Public with God's Good News

Reflections on the Revised Common Lectionary, Cycle A.